Born Survivors (19 page)

Authors: Wendy Holden

Auschwitz III, at a place the Germans named Monowitz, was built in 1942 as an

Arbeitslager

or work camp specifically to provide slave labour for the German chemical company IG Farben. At Farben’s Buna Werke factory manufacturing synthetic fuel, it had a workforce of around 80,000 by 1944. Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau began taking in Jews in early 1942, the first transports coming from Bratislava and Silesia. To ease congestion, the camp was expanded with the construction of wooden blocks as far as the eye could see. Then it began accepting transports of Jews from camps such as Drancy in France and Westerbork in the Netherlands, before harvesting inmates from Terezín.

Josef Mengele arrived at Birkenau in May 1943, a member of a German contingent of medical experts in genetic and other experiments. With the devotion to duty of a workaholic, he quickly rose to a senior position. Although he was often cited as the one who carried out selections and came to represent the personification of murder for many survivors, it may not always have been Mengele

who inspected the new

Häftlinge

. What is certain is that he showed tremendous zeal for the job and appeared eager to preside over the railhead

Rampe

to ‘welcome’ as many transports as he could.

The SS officers were also given extra rations of cigarettes, soap, schnapps and food for ‘special actions’ such as the selection and execution of prisoners. These extras supplemented the generous meals prepared for them daily by chefs in the Waffen SS Club, who offered menus featuring roast chicken, baked fish, frothing tankards of beer, and unlimited quantities of ice cream and sticky desserts.

A short distance away, thousands of terrified half-starved prisoners rolled into Auschwitz every day, each of them a fresh candidate for execution. An estimated ninety per cent were murdered within hours of arrival. As soon as they had been identified as worthy of

Sonderbehandlung

or ‘Special Treatment’ (marked in the records as ‘SB’), they were sent to their deaths. In the early days, the camp was a kilometre from the railway sidings and those destined to die were transported directly to their fate in canvas-topped trucks.

The SS had tried all manner of means to kill the Jews and other enemies of the Reich, from starvation and shooting to suffocating with carbon monoxide, but these practices were largely inefficient and time-consuming, while the disposal of the bodies by burning them in trenches wasted valuable fuel. The Nazi command was keen to find a method that would eliminate large numbers simultaneously, using minimal staff and at minimum expense. Many prisoners at Auschwitz were killed by an injection of phenol to the heart, but later arrivals experienced the SS’s new preferred practice – gassing in special chambers.

At the core of Birkenau were two pretty brick cottages that had survived the destruction of the original Polish village. Known as ‘the red house’ and the ‘white house’, they were disguised as showers where the prisoners were told that they would be washed and disinfected. A lorry marked with the symbol of the Red Cross was often parked outside, an emblem of reassurance. It was, in fact, the vehicle used to transport the canisters of Zyklon B

Giftgas

(poison

gas) to those entrusted with exterminating the prisoners. An effective pesticide that had been used to control vermin in the ghettos, Zyklon B consisted of tiny crystallised pellets that released deadly hydrogen cyanide once they reacted with moisture and heat. Soviet prisoners-of-war had been the subject of merciless experiments in the basement of a prison in Auschwitz I during 1941 until Nazi doctors had fully perfected the system.

Those to be murdered were handed towels and small pieces of soap by men in white coats in an effort to further delude them, and were herded naked inside the cottages with their walled-up windows and gas-tight doors. Most had no concept of what was about to happen. The Germans would then allow several agonising minutes to pass for their body heat to warm the enclosed space. This was found to make the gas take effect far more efficiently. Only once they were huddled together in the sulphurous darkness might the sweating prisoners have begun to suspect their fate. All would have hoped for water to gush out of the false showerheads, while others hugged each other, praying, or reciting ‘

Shema Israel

’ from the Torah. When a precise amount of time had elapsed, uniformed soldiers would don gas masks, climb ladders, and empty the pellets through special vents in the roof or via openings in the walls to work with the heat and sweat to release their lethal vapour.

Foaming at the mouth or bleeding from the ears, the victims could take up to twenty minutes to die depending on how close they were to the vents. Those who administered the gas often heard them screaming, shouting and pounding on the doors as they struggled for every breath. Only when they fell silent and enough time had elapsed for the ventilation system to suck out the gas would the prisoner

Sonderkommando

(special unit) be sent in. These skilled operatives of streamlined mass destruction were forced under threat of death to dispose of the corpses. In groups of four to nine hundred men they were also known as

Geheimnisträger

, ‘bearers of secrets’. Kept in strict isolation from the rest of the prisoners, it was

their task to open the gas chambers, pull out the dead, and begin the gruesome task of washing away the faeces, vomit and blood in preparation for the next ‘batch’.

Sometimes, these prisoners came across members of their own families. Faced with such horror, several committed suicide – their only means of escape. Each unit was killed off and replaced at intervals of between three months and a year, depending on their efficiency. The first duty of any new

Sonderkommando

would be to dispose of the bodies of its predecessors. Few survived the war but, knowing their impending fate, some recorded their experiences in writing and hid the evidence to be discovered after their deaths.

