Belisarius: The Last Roman General (11 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

In 527, the now-ageing Kavadh asked the emperor, by this time Justin, to adopt his son Khusrow in a manner similar to that of Arcadius and Yazdigerd in the previous century. After taking legal advice, Justin offered only a limited form of adoption as befitted a ‘barbarian’; the full form would have entitled Khusrow to inherit the empire. Kavadh understandably interpreted this as an insult, especially since Yazdigerd had proved faithful to the Byzantines in the earlier adoption. Kavadh declared war.

The early war and the appointment of Belisarius

The first Persian attack was upon Iberia, a Christian country allied to Rome, with whom the Persians were at odds over religion. They were promised substantial aid by Rome but received only a few troops to help them. Shortly afterwards the Persians invaded Lazica. The whole country was overrun and the Lazican king, Gurgenes, fled to Constantinople. The initial Persian attacks were a complete success.

The first Byzantine move was an invasion of Persarmenia. Following standard procedures, Sittas and Belisarius led a force into Persarmenia which plundered widely and returned with booty and captives (Procopius,

History of the Wars,

I.xii.20–23). The incident is of note in that it is the first appearance of Belisarius as an individual. Both Sittas and Belisarius are described as bodyguards of the Emperor Justin’s nephew, Justinian (Proc,

Wars,

I.xii.21), although Sittas was soon to be appointed

magister utriusque militum praesentalis

after Justin’s death. It is also clear that Justinian had control of the campaign in the east, although his uncle Justin remained the emperor throughout this period.

Since the expedition had been a success, the invasion was repeated. However, by this time the Persians had been able to make preparations for the defence. In an unnamed battle, Sittas and Belisarius were beaten by the Persians under Narses and Aratius, who we will meet again later. Unfortunately, no details of the encounter survive.

At the same time, a Byzantine force under the command of Libelarius of Thrace, the

magister utriusque militum,

had crossed the border near Nisibis and entered enemy territory. The army, however, retired immediately upon hearing of the defeat in Persarmenia, and Libelarius was reduced in rank for the absolute failure of the attack.

It was around this time that the

dux Mesopotamiae

(commander of the troops in Mesopotamia), Timostratus, died. It is likely that Sittas had been the senior commander during the defeat in Persarmenia, yet, while he retained his post, it is possible that Belisarius’ conduct in the lost battle had been more deserving of note. The lack of a detailed narrative of the battle means we have no way of knowing the truth. Whatever had happened, Belisarius was promoted

dux Mesopotamiae

in place of Timostratus, most likely on the orders of Justinian, consequently assuming command at the headquarters of the

dux

at Dara.

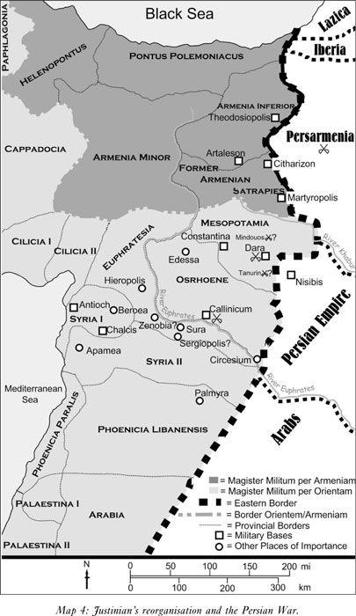

Events were not looking favourable for the Byzantines when Justin died in August and Justinian ascended the throne. Justinian began a major reform of the eastern armies. Apart from revising some of the provincial commands, Justinian also created the post of

magister militum per Armeniam

to help in the war against Persia. As part of the reforms, he brought in a large number of fresh, young officers to command the newly-created positions.

A major part of the strategy against the Persians was the building and maintaining of fortified posts along the frontier, of which the most important was Dara. As a continuation of this policy, an attempt was now made to fortify a site in the desert at Tanurin, south of Nisibis. Realising what was happening, the Persians brought an army to the site and so the work was halted.

To counter this, a Byzantine force was brought together, with a large number of troops under the command of their many individual leaders, including Belisarius; Cutzes, one of two

duces Phoenices Libanensis

(commanders of the troops in Phoenices Libanensis) based at Damascus; and Buzes, the other

dux Phoeni ces Libanensis,

who was based at Palmyra.

Here there is a major fault in our sources. This is the battle described by Procopius as taking place at Mindouos (Proc,

Wars,

I.xiii.2–8). Unfortunately, Procopius appears to have conflated two distinct battles – one at Tanurin and one at Mindouos – into one. Since Tanurin is to the south and Mindouos to the north of Nisibis, it is probably preferable to follow Zacharias Rhetor (Zacharias of Mitylene) and John Malalas and accept that there were two distinct battles. We now, therefore, need to consult Zacharias and Malalas for a clarification of events.

