Born Survivors (26 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

Their daily routine continued with no variation. Filthy and smelly, with aching muscles, painful feet and teeth, most women spent their days and nights fighting their own mental battles and trying to stay alive. A few couldn’t stand their gruelling existence and they lost their minds, only to be sent away. ‘We worked like crazy, on our feet for hours with hardly any hair or clothes. We ate, we kept quiet, and we minded our own business,’ said one prisoner. ‘Whatever we had on we washed and put it on wet again. No one had time for anything else.’ Rotting from the inside, their gums bled, their parchment skin broke down, and any minor sore became potentially lethal. None of the women had periods as their bodies shut down and felt dead inside, and they didn’t have the energy for thoughts of resistance or rebellion. ‘At Freiberg we didn’t sabotage anything. We were afraid of our own shadow,’ said another prisoner. ‘We didn’t know how to fight back. If you said, “Where are you taking me and why?” you got hit over the head or they shot you. So everyone became too afraid to say anything.’

With educated but unskilled prisoners as a workforce, progress at the factory was painfully slow. So when Klara Löffová’s shift finished its first aeroplane wing at Christmas, a big fuss was made. The prisoners were promised – but never received – bonuses of soap

powder, bread or cheese if they completed a job. ‘The German workers celebrated, attached the wing to ropes from the ceiling and were ready for a good time. Suddenly, the rope tore, the wing fell down and was badly damaged,’ she said. ‘Now it was our turn to celebrate.’ Some of the women did receive small bonuses at Christmas – a slightly larger ration and the chance to ‘buy’ some celery salt – but for most it was work as normal.

On New Year’s Eve 1944, six months pregnant and still concealing her condition under her baggy dress, Anka tripped carrying a heavy metal workbench which fell on her leg, cutting it badly but fortunately not breaking the bone. ‘My immediate thought was, “My child! What will happen to my baby?” I was sent to a makeshift hospital and had my leg dressed and spent some time there. It was warm and I didn’t have to work. There was not much food but I could save my energy to heal my leg.’

Lying in the small sickbay trying to make herself look well enough not to be sent back to Auschwitz, Anka knew that being ill was not an option in a place where the only alternative to labour was death. Some of the women weren’t even aware that there was a sickbay. Others knew about it but feared it was merely a steppingstone to execution, so they avoided it and treated their own cuts, sores and illnesses in whichever way they could. Gerty Taussig said, ‘When you were sick, you worked or you died. Many people cured their skin problems with urine, which is all we had. That also helped my best friend who had impetigo and the pus was just dripping from her arm. Another time, my bunk collapsed and I fell onto my back and was paralysed for a while. No doctor came but I survived.’

Never having had time to really consider the baby growing inside her, Anka was able to focus on it in the infirmary for the first time. She couldn’t feel it kicking as she had with baby Dan, but somehow she sensed that it was still alive. Recalling her romantic nights with Bernd in their Terezín hayloft she worked out that their second child would be due at the end of April. She also began to wonder

what would happen if she – and it – survived. Unable to hide her pregnancy from Dr Mautnerová, the Czech paediatrician who cared for her, Anka began to confide her fears. ‘I had idiotic conversations with her. I said, “What will happen if the war isn’t over and my baby is born, and the Germans take it away from me to be brought up in a German family? Where will I find it?” It never occurred to me that they would kill it, or me. I discussed it often with her and she didn’t let on and was kind to me and assured me I would find it.’

Anka eventually returned to work but was put on so-called ‘easy’ duties, which involved sweeping the floors of the factory from top to bottom, including the stairs, fourteen hours a day. Although it was monotonous, she claimed it was the best possible exercise a pregnant woman could have. Still, her guards didn’t seem to notice that she was with child, or they would have almost certainly sent her back to the gas chambers.

Rachel, too, was lucky in that her boss was Czech and kind to her. ‘When he saw my belly growing he had me sitting, not standing, and checking that the rivets on the wings were OK,’ she said. ‘I lost weight but had no morning sickness … so I very much wanted to save the child. There was nothing more important.’

