Born Survivors (31 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

Some authorities alerted to the true purpose of the trains were so horrified about the ‘special freight’ being transported through their districts – especially towards the end of the war – that they refused them passage. Sadly, that often only meant that the prisoners were sent back to the hell of their camps or ‘terminated’ where their journeys were interrupted. The majority of transports, however, were allowed through.

Over the noise of the engines the railwaymen may not have been able to hear the wails of distress, the desperate cries for water from those whom they ferried, but they couldn’t have failed to hear them each time the trains stopped for an air raid, curfew or blackout, or when they had to pull into sidings to let preferential trains pass. During these numerous halts, SS guards and rail staff alike were reported to have baited those in the wagons, demanding jewels, clothing or cash in return for the water they craved – often snatching the prized item before cruelly refusing to give the donor refreshment.

Any maintenance staff working on or near the trains would have had to hold their breath against the eye-watering stench of the urine and excrement dripping from the wagons. They would have

witnessed the corpses of those who didn’t make it being thrown off at various stops. Some drivers were allegedly paid in vodka to numb their senses or help them ignore what they had become a part of. Others accepted the work for monetary gain or because they were too afraid to refuse. The trains also passed hundreds of civilians every day as they plied their way across Europe – ordinary citizens who saw, heard and smelled the trains rumble past and then watched them come back empty. Most did nothing, but there were a few who took enormous risks by alerting those further up the line so that they could be waiting to throw food, water containers, clothes or blankets into the wagons.

Others helped the many small resistance groups who were determined to stop all enemy traffic, including its most deadly trade. Despite the constant threat of torture and execution, tracks were blown up, signals, brakes and engines sabotaged, water cocks opened, coal stolen, and drivers persuaded to slow down by ambushes and derailments. Brave resistance members and partisans did much to disrupt the Nazi killing machine.

For the sick and starving women of KZ Freiberg, though, there was no such help. In snowstorms and temperatures that were to drop well below zero, they huddled together in the few centimetres of space each was allowed. ‘We couldn’t even sit on the floor all at the same time,’ said Klara Löffová. ‘There was a shortage of wagons so they crowded us in tight … April in Europe is cold, snowy, rainy – it was hellish.’ Without food or water, exposed to the weather and in pitch darkness for much of the time, they were at the mercy of the Nazis once more as their train hurtled them headlong towards what they feared was a place of no return, lurking somewhere far away in the night.

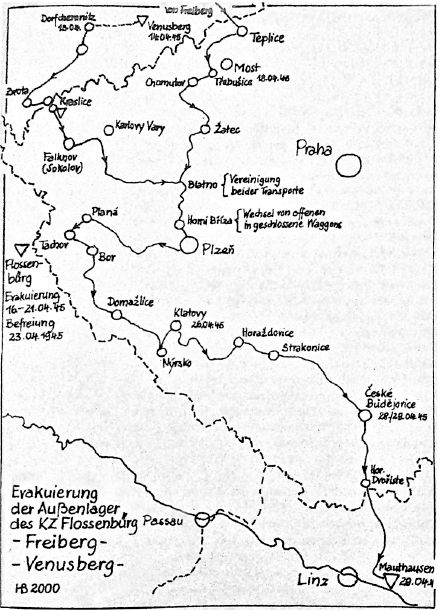

Their route south took them across the northwestern part of occupied Sudetenland and on to the Protectorate towns of Teplice-Šanov before heading for Most and Chomutov. The journey had to be constantly plotted and re-plotted by Germans directing staff from the

Böhmisch-Mährische Bahn

(Bohemian-Moravian Railway,

BMB). Along the way, points had to be hastily opened and signalmen alerted to allow the train to continue its deadly course over well-polished rails. The women were powerless in the control of those with no regard for human life, and there seemed no possible escape from an inevitable end. Tantamount to a death sentence, their lice-bitten nights turned to days then to night again, and so it went on, never coming to an end.

