Born Survivors (27 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

The majority of the townspeople, however, did nothing – out of fear or ignorance. Frau Wagner said that the camp was ‘simply hushed up’. She added, ‘Most only knew that there were barracks on Hammerberg, but who was suffering in there, they didn’t want to know.’ With little outside intervention, the women’s hardship only deepened along with the winter. Even though they chose to sleep three or more to a bunk under a thin blanket, they were frozen, their feet and hands like icicles. Intense cold was hunger’s friend and the more calories they burned to keep warm, the more their bellies ached. Gradually, their bodies began to disintegrate, along with their morale.

What dispirited the women still further as they were marched through the streets each day was the sight of the Freibergers going about their ordinary business. They watched children making snowmen or leaving for school in winter coats, hats and scarves. They saw men setting off to work as their

Frauen

waved from the windows. Lisa Miková said, ‘We saw people looking at us from inside their nice warm houses. There were SS all around – about twenty of them – and it would have been impossible to communicate with us or give us food – but no one even tried. There was no interest.’

Fourteen-year-old Gerty Taussig knew by then that her parents and sister had been gassed in Auschwitz. ‘It broke your heart to see families sitting around happily in the warmth of their homes, eating and laughing and leading normal lives,’ she said. ‘No one showed us any kindness. Not a soul. We were just ghosts. None of us thought that we’d ever survive and do anything normal like that again.’

One day twenty-two-year-old German prisoner Hannelore Cohn spotted something on a morning march that made her stop in her tracks and almost trip everyone else up. Her mother, a blonde Gentile from Berlin, was standing on a street corner watching her daughter march past. One of the German

Meister

had secretly written to her family at her request to let them know that she was alive. ‘Her mother moved to Freiberg just to see Hannelore walking to the factory and back,’ said survivor Esther Bauer, who knew Hannelore for much of her life. ‘Her mother stood every morning at the gate when we came to work. They couldn’t speak to each other but at least Hannelore knew she was there,’ she said. ‘We all did.’

Gerty Taussig remembered the sight too, and added, ‘What a tragedy to stand in the street to see her emaciated daughter walking by and not even able to wave.’ Still, the mother stood on that corner every day for weeks and all those who noticed her drew comfort from her presence.

Once inside the shelter of the factory, the prisoners were able to dry out and warm up a little, although their hands throbbed painfully as they thawed. If rain or sleet was falling when they made their return march or during evening

Appell

they had nowhere to dry their clothes and no choice but to lie in them all night, shivering and wet. It was often so cold that the water froze in the tap above the trough in their communal washroom. There was one towel to share and a small piece of soap if they were lucky. They had no toothbrushes or combs and as their hair began to grow out unevenly, it itched and matted. For some, the hair grew back pure white.

As the days passed with no respite, each

Häftling

retreated into the half-life that Fate had allotted them and struggled to get

through each day. Living in separate barracks, working separate shifts often in separate buildings, Priska, Rachel and Anka still knew nothing each other. Nor were they aware of the few others also hiding their pregnancies and wondering similarly how long it would be before they were found out. A Czech friend of Lisa Miková who’d managed to hide her pregnancy unexpectedly went into labour one night. ‘She delivered her own baby in Freiberg in the barracks in February, and then the SS murdered the child,’ Lisa said. ‘The guards took the baby away and she heard later that it had been killed.’ Two more women, suspected of being pregnant also, were sent back to Auschwitz.

Their fate is unknown but their condition is unlikely to have pleased Dr Mengele, according to Czech survivor Ruth Huppert who’d been living in the Terezín ghetto with her husband around the same time as Anka. When she fell pregnant during a new round of transports at the end of 1943, she pleaded for an abortion, but the Nazis had banned the prisoner-doctors from carrying out abortions by then. Just like the three mothers in Freiberg, she was sent to Auschwitz pregnant but managed to hide it during selections. She then persuaded a

Kapo

to put her name on the list of those chosen to be sent away for slave labour.

