Chernobyl Strawberries (30 page)

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

âNow that my daughter-in-law is a journalist,' my father-in-law says, âWould she mind taking a look at my

Piffer

column?' We are talking colleague-to-colleague here â the producer of the BBC Serbian Service to a correspondent of

The Piffer

, the newsletter of the Punjab Frontier Force, to which my father-in-law contributed a regular diary piece. It is more than half a century since he left India as part of the withdrawal of the British legions. He was still in his early twenties. After partition, in which

his

corner of India became Pakistan, there were years at Cambridge, years of active service in Malaya and Singapore, years of running a farm in Surrey and years of retirement in an ancient house in Sussex, surrounded by apple orchards, but those years somehow counted for less. The British may have left the Asian subcontinent, but my father-in-law's heart and mind were still in the rocky borderlands with Afghanistan where he served amid the ebb tide of the Raj.

As a foreigner from a poor country which was itself a kind of colony throughout most of its history, I cannot grasp the attraction of, and even less the homesickness for, India of the kind which I first encountered when I met my father-in-law. Several generations of men in my husband's family abandoned beautiful houses amid the southern English hills, which roll towards the coast like opalescent waves, for life in khaki tents on sun-blasted plateaux in Asia and Africa. Granted, there were grand army titles, and governorships of strange places, and lots

and lots of medals, or in a word â one of my father-in-law's favourite Urdu words â

izzat

(honour), but that life seems to have brought them little money and less love, and these were the only reasons, as far as I was concerned, why anyone would desire to live abroad.

Simon's great-grandfather

I had been a communist and a Tory and ended up as a typecast university lecturer: mistrustful of political parties and a leftist liberal. I vote Green to put pressure on whoever is in government, but if the Greens ever came anywhere near real power I would probably want to vote for someone else. Regardless of changes in perspective, my father-in-law's India story has never entirely made sense to me. This is perhaps because I have, in some way which is still beyond my grasp, remained an alien, even if I now understand how a love of England, her milky greenness fed by months of melancholy rain, can thrive at a distance of several thousand miles.

I scan the vast library behind my father-in-law's desk: copies of New Calcutta directories, of army lists and of what seems like just about every book on India ever published. The walls are adorned with prints of expeditions to places I didn't know existed and of wars of which I've never even heard â the battle of Goojerat, the storming of Mooltan, the battle of Sobraon. The room is a link to an earlier Britain whose pulse barely beats; but the country of which I am now part still loves its soldiers and parades, its shiny buttons and its metal toys, more than any other place in Europe, except perhaps for Serbia and Russia.

I edit his article, a list of updates from old India hands and officers' widows: illnesses, moves to old people's homes in places like Cheltenham and Chichester, and deaths, several deaths in every column. Amid all this I realize that my husband's father is now, in many ways, as much an exile in Britain as I am. We understand each other so well not because I am a journalist and journalists adore soldiers, and not because we are bound by the same name and the love of his

son, but because we both belong here and somewhere else, to places and times and countries which no longer exist. We are linked by a homesickness which doesn't make sense.

To break a long sequence of night bulletins and Balkan battles, I decide to visit the North-West Frontier Province with my husband and his father. We stay with my father-in-law's friends, retired officers of the Pakistani Army, in an Islamic version of the world of Tolstoy's novels. Martial, equestrian, latifundia-owning Pathans, they speak English and travel the world. The gulf between them and their villagers is just as great as between Bezukhov and his serfs. Among orange and mango orchards on distant country estates, I discover houses with libraries which echo my father-in-law's collection. They provide lavish shelters from the bleak villages and herds of emaciated cattle, so far removed from the dusty roads on which boys in rags play cricket after a long day's work that they might as well be in Dorset.

My father-in-law is happy, as happy as I've ever seen him be. His Urdu is rusty, his Pushto is a joke, but he is at home. In England, he often descends into long silences, but in the large households of Peshawar, Islamabad and Rawalpindi he seems never to run out of conversation. He wants to know all about government manoeuvrings, internecine Islamic clashes, reforms and road building plans, and hundreds of other details. Britain simply does not interest him any longer in this way.

He takes me to visit a hospital, a cotton factory and even a gun workshop in Tribal Territory, where the government's writ does not run and a faithful replica of any weapon you bring can be made overnight for a few rupees. My head is

covered but my mouth is not: he smiles proudly when I boast of my own prowess as a markswoman, even though I am not sure quite what I'm trying to prove.

I often have to watch him and my husband from an unaccustomed distance, seated among women in ornate

shalwar kamiz

and expensive gold jewellery. One of them quizzes me, amiably but relentlessly, about the reasons why I don't have children. She shakes her head when I say I don't know. When we bid our farewells, she whispers, âMay God give you a son next year,' into my ear.

I marvel at the beautiful century which could bring a Serbian girl, a former commie, to the verandas lining the northern edges of the Asian subcontinent in the company of an old Englishman who fought communists in the jungles of Malaya. In the long evenings, over dried mulberries and cups of sweet tea, I start to show him books I brought with me on the journey, writings by Sara Suleri, Pankaj Mishra, Anita Desai â the sort of India I know about â but he is tired after a day's walking and dozes off in the middle of my story. My husband chuckles quietly in the corner, his face hidden behind a thick history book.

I ask the servant to prepare my bed, then walk over to the room to give a helping hand. I succeed only in embarrassing the poor man. It's too late to learn how to be gracefully feudal. When I return outside, the sky is lit with hundreds of stars and for a moment the last call to prayer overpowers the crackling chimes of Big Ben on the BBC World Service, to which my father-in-law, awake again, listens in semi-darkness on my husband's small transistor radio. The news bulletin is presented by someone I know well. On the other side of the world, where the day is still unspent, I see the basement studio

of Bush House, and a freckled, serious face behind the microphone. From this distance, I feel that I too am listening to the voice of home. âI'll forgive you your wars, if you forgive mine' is something I don't say to my father-in-law. There is no need.

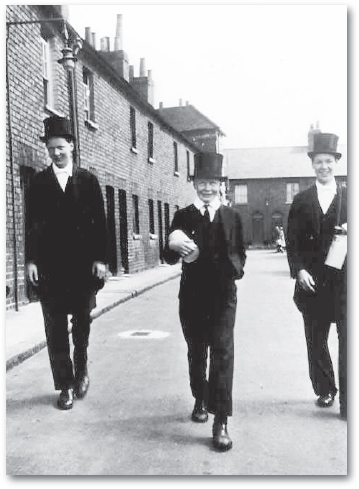

My father-in-law (tallest, as ever) with two of his brothers at Eton

THE DAY OF MY

father-in-law's funeral was one of those sunny, translucent English summer days when everything stands still for a moment. The air was full of pollen, petals and fragrance, as though someone had turned the earth â with London on it â upside down and back again, like a snowstorm in a paperweight. Even the slopes of Kensal Green cemetery, in an otherwise bleak corner of north-west London, looked so fecund and lush that it seemed as if the Victorian stone angels had gathered for a picnic on broken gravestones scattered like sugar cubes among wild flowers and tall grasses.