By January the new barracks for the Jewish workers were finally completed almost two kilometres away, on a street named Schachtweg in an area known as Hammerberg. As the mercury dropped, the women were turfed out of their warm, bug-infested beds and forced into the freezing new barracks. Arriving in the middle of a blizzard, they found their quarters on a snow-covered building site surrounded by high fences. The barracks, which smelled of unseasoned wood and cement, were unheated. Water dripped from the ceilings and down the walls, soaking the straw of the rank mattresses they were commanded to fill. Due to the lower ceilings there were only two tiers of bunks instead of the usual three, but none knew which were worse – the wet upper bunks or the damp lower ones.

The

Waschraum

was in a separate building and not operational at first, so the women could only wash themselves at an outside tap that repeatedly froze solid. They had small stoves and even a little coal to begin with, but the

Kapos

stole it to fuel the fires in their rooms, so thick ice frosted the inside of the windows every night. Other barracks for Russian, Ukrainian, Italian, Polish, French and Belgian prisoners-of-war were built in the same area and the women could occasionally spot some of these inmates at a distance through the coils of barbed wire that segregated them. A few of the men also worked in the factory as electricians and mechanics, so they were familiar faces to those whose jobs brought them into contact.

At a risk to all their lives, messages were occasionally passed via notes wrapped around stones and hurled across fences. Snatches of news about the progress of the war were swapped and even a few relationships sparked. Multilingual Priska was asked by a prisoner to translate a

billet-doux

from French into Slovak, a ‘crime’ punishable by she knew not what penalty. She undertook it gladly, though, thinking back to the love letters she and Tibor had written to each other and the wondrous moment when she’d spotted him through the wire at Auschwitz.

One day in the barracks an SS guard spotted her scribbling something onto a scrap of paper with the stub of a pencil. It was a reply for a woman who’d fallen for a Belgian. Seeing the guard bearing down on her, Priska simply screwed up the evidence and swallowed it. She received a beating for her trouble, followed by a long interrogation, but still she told them nothing.

The private German company that relied on its slave workforce to stay alive at least until the end of the war issued the prisoners with winter clothing that included stockings and black wooden clogs in which to clatter noisily to and from the factory. There weren’t enough to go round, though, so many women had to make do with the thin-soled and inappropriate shoes they’d been thrown in Auschwitz. Nor was getting clogs always the best option, as they

were usually too big or too small and caused painful blisters that never healed and became infected. Without any grip to their soles, the clogs were also treacherous on ice. And with no backs to them, they filled with water or snow and never dried out.

The wooden shoes had the additional disadvantage of resounding loudly against the granite cobblestones whenever the women marched, jarring already aching bones. To add to the dissonance, the well-shod SS guards in highly polished boots marched alongside them, urging them to keep pace as they shouted, ‘

Links! Zwei! Drei! Vier

…!’ (Left, two, three, four …). Klara Löffová said, ‘The people living along the street we walked to and from work were not too happy, even sending complaints to the factory about the noise at five in the morning. Imagine, five hundred people in wooden shoes marching on the street. It was blackout time constantly. They were not allowed to switch the lights on. Then at six o’clock the other group coming back from the night shift and noise again. And the morning hours were the only time they dared to go to bed – the RAF by that time were back on their way to England. We didn’t care, we didn’t sleep either.’

Even with new shoes, the women still wore the skimpy, peculiar items of clothing they’d been given, which by then were falling apart and were often held together by clips and string. They were mostly also without underwear or socks. If they were lucky enough to find a rag they’d wrap it around their shorn heads as a headscarf to protect them from the howling winds during their twice-daily march. Later they would use the same rag as a makeshift vest, to pad tight shoes, or to wrap around frostbitten toes. More often than not, though, the guards would snatch the scraps away.

