Belisarius: The Last Roman General (14 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

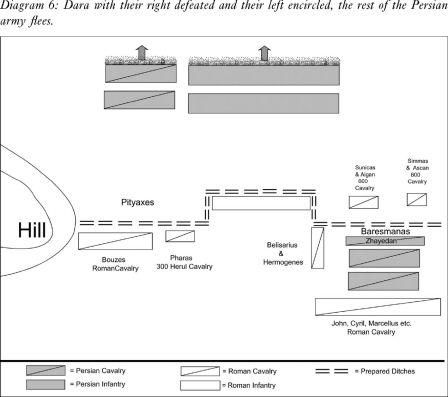

When this second Persian onslaught struck, the Byzantine right wing recoiled. This exposed the flank of the attackers, which the newly-combined troops attacked, driving through the Persians and splitting the Persian army in two. As the Persian wing turned to meet the attack, the recoiling Byzantines rallied and charged. Sunicas killed Baresmanas and the Persian left wing, attacked from two directions, was surrounded, 5,000 men being killed.

At this point, the Persian centre threw down its arms and fled, closely followed by the remnants of the right flank. Many were killed in the ensuing pursuit, but Belisarius and Hermogenes did not allow the chase to continue for long. The Persians were renowned for their ability to recover from a rout and turn upon their pursuers: Belisarius did not want to lose a battle that had already been won.

This was not the end of the fighting. After the battle, the Persians sent an army into Armenia. Surprised by the forces of Dorotheus, the newly-created

magister militum per Armeniam,

and Sittas,

magister utriusque militum praesentalis,

the army was defeated and returned to Persarmenia. Reinforced, the Persians returned and at the Battle of Satala they were again defeated by Dorotheus and Sittas. Finally, Byzantine forces completed the conquest of the Tzani, and the brothers Narses and Aratius, who had earlier defeated Belisarius in battle, deserted to the Byzantines, followed by a third brother, Isaac, who also delivered the fortress of Bolum into Byzantine hands.

At about this time a brief glimpse is given into international politics. The Samaritans, unhappy at Byzantine rule, had previously been defeated in their revolt against the empire. In late 530, five Samaritans were captured in the vicinity of Ammodius, and when questioned under torture they revealed to Belisarius that there had been a plan to betray Palestine to Kavadh. Although unsuccessful, this illustrates the sometimes complex character of politics in the Middle East in the sixth century.

The Battle of Callinicum

In the Spring of 531 the Persians again invaded Byzantine territory. Yet this time there were to be major differences from previous campaigns. Following the advice of the Lakhmid commander Al-Mundhir (Proc,

Wars,

I.xvii.29–40), the Persians under the

spahbad,

Azarethes, invaded Commagene/Euphratensis (see Map 4). Procopius states that this was the first time that there had ever been an attack from this direction by the Persians (Proc,

Wars,

I.xvii.2–3 and I.xviii.3). Furthermore, Al-Mundhir himself accompanied the invasion, along with 5,000 of his troops. When deployed alongside the 10,000 Persian cavalry, the result was that Azarethes fielded an all-mounted army of 15,000 troops.

Caught by surprise, Belisarius at first hesitated in case this was a diversion, and he was unsure what to do about the defence of the traditional line of Persian attack. Eventually, he left garrisons in the cities of Mesopotamia and crossed the Euphrates to challenge the Persians, employing forced marches to catch the enemy. He had also been politically active and had obtained the services of 5,000 Ghassanid troops under Arethas. This gave him a total of 25,000 troops, both infantry and cavalry. Having made contact with the Persians, who had been busy pillaging the countryside, he set up camp at Chalcis, whilst the Persians were in the vicinity of Gabbula.

Faced with a superior force, Azarethes began to retire towards the Persian frontier. Belisarius followed a day’s march behind, often using the deserted Persian camps of the day before to billet his troops. He finally caught up with the Persians in the vicinity of Callinicum on the day before Easter Day, 531.

According to Procopius, there was now a disagreement between Belisarius and his men. Belisarius did not want to give battle as to fight on Easter Day was disrespectful to God. Furthermore, his men would be required by their religion to fast on the day of the battle, leaving them weak and easily exhausted. However, the troops did want to fight and Belisarius eventually yielded to their wishes. The battle would be fought on Easter Day, 19 April 531.