When she had almost reached full term and was working in a German oil refinery, her pregnancy was detected and she was returned to Auschwitz in August 1944. Mengele, who demanded to know how she’d gone unnoticed, told her, ‘First you will deliver your baby, and then we’ll see.’ Within hours of her daughter being born, the ‘Angel of Death’ announced that he wanted to see how long a baby could survive without food. He commanded that the mother’s breasts be tightly bandaged to stop her feeding her child. For eight days, feverish and with her breasts swollen with milk, she and her baby lay helplessly together as Mengele visited daily. Only when the little girl was half-dead did her mother inject her with morphine given to her by a prisoner-doctor. Her child’s death saved her life and she was sent to another labour camp, eventually to survive.

The three mothers and their babies in Freiberg might well have endured a similar fate if their pregnancies had been discovered and they’d been returned to Dr Mengele. Not that there was any guarantee they would even survive Freiberg when, in the coming months, death began to claim their fellow prisoners. First, a Slovak woman in her twenties fell sick and died of sepsis after less than a month in the factory. She was buried the same day as a thirty-year-old German woman who’d died of scarlet fever. Their deaths were quickly followed by at least seven more – women and girls aged between sixteen and thirty who succumbed to pneumonia, lung, heart or other diseases. All were cremated and buried in a mass grave in the local Donat cemetery.

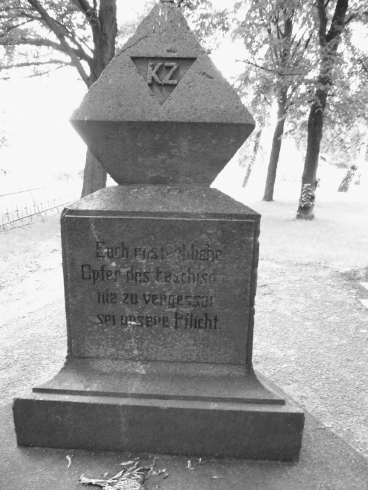

The memorial to the dead of KZ Freiberg

Priska, as tired and hungry as the rest of the inmates, stubbornly refused to allow thoughts of death to enter her mind. Still pinning her hopes on Tibor being alive somewhere, urging her to think only of beautiful things, she gazed intently at the intricate frost patterns on the windows of their barracks. One of the few who lifted her head each time they plodded to and from the factory, she would kick at the powdered snow to watch it sparkle or marvel at the hoarfrost that coated the trees like sugar on foggy mornings. She’d promised Tibor that she and their baby would survive, and he’d told her that was all he was living for. ‘I was just focused on my husband and baby. I didn’t try to get close to anyone …’ she said. ‘I was hoping that [Tibor] would be there when I came home.’

Morale dipped lower with an even greater drop in temperatures, however, and the women couldn’t help but feel increasingly desperate and abandoned. They were painfully aware that the long harsh winter would only make conditions more unbearable. Deprived of the most basic needs while slaving for the Nazis, the ghostlike figures lost even more weight. Their clothes and spirits threadbare, they developed festering sores from lice, bedbugs and their own inner decay. There was no space in their heads to think of anything but food and surviving another day. ‘I don’t even remember having dreams,’ Anka said. ‘It took so much to stay alive that there was no time for anything else.’

For Anka and Rachel, who’d already endured years of privation in the ghettos, their pitiful existence beyond all human reach seemed interminable. Whatever would happen to them and their unborn babies? What about Bernd and Monik? Were they even alive? Anka had Mitzka to share her burden and whisper to in the night, although she was afraid that even her knowledge of the pregnancy might be dangerous. Rachel, who worked with Bala every day and shared her bunk, hadn’t even told her or her other two sisters that she was expecting for fear that the information might put them at risk too.

