Born Survivors (24 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

The Freiberg factory where the women were enslaved

It was at the newly designated munitions factory in medieval Freiberg, a town in Saxony thirty-five kilometres southwest of Dresden, that the three expectant mothers were officially entered into the Nazis’ slave labour ledgers for the first time.

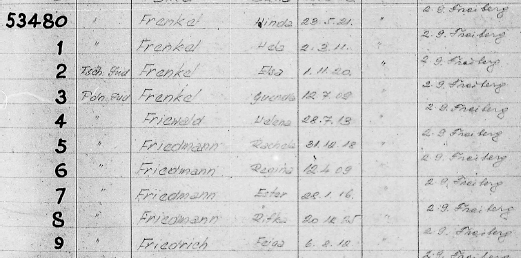

Rachel Friedman, twenty-five, listed as Polish Jew ‘Rachaela Friedmann’ (

Häftling

no. 53485), was the first of the three women to be sent to Freiberg on a train that left Auschwitz on 31 August 1944. One of 249 primarily Polish Jews, she was accompanied by her sisters Sala, Bala and Ester, still in shock after losing the rest of their family so soon after they reached Auschwitz from Łódź.

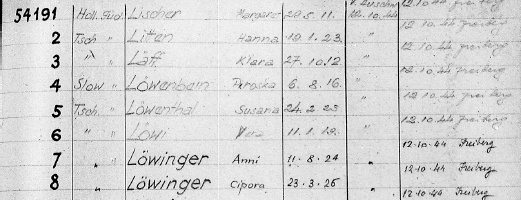

Priska Löwenbeinová, aged twenty-eight (no. 54194) and designated ‘SJ’ for Slovak Jew, arrived at KZ Freiberg on 12 October 1944. The train that brought her also carried five hundred Czech, German, Slovak, Dutch, Yugoslav, Italian, Polish, Hungarian, Russian, American and a few ‘stateless’ women. Priska’s new friend Edita, who’d assured Tibor that she would take care of his wife, was still loyally at her side. Although they didn’t know each other, Priska was on the same transport as twenty-seven-year-old Anka (no. 54243), listed as Czech Jew ‘Hanna’ Nathan, who was accompanied by her friend Mitzka and several Terezín companions.

Another transport of 251 mostly Polish Jews had left Birkenau on 22 September. All three transports were assigned consecutive prisoner numbers, which indicated meticulous coordination between the authorities at Auschwitz and those at Flossenbürg in Bavaria – the main concentration camp for the region and the one under whose control KZ Freiberg fell. Although nameless and faceless as far as the Nazis were concerned, none of the 1,001 women and teenagers aged between fourteen and fifty-five who were sent to the abandoned porcelain factory in the heart of Freiberg town underwent the ordeal of having serial numbers tattooed on their forearms. Auschwitz was the only camp in the entire Nazi system that tattooed its inmates, a practice it had begun in 1941. Those destined for the gas chambers were never registered or tattooed, which worried any who were unmarked.

‘We saw that everybody else was tattooed,’ said Anka, ‘but I never had any logical explanation [why we weren’t], unless they knew that either we would die there or all go out to work in Germany or somewhere and it wasn’t worthwhile.’

The train journey from Auschwitz took two nights and three days in closed goods wagons with little food or water. The only way they knew if it was day or night was via the chink of light through the grille of the tiny window. Leaning against each other or crouched in a corner, their legs drawn up tightly beneath them, they took turns to use the bucket with shared humiliation. Depending on which train they were on, some were fed coffee, bread and soup from a mess kitchen attached to the wagons. Others, like Anka, received nothing.

Her train finally rolled into the busy freight depot in Freiberg and disgorged its gasping cargo before its cars were hosed out and shunted back for its next payload. ‘We left our wagons half-dead, half-starved and terribly thirsty but nevertheless alive,’ Anka said. ‘We were demented with thirst. It is unimaginable … You know, the worst of the lot – choosing between hunger, cold and thirst – is thirst. All the rest is bearable but with thirst you dry out and your mouth feels like mud and the longer it lasts the worse it gets … It is indescribably awful … you would give anything for a gulp of water … And then we stopped at the station in Germany … and they gave us something to drink and that was like ambrosia – marvellous. We weren’t in Auschwitz but a civilised country.’

Dirty, dishevelled and frightened nevertheless, the women stared in hope at a clear sky free of chimneys or billowing plumes of

smoke. In wonderment, they were marched up the hill along Bahnhofstrasse through the medieval town. One survivor, fourteen-year-old Gerty Taussig from Vienna, said, ‘It was so peaceful there. No one was in the street. Somehow we had the feeling that things were going to be better. We were wrong.’ Priska said, ‘When we smelled the trees and saw the greenery in a park we passed, we were dazed.’

Priska’s record at Freiberg

Situated at the foot of the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) between Saxony and Bohemia, Freiberg had numerous ore and silver mines and an eighteenth-century university dedicated to mining and metallurgy. The only Jews left in the town were those married to Aryans, and the majority of its Gentiles worked in the mines or the optical industry. Several trains transporting

Häftlinge

to and from ghettos, concentration and labour camps had passed through Freiberg during the course of the war. Some came from Auschwitz, en route to nearby labour camps at Oederan and Hainichen, both in Saxony. Many had stopped in Freiberg to unload their human cargo, destined to slave in the mines and other industries.