Map of the route from Freiberg

‘We didn’t know where we were going but we were so very afraid,’ said Lisa Miková. ‘The wagons were open and it was raining and sometimes snowing, although at least we could drink the rain or collect snow to eat … Sometimes we travelled at night as well as daytime – it depended on the air raids. It was very cold at night and that is when people often died.’

For those who still had their wits about them, the mental torment was excruciating. After all they’d been through, the daily expectation of death was more than many could stand. Had they held out for this long only to be destroyed somewhere worse, like Flossenbürg, a camp largely run by criminals? An estimated 100,000 prisoners had passed through the Flossenbürg complex and a third of them had died, including 3,500 Jews. Brutality and sexual exploitation was rampant. They had no idea that Flossenbürg had been evacuated two days after they left Freiberg and that its 16,000 surviving prisoners were forced on a death march by foot and then by cattle car to Dachau concentration camp in Germany. Approximately half perished before they reached their destination, where the majority died of starvation and exhaustion or were gassed.

With Allied planes continually flying missions, and towns and tracks bombed behind and ahead of the slow-moving train from Freiberg, mounting confusion about their destination amongst the guards and in the rail control rooms caused further delays. As they zigzagged between the two fronts, their sodden blankets clutched around them, the women waited and prayed. Gerty Taussig said, ‘We couldn’t see out. We could only see up. Overhead we watched planes fighting and Allied bombers heading for their next target but we were too weak even to wave. The guards let us out occasionally to relieve ourselves but they were always watching us closely. We tried to scratch at the grass that grew between the tracks. It was all we had to eat unless they threw some bread into our wagon, and then there’d be a big fight as everybody wanted a crumb.’

More often than not, the prisoners’ tongues and throats were so dry that, hungry as they were, they could barely eat or swallow the scraps they received. Instead they clasped the precious morsels tightly in their hands as the train pitched them from side to side. Lisa Miková said, ‘All we knew was that our route was destroyed and so we had to go somewhere else. The train kept stopping and starting and whenever we stopped they opened the doors for us to throw out the dead. We saw other transport trains almost daily – full of prisoners in striped uniforms. Some were going in our direction and some the opposite way.’

Those who were lifted up to peer gingerly over the top of their wagons were able to report when their train had crossed the border into Bohemia and Moravia because they could see Czech station names as they passed. As in the rest of occupied Europe, each town had been given a new German moniker but the original name was often still visible or only partially erased. The Czechs on board were especially overcome at the idea of being ‘home’. Survivor Hana Fischerová from Plzeň said: ‘The feelings I felt while going through our country are hard to explain … Knowing that we are home but having to go on to an unknown place from where we expect never to come home.’

Above the noise of sirens and anti-aircraft fire, they were moved to hear cries of

Nazdar!

(Hi!) or

Zůstat Naživu

! (Stay alive!) as the Czechs assured them that the war would be over soon. Their countrymen and women ran at the train to throw in food even though the guards threatened to shoot them. But their unhappy odyssey continued, which only brought fresh agony. As the train edged tentatively towards its destination, one station at a time, Anka prayed that it would turn southeast and head to Terezín. ‘That place seemed like heaven to us now,’ she said, ‘and an attainable heaven at that … but with no water, no food, no covering, and it was raining – it was unimaginable and terrible and I was in my ninth month!’

Many prisoners collapsed under the appalling conditions. Lice

plagued them day and night and all they could do was itch and scratch. Delirious with hunger, some fainted where they stood, or lay on their sides in tight configuration just as they had in Auschwitz. They’d been told to bring their bowls and spoons but that now seemed like some sort of sick joke. Their bodies were wasting away still further beneath their horribly soiled clothes and all hope was wasting away too.

Those who died were stacked in one corner in a macabre pile of white limbs until they could be dealt with. Hungry no more, their unseeing eyes stared at those who peeled the shoes from their lifeless feet before they were rolled off in places that bore no witness. Other poor wretches had death in their eyes and wouldn’t survive the next twenty-four hours. Eight women died in Gerty Taussig’s wagon in the first week. ‘At fourteen years old, all I could feel was gratitude that there was a little more space for the rest of us,’ she said. ‘There was no ceremony and not even a prayer as they were left to rot by the side of the tracks.’ In one district of the Protectorate more than a hundred corpses were discovered discarded from such transports.