Sala and Ester had been fortunate enough to be given secretarial jobs in the factory office, which meant better food and clothing and relative comfort. ‘We started off building aeroplanes but an SS officer came over to me when I was filing metal and asked me in German, “Where’s your sister?” I was always with her but I looked at him in shock because I didn’t even know that he knew we were sisters.’ He told them to follow him and they walked to the far end of the factory. ‘He kept on talking to me in German and asking me, “Do you know how to read and write?” He put the two of us in an office where all the plans were kept for how to make the aircraft, and we were safe for eight months! We were so lucky. We didn’t have to work hard; we had Sundays off and they even took us to the bunkers whenever there was a raid. It was cold in that part of the factory, though, and we used newspaper to wrap ourselves in and keep ourselves warm.’

After their day in the office Sala and Ester joined the rest of the women for the long march back to the barracks, where they were reunited with their sisters Rachel and Bala and tried to encourage each other to keep going. ‘It helped to share our troubles,’ Sala said. ‘We all did, especially when somebody was at the point of giving up. We would tell them that things would be better tomorrow. Always tomorrow.’

Even though the women were so terribly hungry all the time, they continued to invent imaginary feasts and recite recipes. A common game was to ‘invite’ friends for an elaborate meal and then talk them through the preparation and eating of the various dishes until their fanciful bellies were full. Another was to endlessly discuss the first thing they would like to eat when the war was over – the magical, mythical event simply known as ‘Afterwards’, which none could be sure would ever come. A thick slice of fresh bread smeared with butter was a firm favourite, although the younger girls often longed for something sweeter. Quality potatoes cooked in every possible way (especially fried) usually gained the highest number of votes.

Those who’d been cooked for all their lives by mothers or servants claimed that it was in Freiberg that they first learned how to prepare food, even though to hear the lists of ingredients for such extravagant meals drove them to distraction. Often it became a kind of self-defeating torture, reminding them too much of mothers and grandmothers and their comfortable lives ‘Before’, with all the scents and family rituals: the mouth-watering smell of freshly baked bread, the aroma of fresh coffee, or the smell and feel of lavender soap in their hands as they washed before each meal. When they looked down at the state of their begrimed fingers, they almost laughed.

‘All of a sudden we’d say, “Stop! We won’t speak about it!” Then half an hour later, we’d start again,’ said Lisa Miková. ‘Food was at the centre of our thinking – always. It dominated our lives. We longed for meat and dumplings and normal things like ham and bread. I used to say if I could just have potatoes and bread, I would not want for anything ever again.’

Gerty Taussig managed to find an entire raw potato one day, which she shared with her best friend. ‘We sliced it up very thin and ate it and it was the best thing I ever tasted. I told myself, “If I survive, this is all I shall eat.” It was finished far too soon.’

Aside from massive weight loss, the women’s extreme malnutrition caused all sorts of medical problems for which they received no treatment or sympathy. One day, Klara Löffová developed a painful tooth infection. ‘At first, nobody cared but a few days later one half of my face got so swollen and hard that I couldn’t see. Our

Lagerkommandant

took me to a dentist in town. I had to march ahead of him, he had a rifle with a bayonet; people looking at us thought that he’d just captured the biggest spy in the world.’ The dentist was told that as Klara was a prisoner he was only to do ‘necessary work’ and not ‘waste’ any anaesthetic on her. The SS officer wanted to watch but the dentist shooed him out, saying there wasn’t enough room for him to work. ‘I walked in, it was warm, clean and he was polite,’ said Klara. ’Tears came to my eyes and, when he asked me if it hurt that much, I truthfully said, “No, the

tears are because it has been a long time since I was treated as a human being.” He worked using [the painkiller] Novocaine and told me, if asked by the

Scharführer

, to tell him that it was very painful. I understood. He let me sit down for over an hour. I enjoyed every minute and gladly came back after a week for an unnecessary check-up.’

Such compassion was rare and most lived with the daily expectation of death. Having thought that nothing could be worse than Auschwitz, they began to realise that their time in KZ Freiberg would also be a fight for survival. ‘We were supposed to die,’ several of the women declared. ‘And we had so wanted to live!’ As the days passed without rescue, it wasn’t a question of if but when they would die. If not of starvation or at the hands of the guards, the increasing numbers of Allied bombs would surely kill them.