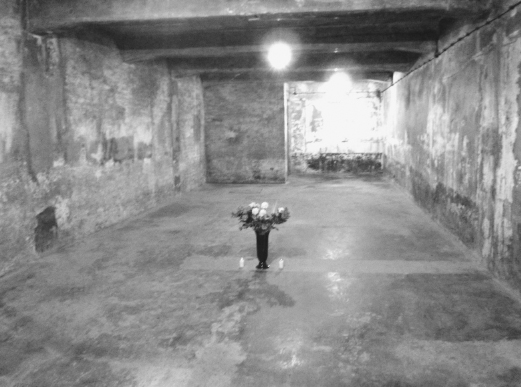

The gas chamber at Auschwitz I

The indignity both for these prisoners and for those whose corpses they handled didn’t end with their deaths. Little was wasted in the Nazi human recycling machine, where the ancillary products of

murder were salvaged for the Reich. The luxuriant curls and braided plaits of hair that had been lopped or shaved from the female prisoners’ heads were used to make cloth or netting, or as insulation and watertight padding for German war machinery. Not yet cold, every corpse would have its mouth yanked open so that teeth could be torn from jawbones with pliers, a task also undertaken by the

Sonderkommando

. A particularly fine set of teeth might be saved to make dentures. Any gems found implanted into fillings would be given to the SS ostensibly to cover the accommodation, food and transportation costs incurred in carrying out their extermination programme. Gold from teeth was melted into huge nuggets of ‘dental gold’.

Later, with deportation trains rolling in day and night, the four camp ‘

Krema

’ (crematoria) numbered II to V were specially built as extermination factories with a much greater capacity. These modern concrete edifices were a hundred metres long and fifty metres wide and contained fifteen ovens. They were not only far more efficient than the cottages but had subterranean undressing rooms that sloped straight down to the soundproof gas chambers designed to look like showers, which in turn were fitted with special electric lifts that hoisted the corpses up to the ovens once the job was done. Between them they were capable of gassing and cremating more than 4,000 people from each transport. At their peak, they gassed 8,000 men, women and children in a single day.

In the early days, the hot ashes of the dead were scattered in a series of deep ponds at the fringes of the camp, but once the water clogged with human debris, they were barrowed into a glade of silver birch trees and shovelled across the forest floor. They were also used as fertiliser in nearby fields as the area became the world’s largest Jewish graveyard. The easterly winds often caught the grey ash and sent spiralling whorls of powdered bone across the plain, which worked its gritty way into each crevice of human skin and left thick dust on every surface and on the lips. Those inmates who had somehow avoided such a fate ended up inadvertently

breathing in the charnel dust of their loved ones – day in, day out.

Priska, fresh from Bratislava, was unaware of any of this in the first few hours after her arrival at Auschwitz II-Birkenau. All she sensed in the airless, windowless shack into which she’d been locked with far too many other human beings was that she and her unborn child were in a place of the utmost danger. Mercifully, she had been reunited with Edita, who then never left her side. It was only when the women who’d been in the blocks for a while started to whisper in the dark that Priska began to comprehend how deadly it was. Veterans of almost every nationality, bald and with sunken eyes, would sidle up to the newcomers to ask if they had anything to eat. Disappointed, they would begin to tell them what went on in the camp, arguing with one another all the while. They were all condemned, claimed one ominously. They’d been brought there to die – worked or starved to death – their situation hopeless. No, they were only in quarantine, insisted another, as the different factions bickered amongst themselves. Why else had so many been sheared and some branded with tattoos? They should all pray to be selected for

Arbeit

because that was their only chance for survival, explained a third.

But where was everyone else, the newcomers asked plaintively. What about their families? Could they be in another hut, or had they been sent somewhere else to work?

‘See that?’ the skinny wretches would murmur with a twisted smile, pointing at the thickening smoke over the chimney they could see through the cracks in the walls. ‘That’s where your loved ones are – and that’s where we’ll all end up!’

The Nazis’ promises about annihilating the Jews on a grand scale had always seemed impossible to believe, but once Priska heard about the gas chambers and started breathing in the nauseating stink of roasting human flesh and scorched hair, she was in no doubt that the prisoners spoke the unspeakable truth. The smoke from the dead hung all around them like a shroud. ‘Daily events made it very

clear what would happen to women and to the children of those who were pregnant,’ she said. ‘Logic convinced me that the rate of survival in this hell was very slim.’

In that place of suspended belief, all she knew was that she had to try to save her baby – and that meant not starving to death like the rest of them. Within hours it became apparent that all they would have to live on was liquids, starting with the ‘dishwater’ the Germans called coffee – made from marsh water and burned wheat – which they were given morning and night. At midday, unspeakable soup made from rotten vegetables was slopped out with their only solid food, a small square of black sawdust bread. On such a diet, Priska had too little in her belly to suffer from morning sickness any more.

Following animal instincts to learn the art of survival, she and Edita noticed that the other inmates roused from their stupor in the dark rushed to the fifty-quart kettles of soup the minute they were carried into the block by fellow prisoners. Arguments broke out between cliques and nationalities, while

Kapos

with cudgels or rubber hoses meted out brutal punishments to those who licked at spillages in the dirt or fought like jackals over every revolting morsel. The hungriest endured the blows in order to fish around in the soup with grimy hands for anything substantial. With every scrap they could get vital to their survival, the hand-cleansing rituals of their past were abandoned. Priska saw that it was best to get a ladleful that had been tilted at an angle in the bottom of the kettle, but everyone wanted that and all had to wait their turn.

Once their unwashed bowls had been licked clean and the only light came from the blinding searchlights that swept through the camp at night, she and those she was with attempted to sleep six or more across, lying on their sides on pallet beds in a windowless block that let in rain and wind through every gap in the planking. They had thin mattresses or just dirty straw to lie on, and a thin coverlet between them. They kept their shoes or boots on all night

for fear of theft, and clung to any precious bowls or spoons they might have been given as if they were life rafts.