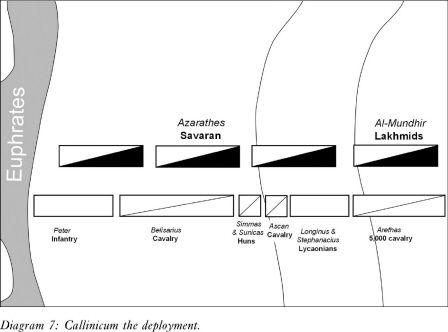

The dispositions of the troops conformed to the terrain. As the Byzantines approached the battlefield, the River Euphrates ran along their left side, protecting that flank from attack. On the right the ground rose sharply. Therefore, Belisarius deployed his infantry, under the command of Peter, a soldier in the bodyguard of Justinian, with their left flank on the river. He personally took command of the centre of the line with the cavalry, whilst to his right were the Huns under Simmas and Sunicas. To their right was a further force of Byzantine cavalry under Ascan, followed by a body of Lycaonian infantry under the command of Longinus and Stephanacius. On the right flank, where the ground rose, he stationed the Ghassanids under Arethas.

On the Persian side, Azarethes stationed his cavalry opposite the Byzantines, with the Lakhmids on his left facing the Ghassanids.

There was now an extensive missile exchange. Although the Persians fired a greater number of arrows, the majority of these were stopped by the Byzantine armour (Procopius,

Wars,

I.xviii.33). In contrast, the smaller number of Byzantine arrows had greater penetrative power, so the outcome was evenly balanced.

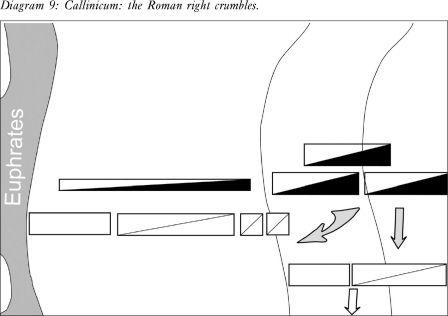

Towards the end of the exchange, Azarethes moved a large number of his cavalry to his left wing, stationing them alongside the Lakhmids. This was to prove critical; a similar move at Dara had been observed by the Byzantines and they had taken measures to counter the attack. This time, the move went unobserved and the attack proved decisive as, not being reinforced, the Byzantine right wing crumbled. The Ghassanids were put to rout, followed by the Lycaonians – Longinus and Stephanacius both being killed. The Byzantine cavalry on the right appear to have resisted, but it was to no avail, with Ascan also being killed in the fighting. Pressure now mounted upon the remainder of the Byzantine line until the rest of the cavalry fled, leaving only the Byzantine infantry to face the Persians. The infantry adopted

the fulcum

formation, the later equivalent of the famous

testudo

(tortoise), used to defend against heavy missile attacks. They formed up in a ‘U’-shape, using the river to close the top of the ‘U’. With foot archers in the centre of the ‘U’ giving overhead supporting fire, the infantry withstood the Persian attack until nightfall, when they escaped over the Euphrates to safety in Callinicum.

It is at the point, where the battle comes to the infantry, that there is confusion in the sources. Procopius has Belisarius retiring to the infantry, giving up his horse and fighting alongside them until nightfall (Proc,

Wars,

I.xviii.43). According to Malalas, Belisarius did not remain, but fled earlier in the battle, escaping by boat across the river. In this version, Sunicas and Simmas were the ones who dismounted with their troops to fight alongside the infantry (Malalas, 464). For reasons that will become clearer shortly, the version given by Malalas is to be preferred.

The Battle of Callinicum had ended in a clear defeat for Rome and Belisarius, wiping out the benefits of the earlier victory at Dara and giving the initiative once again to the Persians. The differences between the two battles now need to be explored.

The circumstances surrounding the two battles were entirely different. At Dara, Belisarius fought a defensive battle within strict geographical limits. Therefore, Belisarius had the opportunity to dig ditches designed for a specific plan, knowing that the enemy would come to fight him at that place as the Persians wanted control of Dara. Furthermore, his position at the centre, possibly on slightly raised ground, gave him a view of the whole battlefield, making it possible for him to see where the enemy were sending their reserves and enabling him to react accordingly. In addition, the Persian reliance on fluid cavalry tactics resulted in a tendency for them to strike at perceived weak points in the enemy line. Belisarius’ use of ditches and his subsequent deployment at Dara allowed him to manufacture apparent weak points, tempting the Persians to attack and enabling him to pre-plan his counterattacks and rout the Persian assault troops.