Chernobyl Strawberries (31 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

I watch the small groups of white-haired men and women gather around my husband and his brother in front of the cemetery chapel. The mourners are so unmistakably English that they might have been painted by Gainsborough two centuries earlier. Fresh from their trains at Victoria and Charing Cross, they look alien and out of place, as though London is a foreign town, to be negotiated with care. Many of the men wear silk neckties with colourful regimental stripes and highly polished, thick-soled shoes which fall on the ground with a heavy parade sound. Even in retirement, they look as

though they are in uniform. âIndian Army,' whispers one experienced chapel attendant to another.

My father-in-law's long, long coffin is carried into the chapel. No one displays visible signs of grief, although it is somehow clear that the occasion is a mournful one. At a Belgrade family funeral, someone would have been wailing at this point. Other mourners would have audibly stifled their sobs in the pauses between orations, or sighed heavily against the low monotone of the Orthodox chant. Here, we open our hymn books and sing at the prompt given by the organist.

I am not familiar with the tunes and pay too much attention to the Victorian verse, which is at the same time touchingly beautiful and too upbeat about death for my taste. The celebration of departure, the refusal to accept separation as anything but a brief interlude, makes it sound as though my father-in-law is off to plant a Union flag in the sands of some paradise island. I stumble over the lines, catching up and losing the melody. I can't get myself to sing at an Anglican funeral, just as I couldn't â were it an Orthodox one â wail as my female ancestors were expected to. In Serbia old women were sometimes even paid to mourn. They walked behind the coffin in the funeral procession and celebrated the dead in wailing laments delivered in rhythmic, haunting pentameters. I am stuck somewhere between the singing and the wailing, speechless.

I am, although no one but me knows it yet, exactly one week pregnant. My father-in-law collapsed suddenly, of internal bleeding, on the night of 28 June 1999. That evening, in a sudden flash of intuition, I had announced to my husband that I wasn't going to see in my thirty-eighth birthday childless.

After thirteen years of marriage â and with only two days to go before the birthday in question â my husband knew better than to contradict, although he has always had little time for intuition of this kind. This is one of those moments in which the difference between the two worlds we come from shows most clearly. In his, destiny is something you are supposed to take into your own hands. In mine, it falls like a block of concrete from the open sky.

My father-in-law during his farming days

Is it surprising that we then try to second-guess moments of triumph and disaster by staring into the dregs of coffee at the bottom of a cup we have drunk, or at haphazardly thrown handfuls of beans, or the shoulder blades of

slaughtered animals? We deal in revelations and epiphanies in order to mask powerlessness: intimations of the future do not fully translate between my Eastern and my Western world. I am never sure whether to believe them either, but visions are the stock in trade of my Montenegrin family. One of the clans I hail from â the Prorokovic, literally the sons of prophets â throws up seers in every generation. I suspect by now that I am not one of the elect, but I often get it right none the less.

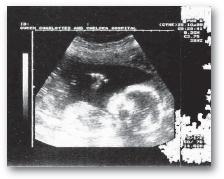

My son, Alexander, waiting to be born

I wake up in the middle of the night feeling an unfamiliar electric buzz in the pit of my stomach. âThis is it,' I say to myself. âA child.' Then the phones begin to ring, bringing the news of my father-in-law's death. In the days which follow, amid the rush of funeral arrangements, I forget about the strange, glorious moment of my son's conception, but I feel different all the time. In the cemetery chapel I know for certain that I am no longer one but two. No bigger than a tadpole by the time I turn thirty-eight, the child waits for the century to come to an end.

After the funeral service, we walk towards the cluster of Goldsworthy graves under the crowns of mature chestnut trees. One or two monuments cover empty lots, preserving the memory of men and women whose bodies lie in places like Calcutta and the Indian Ocean. The lettering has faded and we have to guess what the Victorian palimpsest adds up to. The most recent grave, built on the eve of the First World War, contains three generations of fathers, sons and their wives. For some reason, the family I married into seems always to have had four or five boys to each girl. Even in the cemetery, the world I am inscribing myself into seems overwhelmingly masculine and spartan to the core. I sit on the edge of a salmon-coloured marble square and read the rows of old-fashioned names around me: Walter, Roger, Everard, Frederick, Charlotte, Sophia, Mary Emma. I try to insert Vesna into the sequence. In 1999, this still seems an amusing thought. An eternity, uninterrupted, stretches ahead of me.

In the adjacent plot, three gleaming new black gravestones occupy what must once have been a cemetery path. Their gold Cyrillic lettering tells of Serbs exiled in London after the Second World War. One proclaims loyalty to the deposed king; one pays a tribute to Mum and Dad; the third simply marks the beginning and the end, a village in Bosnia and a suburb on the road to Heathrow Airport. I take a black scarf out of my pocket, cover my hair and say a short Orthodox prayer for the dead. Finally, the tears arrive.

For some years now, I have bidden farewell to my parents at the boarding gates of different airports, thinking, in no longer than the briefest of moments, that this hug, this kiss, this goodbye, might well be the last. I observe my father slowing down, or suddenly notice that my mother's eyes are the eyes of an old

woman, and wonder, guiltily, whether he or she will be the first to go. Although they live in a land where people grow older sooner, and die younger, so long as they are together I remain a child, and I am not sure I know how to be anything else. It is a measure of my sheltered, protected life that it never even occurs to me that the order of departure might be any different from the order of arrival.

When I am told I have cancer, it takes three days before I can make the telephone call to let Mother and Father know. I wonder whether they really need to be told. I don't know what to expect. They belong to the generation which hid this illness like a guilty secret, through mortal fear, taboo and superstition. I find out that cousins and neighbours had died from it only once I join the club myself, but I also get to hear stories of miraculous survival. I hug a ninety-year-old woman, an old family friend, feeling, for the first time, a breast that is not there. âAnd it hasn't been for over forty years,' she suddenly confides, timid but unyieldingly triumphant, like a girl.

When I finally do tell them, I cannot quite work out whether my parents are fantastically brave or in denial about what I'm going through. Their telephone calls are upbeat and full of a kind of Blitz spirit which opens no cracks for the possibility of defeat. âHow are you today, my son?' my mother asks cheerfully after each dose of chemotherapy I receive. In Serbian, calling a daughter âmy son', âmy brave son' â using the masculine as a generic name for a child â is not that unusual. With my bald, smooth head and my fresh operation scars, I look more like a son than ever before. If only she could see me. Apropos of nothing much, my shy, reticent father tells me that having me for a daughter is the best thing that has ever happened to him.

Gradually I begin to understand something about courage and denial. I decide to join the Blitz brigade myself. I

won't hide my wounds â I am too proud for that â but I shall be the brightest glow-worm in the radiotherapy department. I shall fight it wherever. I shall never surrender. You sing or wail if you like, I'll just keep mum.