Rachel said that every time the train was shunted into a marshalling yard or backed somewhere into a dead-end siding, their SS

Aufsehers

went to the nearest farm or shop and either begged for food for the prisoners or simply took what they wanted for themselves – usually eggs – which they cooked on little stoves in their own special carriages. The women could smell the eggs frying but the Nazis rarely shared any of their spoils.

Plagued more by their burning thirst than by hunger, the prisoners continually begged for water – ‘

Wasser! Bitte! Trinken!

’ – but few took any notice. To Rachel’s surprise, though, one of the SS women attached to her wagon suddenly took it upon herself to spoon-feed her water and a little food. None in the wagon could believe this sudden change of heart and all were suspicious of it, but Rachel was too weak to care. ‘She was feeding me and I was saying, “Leave me alone. I don’t have the strength.”’

And so their repugnant prison-on-wheels jerked and jolted along, moving its miserable human freight towards its inhuman destination. These once beautiful, cultured young women, many of whom had represented the cream of their societies in Europe’s finest cities, had been reduced to spectres. Crawling with vermin and reeking with the foulest odours, their teeth were falling out and their flesh had broken out in sores. None had seen their own reflections for months, if not years, but whenever they looked at the other

Häftlinge

with their split lips, hollow cheeks and hair standing up like a brush, they realised how they too must have appeared and their sense of hopelessness only deepened. ‘No food. No washing facilities. The coal dust caked and was sort of greasy and you felt not like a human at all. It was just dreadful,’ said Anka.

Whenever they stopped in a siding, regular passenger carriages passed them, along with troop trains. As the prisoners squatted shakily to relieve themselves or clung to the wagons looking around desperately for any weeds to eat, they’d see well-fed, well-dressed men, women and children gazing out at them as if they didn’t exist. To add to the cruelty, the prisoners could sometimes smell cooking from the kitchens of homes they passed – aromas of meat or bread, vegetables or fish that nearly drove them insane. They had long since abandoned the ‘torture’ of devising elaborate recipes or even talking about food. Mostly, each remained locked in their own private hell.

Lisa Miková said that with no end in sight, most people simply shut down and hardly spoke. Others talked too much and tried to keep up morale. ‘We’d ask, “What can you see?”, “Do you know something?” or “Have you heard of that place?” Each of us had terrible moments of despair but we tried to hold each other up, physically and emotionally.’ Pressed against each other without mercy, they continued their relentless journey into darkness. The train made long, unnerving halts, often for no apparent reason. At every stop the women continued to clamour for water but the dead-eyed SS officers offered none. At one stop, a few women

stumbled towards a dirty puddle but the bored guards shot at them to scare them off before ordering them back onto the train. Whenever there was an air raid, the train would stop and the SS fled or crawled under their carriage. Once again, the women prayed to be bombed, telling each other, ‘How wonderful it would be if we were hit right now! They’re right beneath us and we will crush them!’

Priska’s chief concern was to try to encourage baby Hana to feed, but her breasts were flat against her chest and there was no substance to the little milk that she had. During her pregnancy, when she should have been eating at least five hundred calories a day more than her pre-war diet, she and the other mothers had been forced to exist on between 150 and 300 calories daily with no iron or protein. And that for a body that was doing heavy labour twelve to fourteen hours a day, seven days a week, in extreme temperatures.

Somewhere further along the train, Rachel – herself weighing just seventy pounds – could no longer support the weight of her distended belly, so she lay stiff-necked and squeezed between bony carcasses on the hard floor of the open wagon. Close to her time and even closer to death, in spite of the attentions of the SS officer, she couldn’t even contemplate giving birth. Aside from her own discomfort she was greatly troubled by a woman with severe mental problems who insisted she needed to keep her swollen feet elevated. ‘She had bad legs and the only high place … was on my stomach, so she put her legs on my stomach!’ Rachel said. ‘There is no language to describe what we saw and how we lived … I sometimes think, “How did you make it?”’