Only a handful of the 35,000-strong population tried to help the unfortunate prisoners in their midst, and none of them did anything to assist the women from Auschwitz as they were herded in a ragged line through their town, a walk that took a little over thirty minutes. Rachel’s sister Sala said she almost understood why. ‘If they saw us from far away people would have thought we were from a crazy house for whores, murderers or prisoners. They were scared to look at us … we didn’t look like normal people – barefoot or in wooden shoes with strange dresses.’ Priska concurred. ‘People looked at us as if we were circus animals.’

The decision to manufacture aeroplane parts in an empty factory in the heart of Freiberg had been made in late 1943 by the Nazi government in collaboration with the armaments industry and the SS. Aside from all the planes they’d lost, many of Germany’s largest aircraft assembly plants had been bombed in a massive strategic attack known as the ‘Big Week’ at the end of February 1944.

Thousands of Allied bombs were dropped on German cities in 3,500 sorties and the massive loss of aircraft and pilots meant that air superiority over Europe passed irrevocably into Allied hands. What was left of Nazi war manufacture had to be moved to underground bunkers or to places not previously associated with warfare.

Up until that point Freiberg had never come under military attack. Then on 7 October 1944, five hundred American bombers on a mission to destroy oil refineries in the Czech industrial region of Most were hampered by low cloud and looked around for an alternative target. Spotting Freiberg with its busy railway line and sprawling factories, they dropped sixty tons of bombs that killed almost two hundred people and destroyed hundreds of homes. In less than a week, and using slave labour already incarcerated in the town, the debris was swept away and the track repaired so that the latest transport from Auschwitz could deliver Anka, Priska and almost a thousand others to their new home.

Remains of factory and living quarters

The vast stucco-fronted Freiberger Porzellanfabrik in Frauensteinerstrasse on a hill overlooking the town was built in 1906 to manufacture electrical isolators and clay industrial pipes. Owned by a company called Kahla AG, it closed in 1930 due to the economic depression and its Jewish owner Dr Werner Hofmann committed suicide after

Kristallnacht

. Having lain empty for more than a decade, the building was initially used for military storage and as temporary barracks for German soldiers. When it was decided to manufacture aeroplane parts there, the men were moved out and the women moved in.

The Arado-Flugzeugwerke company from Potsdam agreed a deal with the Reich Ministry for Armaments and War Production to produce tailfins, wheels, wings and other parts for its Arado aircraft. More specifically, components were needed for its Ar 234 plane, the world’s first jet-powered bomber, which had the reputation of being so fast and aerobatic that it was almost impossible to intercept. This plane was vital to the Nazis’

Jägerprogramm

(Hunter Programme) to try to regain control of the skies. Under the code name Freia GmbH, Arado agreed to pay the SS four Reichsmarks per day for every ‘worker’ it supplied, minus seventy

Pfennigs

a day for their ‘catering needs’. For the ‘loan’ of labour at this one factory alone, the SS could earn up to 100,000 Reichsmarks per month, the equivalent of about £30,000 today.

Most of the prisoners worked in the main factory run by Freia, but some were transferred to the nearby Hildebrand munitions factory where they made ammunition as well as precision optical parts for planes and U-boats. All were supervised by a handful of skilled German workers, as well as twenty-seven male SS guards and twenty-eight female SS-

Aufseherinnen

or prison warders. SS

Unterscharführer

(Junior Squad Leader) Richard Beck was placed in overall command of the camp and soon became known in camp code as ’Šára’ by the prisoners.

The newest inmates and the first females were among 3,000 labourers including Italian POWs as well as forced workers from

Russia, Poland, Belgium, France and Ukraine who were employed in Freiberg’s many factories or mines. The Italians were there as a punishment for their country’s ‘treacherous betrayal’ of the Reich. The so-called

Ostarbeiter

(Eastern workers), forcibly recruited from the occupied territories, were dubbed

Untermenschen

(sub-humans) by the Nazis, who treated them accordingly. There were also some

Volksdeutsche

, ethnic Germans brought back to the ‘Fatherland’ who were told they could return to their homes once their contracts ended.

Even though the war looked to be coming to a critical point as US troops reached the Siegfried Line and the Soviets gained strength, purpose-built wooden barracks were still planned for the Jewish women a kilometre and a half from the factory near the shaft of a silver mine. Until these accommodation blocks were completed, the women were billeted on the recently vacated top floor of the six-storey redbrick factory.

When Rachel arrived on the first transport the place was far from ready. There was no machinery, nor any materials to work with, so she and the other prisoners were locked into their crowded quarters and given nothing to fill the hours. Their only chance to stretch their legs was during the interminable

Appelle

that the Nazis still

insisted on, morning and night, where they stood in the foulest weather, waiting to be counted. Still, they reminded themselves, it was better than Auschwitz.

Rachel’s record at Freiberg

The sleeping arrangements were far better too; here they were two to a bunk in three tiers with up to ninety women to each room. They even had a pillow and a coverlet of sorts. There was a washroom with (infrequent) cold water and a latrine without lavatory paper. Instead they used the linings of their clothes, discarded cardboard or old newspaper – anything they could find. They were especially happy to use newsprint if it featured a photograph of Hitler.

The prisoners were told that once they started work, they would be sharing twelve- to fourteen-hour shifts so that when one group left their bunks, the next would come back to take their places. Before they could start though, an outbreak of scarlet fever meant they were quarantined for a week and the Germans established a temporary sickbay manned by forty-two-year-old Russian prisoner-doctor Alexandra Ladiejschtschikowa (a Gentile), and thirty-two-year-old Jewish Czech paediatrician Edita Mautnerová, who was later to play a significant role in the women’s lives.