Born Survivors (25 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

Once the quarantine period was over, they were finally put to work. It was two weeks since they’d left Auschwitz. The early shift was woken at 3 a.m., roll call was at 4.30 a.m., and work began at 6.30 with a short break at noon. The work wasn’t so hard in the beginning as the heavy machinery hadn’t been delivered yet. The women mostly filed down or smoothed out small components. But the days were long and tedious and morale began to plummet. ‘Everybody was depressed and we had to help each other … The worst part was no sitting down for the whole fourteen hours and not even talking.’

By the time the later transports arrived, the production line was better organised, so the new arrivals were put straight to work. ‘We were marched to a huge factory at the top of the hill where we started working forthwith …’ said Anka, who was shown how to

rivet tailfins. The machinery was heavy and difficult to hold but the factory was dry and warm, for which they were immensely grateful. ‘I hadn’t seen a riveting machine ever in my life before, and my friend neither, so you can imagine that the workmanship was beyond description … We worked fourteen hours a day, the SS kept bothering us, but there was not a gas chamber in sight and that was all that mattered.’

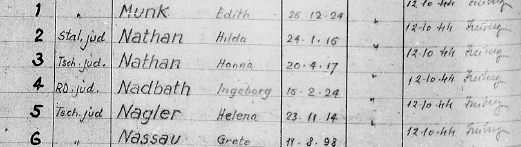

Anka’s record at Freiberg

Sala said, ‘We got a job and started making aeroplanes, and that’s why [the Germans] didn’t win the war because we made those planes!’ According to Priska, so many mistakes were made, ‘You couldn’t trust one plane that left that factory!’

The women were teamed up in pairs in the unheated work halls on the ground and first floors. Standing in ill-fitting or shredded shoes on cold concrete, they took turns to hold the pneumatic drills to use on wings that rested on metal trestles or were supported by scaffolding. Some were tasked with welding, rasping, polishing applying lacquer, while others sorted components or filed down the edges of aluminium sheets. For these largely educated professional women who’d never done manual labour in their lives, the repetitive work was physically and mentally demanding and put insufferable strain on arms, shoulders and hands, which ached day and night. In the intolerable din of pneumatic machines and drills, the air was thick with the dust from metal filings and the atmosphere toxic.

Rachel and her sister Bala were sent to work at the nearby Hildebrand factory, which ran a twenty-four-hour operation manufacturing propellers and small parts for planes. They were, she said, ‘watched like hawks’ and warned of the dire consequences of any sabotage. ‘They told us that if anything left the factory wrong, then the person working on that machine would be hung from the machine for all of us to see,’ said Rachel.

In the Freia factory there was a male SS officer in overall charge of each floor, assisted by a team of SS women some of whom were mean and some indifferent. Punishments were meted out daily and the

Häftlinge

were hit repeatedly. One guard slapped Priska hard across the cheek once for a minor matter but otherwise she was lucky. Anka, too, was hit by an SS guard who looked little older than a teenager. ‘I was pregnant and in rags with no hair, looking like nothing on earth and … she just came to me and smacked my face. It didn’t hurt. It was just totally out of context.’ Anka wanted to cry ‘very much’ at the ‘sheer injustice’ of being slapped for no offence and also for being unable to retaliate, but refused to give the guard the satisfaction. ‘It hurt me mentally more than anything I can remember of that kind.’

The civilian

Meister

or foremen who worked alongside the prisoners rarely communicated with them other than to give orders. When they did speak, many of them did so in a Saxonian dialect that was not understood even by those who spoke German. Some of these men had been in the Wehrmacht and were either too old to fight or had been sent home injured. All were keen to hang onto their comfortable jobs for the duration of the war rather than be sent to the front. ‘I don’t think they could figure out who we were and not one of them ever spoke to me or did something good for me,’ said Anka, who was paired up with her friend Mitzka. ‘No one asked … where we were from or what had happened to us. No one had any understanding at all. No one ever gave me a piece of bread or anything and they saw what we looked like and how we were treated.’

