Chernobyl Strawberries

Read Chernobyl Strawberries Online

Authors: Vesna Goldsworthy

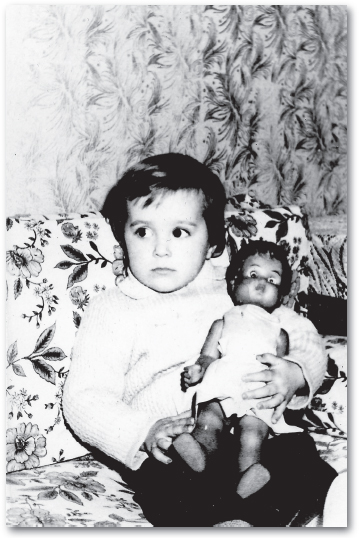

Photograph by Martin Figura

VESNA GOLDSWORTHY

was born in Belgrade in 1961 and has lived in London since 1986. She writes in English, her third language.

Chernobyl Strawberries

, first published in 2005, was serialised in

The Times

and read by Vesna herself as

Book of the Week

on BBC Radio 4. It has had fourteen editions in the German language alone.

She has written three other widely translated books:

Inventing Ruritania

(1998), on the shaping of the cultural perceptions of the Balkans; the Crashaw Prizeâwinning poetry collection,

The Angel of Salonika

(2011), one of

The Times'

s Best Poetry Books of the Year; and her debut novel

Gorsky

, the tale of a Russian oligarch in London (2015).

âA lilting, lyrical and poetic musing on Vesna's comfortable childhood, her marriage and move to Britain in the mid-1980s, cancer, and what it was like to see her country disappear â bit by bloody bit . . . a hauntingly honest account.'

Eve-Ann Prentice,

The Times

âRichly evocative.'

Gillian Reynolds,

Daily Telegraph

âThree qualities make Goldsworthy's memoir stand apart from ordinary accounts: her honesty, her skill as a writer and the fascinating circumstances of her life . . . She writes evocatively about the experience of being caught between cultures, belonging to neither, and describes how illness finally allowed her to fuse the two different personalities between which she had felt divided, one speaking Serbo-Croat, the other English . . . Chernobyl Strawberries blows away the dust; Goldsworthy writes well, often beautifully . . . Memory provides her structure. Rather than writing chronologically, she leaps back and forth in time, following threads â love, music, family, war â that send her zigzagging across her life . . . Goldsworthy's ability to find unexpected subtle connections in the pattern of her own life elevates this absorbing memoir into something extraordinary.'

Josh Lacey,

Guardian

âEngrossing . . . She writes of her dual life as a Serb and an Englishwoman with refreshing candour . . . This is, in every sense, a reflective book, the work of a fiercely honest and cultivated intelligence . . . What is remarkable here is the combination of melancholy and absurdist humour . . . But this unusual book is chiefly concerned with survival and loss â the history that led inexorably to communism, and that of the frequently complacent West â and with lasting love.'

Paul Bailey,

Sunday Times

âMany good books are travel books in one sense or another, and this one charts a more complex journey than most . . .

An exceptional memoir. If there has been a more honest, calm, and profoundly moving one written in the last few years, then I've missed it.'

Andrew Taylor,

TLS

âA charming book . . . Vesna Goldsworthy writes with wit and nostalgia about the vanished country in which she grew up . . . Beautifully written â an elegy to a world that now seems so far distant that it is difficult to remember that it began to vanish just half a generation ago.'

Victor Sebestyen,

Spectator

âHeavyweight and rewarding . . . Goldsworthy's treatment of her adopted homeland is masterly, using irony and self-deprecation to evoke affection, respect and clear-sighted criticism . . . She is equally sensitive but fair-minded as she considers her native Serbia, perpetrator of atrocities, but bombed by the country she now calls home . . . [The book is] a help to understanding the European continent's past woes and current muddles.'

The Economist

âA profound and witty memoir.'