And so the trek to and from the factory in the dark became a new torture, especially with painful feet and limbs stiff from immobility and cold. Anka said, ‘It was a long walk through the town where they kept spitting at us and calling us God knows what. And we had to walk all that without coats … or stockings or

something … It was awful.’ Survivor Chavna Livni said: ‘Every day the march through the dark town – before daylight, in total darkness – hardly anybody on the street – by and by I know each stone, every corner where the wind is especially cruel – And our way back again, again in darkness, into the ice-cold huts where there are stoves, but they are unlit.’

Once winter gripped, rain turned to snow and the frozen, starving prisoners limped exhausted through trenches of slush as fresh snowfalls coated them thickly. Alongside them their guards wore multiple layers of clothing topped with knee-length military greatcoats or capes, their rifles slung over their shoulders as they thrust gloved hands deep into their pockets.

One kind German with whom Rachel worked secretly gave her some pieces of soft white cotton cloth torn from material used to polish the aircraft wings; the corners were stamped ‘Freiberg KZ’. Someone else managed to get hold of a needle and thread, so Rachel borrowed it to fashion bras for herself and Bala. The same kind supervisor also slipped them a few extra morsels and it was he who found them some wooden shoes, as they hadn’t been issued with any. ‘His excuse was that we would cut our feet on the iron filings from the machines and they’d get infected, but we always thought it was so it would be easier for us to walk to work when it was cold and raining.’

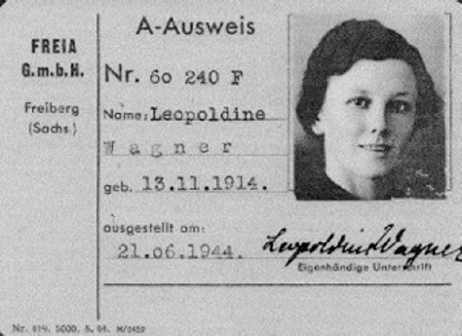

Leopoldine Wagner, an Austrian who’d been hired as an interpreter for the Italian POWs, was another employee at the factory who risked her life to help the prisoners. She said: ‘It broke your heart to see [the women] so thin, shaved, at eighteen degrees below zero without warm clothes, without socks, just in clogs … with bloody feet.’ She felt ashamed to be married to a German in the face of such misery and to see people ‘so tormented’ and ‘dog miserable’ with pus and blood oozing from their feet. After she found out that all they had to eat was ‘horrible’ turnip soup, she tried to slip a piece of bread or other food into a prisoner’s mouth whenever they came into her office to scrub the floor. One day, she gave

a bra-cum-vest to a woman who had nothing to warm her back or support her breasts.

The next day, an SS officer returned the vest to her and asked if it was hers. She nodded sheepishly. ‘If you have something to give then give it to a German,’ she was told coldly. ‘Otherwise your name will not be Frau Wagner any longer, but number one thousand and something.’

ID card of Leopoldine Wagner

Faced with such a threat, Leopoldine Wagner was almost too scared to risk helping the prisoners any more. ‘Naturally I was afraid. If a man didn’t howl with the wolf then he had one foot in the concentration camp.’ However, one day she came into contact with a teenage Hungarian Jew named Ilona, who she learned had been a pianist before the war. Bravely, she decided to try to help Ilona escape. ‘I repeatedly recited the address of my sister in Austria so that she would remember it,’ she said. ‘My idea was that she would be able to disappear into a convent.’ With the help of the local

Catholic priest, she hid a nun’s habit in the confessional of the Johanniskirche church in the centre of the old town and told Ilona to try to slip away from her guards and run there the next time she was sent for a shower at the nearby

Arbeitshaus

. ‘What became of her, I do not know. But the habit disappeared.’

Other locals such as Christa Stölzel, then aged seventeen, who worked in the factory office, also took pity on the prisoners and hid bread and cake from her lunch box in the wastepaper baskets for those who cleaned the offices to find at night. It was a crime for which there was a high penalty, but she did it repeatedly in the hope of helping the prisoners. Others too performed acts of kindness – like the foreman who would leave dressings for sores – or, on special occasions, a small bag of sweets – hidden between the struts of the aircraft wings.