Survivor Lisa Miková had a friend who was a trained pharmacist. Her

Meister

was a man named Rausch who used sign language to communicate. One day, when she misunderstood him, the pharmacist accidentally brought him the wrong item. ‘He took it and threw it across the room and it hit the wall. Then he hit her. She had enough and said in perfect German, “If you tell me what you want then I can bring it for you.”’

Rausch looked at her in amazement. ‘You speak German?’

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘What do you think about us? We are doctors and teachers and intelligent people.’

‘We were told that you are all whores and criminals from different cities, which is why they shaved your heads.’

‘No. We are just Jews.’

‘But the Jews are black!’ cried the foreman, an opinion born of some of the wilder Nazi propaganda of the time.

After that, Rausch treated her with more respect. Not everyone else did. Some of the guards who’d heard that the prisoners weren’t whores or criminals refused to believe it. With necks that bulged over the collars of their uniforms and buttons straining not to burst, they openly mocked such claims. One ‘hunchback’ named Loffman who had graduated from Gestapo school with honours and often threw hammers at those in his charge told one woman, ‘You, a teacher? You’re a piece of dirt!’ Other guards were even more sadistic, administering beatings variously with tools, fists, belts or the end of ropes. The grumpy

Unterscharführer

known as Šára would get angry at the slightest thing and frequently struck women who annoyed him.

The female guards were often the cruellest. They not only hit the prisoners or gave them lashes but also devised punishments they knew would affect them as women. This might include forbidding them to use the toilet or commanding their friends to shave off what hair they had left, or create a stripe down the centre of their heads. One especially brutal SS officer fired her pistol to frighten the women and accidentally shot one of them in the leg, which later became infected with gangrene and began to smell.

Working their alternate shifts, the prisoners did one week of nights and then one of days, seven days a week. They had a few Sundays off which gave them a chance to rest and wash and dry their ragged clothing. Once a month, the few select prisoners who worked in the offices and therefore in closer proximity to the Germans were marched in groups to the seventeenth-century

Arbeitshaus

, a workhouse for the poor in the centre of the old town. There, they were allowed the luxury of a shower.

For all of the women, though, the work was usually so demanding and they were provided with such little nourishment that their physical decline was rapid and severe. Many fainted, which caused an unwelcome slowdown in production as a result of which they were usually beaten or kicked until they rallied. Survivor Klara Löffová said that there were two important rules: ‘You don’t admit that you are sick or that you don’t know what to do.’ Nor did they panic when the air-raid sirens went off. ‘The danger of being killed or harmed by a bomb seemed to us smaller than to be supervised by SS with guns.’ Privately, they cheered every Allied plane and scorned the ear-splitting flak from anti-aircraft weapons positioned on nearby roofs. If ever they saw a British or American plane being shot down morale would slip and ‘the rest of the day was good for nothing’.

In spite of being paid to feed their workforce, the SS gave them only the poorest-quality food and the barest minimum required for survival. One described the provisions as ‘a hot piece of dirt’. The only benefit was that they were each given a mug, bowl and spoon, which meant they no longer had to eat with hands deeply ingrained with grime. The rations were exactly the same as in Auschwitz, though – bitter black water in the morning with a piece of bread, then some suspicious-smelling soup made of beets, root vegetables or pumpkin, all of which they ate sitting on the floor or wherever they could find a space. Klara Löffová said, ‘A so-called kitchen shelled out soup; sometimes thick, sometimes watery. On long tables, no sitting down, our German

Lagerführer

, an SS man, walked

in his high boots up and down on top of the table, his belt with his SS buckle in his hand, ready to swing. The girls soon learned not to steal from someone else.’ They also learned to shield their eyes, for the loss of an eye would mean a return to Auschwitz and certain death.