Neal Ascherson,

Sunday Herald

âHers is a story that reaches inside you and leaves you with just a little more wisdom, a little less fear . . . Our own stereotypes of eastern Europe are cleverly excised in a book that is part a recounting of family life, part exploration of lineage and part quizzical portrait of a disappeared Europe.'

Fiona Ness,

Sunday Business Post

âA beautifully written memoir, you'll be left in no doubt about Vesna Goldsworthy's strong sense of herself, nor about her courage and her honesty . . . An uplifting but utterly unsentimental memoir of a life lived truthfully and without compromise.'

Roslyn Dee,

Sunday Tribune

Two years old

WILMINGTON SQUARE BOOKS

An imprint of Bitter Lemon Press

First published in 2005 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Reprinted in 2015 with new Foreword by

Wilmington Square Books

47 Wilmington Square

London WC1X 0ET

Copyright © 2005, 2006, 2015 Vesna Goldsworthy

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher

The moral rights of the author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-908524-48-5

9

Â

8

Â

7

Â

6

Â

5

Â

4

Â

3

Â

2

Â

1

Designed and typeset by Jane Havell Associates

For Alexander

Contents

Â

Still Life

Â

(Foreword to the 10th Anniversary Edition)

1

Â

The Beginnings, All of Them

4

Â

A Poem for Comrade Tito

5

Â

Peter the Great, Peter the Earless and Other Romances

7

Â

Homesickness, War and Radio

Â

Afterword

Â

Acknowledgements

Â

Life After

Strawberries

Â

(Epilogue to the paperback edition)

Â

My eleven favourite books

(Foreword to the 10th Anniversary Edition)

I STARTED WRITING

Chernobyl Strawberries

in the shadow of a life-threatening illness and as a record for my son, a common enough impulse for autobiographical writing. I wanted to leave an account he could read when he became old enough to feel curious about his own background, and in particular about his mother's early life in Yugoslavia, a now-vanished country. He was not yet three in the dying days of the winter of 2003, when I wrote what became the first lines of this book in English, his âfather tongue'.

The morning I started (although I did not yet know what I was embarking on), I sat at the kitchen table, staring out on a small patch of our London garden. It was easier to look at without crying than the boy who, at that same moment, was pushing a toy train in a wide circle around me. He would soon go to his nursery, and I would be left alone for a few hours. For the outside world, including family members, I maintained, for quite a while after the diagnosis, the illusion that I was working on a study of travel writing, an academic project I was researching when cancer stopped me in my tracks. I pretended, even though no one expected that of me, that some kind of momentum was being maintained, that I was carrying on as before.

I had been on sabbatical from my academic job. The long-awaited study leave indirectly â and perhaps ironically â saved my life. It freed me from teaching schedules and, in turn, left me with no excuse to continue dodging some much-postponed medical tests. I had suspected that something was wrong with my right breast for the best part of the previous year but I thought it would âgo away'. Blind optimism makes life easier. It makes death easier too.

That particular morning, I woke up soon after three a.m., thinking that I could be dead before the year was out. This was becoming a new routine. I was trying to devise a project which could keep such thoughts at bay. Tiny black birds landed on wet branches and took off, sending beads of raindrops into the air. I had no idea what type of bird I was looking at, or what species of tree. I could not name either in any of the languages I knew. I wished for a moment I could be the kind of writer who would nail a description with precision â who would write something along the lines of “a blackcap shivered on the branch of an elm” â but it seemed far too late to start learning taxonomy. What do you do with a remnant of time too long to cry your way through and too short to give any other activity much point?

I had always kept the natural world at arm's length. I was an urban creature, one of those people who stayed up all night brimming with energy in the city, and who claimed to feel morose away from noise and pollution. I once welcomed such notions of myself with humour, even smugly. They now had a new and sinister shadow, an âEt in Arcadia Ego' of cancer, which I kept trying to drive away while at the same time raking obsessively through the past in search of its beginnings. What caused it? When did it start? Any distraction, anything that threw me off of the wheel of anxiety, felt good â even confusion, sadness, or anger, so long as it was about international

politics or the defeat of a football team, so long as it had nothing to do with my body.