In the evenings they were given 400 grams of bread and some coffee. Occasionally, they were allowed extra

Nachschub

(supplies) such as a small stick of margarine, a dollop of marmalade or a thin slice of salami. Often, they didn’t know whether to eat the margarine or use it on their dry, flaking skin. Anka said some of the women were disciplined and divided their food into portions, which they ate at intervals throughout the day. ‘I ate mine all at once and then I was hungry for twenty-four hours,’ she said.

Priska had a pregnancy craving for raw onion and would often try to exchange her entire bread ration for a segment. She was more fortunate than most because her protector Edita, who’d somehow managed to secrete some valuables, bribed one of the older Wehrmacht guards to smuggle in food. The man known as ‘Uncle Willi, The Brave’ was the only one under whose uniform there seemed to beat a human heart. He repeatedly risked his job or even his life by doing small favours for those in his charge. With his help, Edita continued to whisper, ‘Open mouth,’ to her pregnant friend and feed her a few extra morsels.

Gerty Taussig said, ‘We knew exactly who’d smuggled gold or diamonds in their private parts, because those women looked better than the majority of prisoners. But not one of us would have given their secret away.’ Even with such rare extras, the craving for food weighed heavily on the pregnant women and became their all-consuming concern. Hunger was their constant companion, along with their growing babies.

Anka never once allowed herself to consider that she wouldn’t survive, though. ‘I have been blessed with a very optimistic state of mind, which helped enormously … I always looked up and not down … I knew that I would make it, which was totally stupid and

irrational, but I lived with this idea … even though I was almost dying of hunger.’

Rachel, who also craved food, said, ‘We came home very tired and whoever could save a piece of bread would share it.’ One day, she found a slice of raw potato and sucked on it like a boiled sweet until there was nothing left. Another time she came across a mouldy cabbage half-buried in wet mud and, although she knew she could have been shot if she’d been seen picking it up, she was so hungry that she risked it. Although the cabbage stank and was so decomposed that her fingers went straight through it, she ate it whole and claimed nothing had ever tasted so good in her whole life.

In almost every spare moment the women continued to talk about food. ‘And such food!’ said Anka. ‘Not one egg or two, but ten eggs in cakes with four kilos of butter and a kilo of chocolate. It was the only way we could cope. The richer the cakes the better. It gave us some sort of satisfaction. And we devised other delights such as bananas wrapped in chocolate and then jam. It was a fantasy that helped us even though we were starving. Actually I don’t know if it helped or not, but you can’t help thinking about it because you are so hungry.’ In fact, instead of creamy cakes they had only ‘loathsome’ liquids to live on with a little bread. ‘In the end we liked everything they gave us to eat and everything was wonderful and not enough.’

When their shift ended they were finally allowed to rest on the upper floors of the factory. It was then that the women were most relieved to be working in a solid brick building instead of a draughty hut, although when they first opened the doors to the sleeping quarters they immediately smelled

Bettwanzen

– bedbugs. The SS accused the women of bringing the bugs with them but the previous inmates must have left them there. ‘The little beetles have a certain smell – sort of sweet,’ said Anka. ‘It is horrible and there were thousands of them … so many that they kept dropping from the ceiling into our mugs so whatever we ate, we ate bedbugs first.

We didn’t mind so much at first because bedbugs only live in a warm place, but if you squash them – they have a particular smell and it is dreadful.’

Without access to any news, or even to clocks, the women barely knew what day it was, and had no inkling of the dramatic events happening in the outside world. In that unventilated factory where they never saw the light of day or took in a breath of fresh air, no one bothered to enlighten them. Even the older Wehrmacht soldiers who showed occasional kindness told them little. They had no idea that the

Sonderkommando

in Auschwitz II-Birkenau had blown up Crematorium IV in October 1944, rendering it useless, but they did hear from some of the German workers that the Battle of the Bulge was raging in the Ardennes.