Zacharias

{Historia Ecclesiastica,

ix.2) records the battle as follows:

Accordingly, a Roman army was mustered for the purpose of marching into the desert of Thannuris [Tanurin] against the Persians under the leadership of Belisarius, Cutzes, the brother of Buzes, Basil, Vincent, and other commanders, and Atafar, the chief of the Saracens. And, when the Persians heard of it, they devised a stratagem, and dug several ditches among their trenches, and concealed them all round outside by triangular stakes of wood, and left several openings. And, when the Roman army came up, they did not perceive the Persians’ deceitful stratagem in time, but the generals entered the Persian entrenchment at full speed, and, falling into the pits, were taken prisoners, and Cutzes was killed. And of the Roman army those who were mounted turned back and returned in flight to Dara with Belisarius; but the infantry, who did not escape, were killed and taken captive. And Atafar, the Saracen king, during his flight was struck from a short distance off, and perished; and he was a warlike and an able man, and he had had much experience in the use of Roman arms, and in various places had won distinction and renown in war.

The description shows a common feature of the warfare of this period – the digging and concealment of trenches and pits. On this occasion, the Byzantines failed to detect the pits in time, and so the infantry were defeated, the cavalry escaping to Dara with Belisarius. It is noteworthy that both Buzes and Cutzes are described by Procopius as being ‘inclined to be rash in engaging with the enemy’ (Proc,

Wars,

I.xiii.5). It is possible that they were blamed for the defeat, encouraging their soldiers in a rash attack and so falling into the Persian trap. Despite the loss, Belisarius was yet again not blamed for the defeat.

The same passage in Zacharias

(HE,

ix.2) is also noteworthy in that it gives us our first glimpse of the personality of Belisarius: ‘Belisarius . . . was not greedy after bribes, and was kind to the peasants, and did not allow the army to injure them. For he was accompanied by Solomon, a eunuch from the fortress of Edribath’. This description of Belisarius’ character is informative. His refusal to take bribes, which implies incorruptibility, his willingness to take advice – in this case from Solomon – and his control of the army are all noteworthy. These are attributes that would stand him in great stead later in his career.

After this battle Justinian ordered Belisarius to construct a fort at Mindouos, north of Nisibis. The story is again told by Zacharias

(HE,

ix.5):

The Romans, when Belisarius was duke ... wished to make a city at Melebasa [Mindouos]; wherefore Gadar the Kadisene was sent with an army by Kavadh; and he prevented the Romans from effecting their purpose, and put them to flight in a battle which he fought with them on the hill of Melebasa.

Again Belisarius had been defeated. Yet in 529, possibly as a reward for escaping the defeat at Tanurin and the manner of his conduct at Mindouos, Belisarius was recalled and promoted

magister militum per Orientem

in succession to Hypatius, with instructions to make preparations to invade Persia.

A large army was now assembled and Belisarius advanced towards his former base at Dara. He was joined by the

magister officiorum,

Hermogenes, who was to assist in organising the troops, and Rufinus as an ambassador – for already both sides were contemplating peace (Proc.,

Wars,

1.9–11). There was now a lull in military activities as negotiations began. Although it is not stated specifically in our sources, the time Belisarius now had was probably spent in improving the quality of his army. The army had been dealt a series of defeats at the hands of the Persians. Morale would have been at a very low ebb, and training and discipline in the army appears to have been poor; this is clear from the speech Procopius (

Wars,

I.xiv.14) has Perozes make to his men before the third day of the battle of Dara:

But seeing you considering why in the world it is that, although the Romans have not been accustomed heretofore to go into battle without confusion and disorder, they recently awaited the advancing Persians with a kind of order which is by no means characteristic of them, for this reason I have decided to speak some words of exhortation to you

Although doubtless a literary device to enhance the drama and promote Belisarius’ abilities, there is no doubt a grain of truth in these words. The Persians had won a string of victories over the Byzantines and this would tend to demoralise the Byzantines, making them unwilling to fight and so making their dispositions clumsy and slow.

It is to Belisarius’ credit that he took steps to train the army and improve morale, for the peace negotiations broke down. Before the conclusion of any treaty, the Persians first wanted to take Dara, which had been a source of resentment since its construction by Anastasius. Accordingly, a Persian army of 30,000 men advanced towards Dara led by Perozes, and set up camp near the town of Ammodius.

The Sasanid Persian Army

Although the Sasanid army, like that of the Romans/Byzantines, had also been subject to change over the centuries, this was to a far smaller degree, mainly focusing upon equipment modifications. Following the final overthrow of the Parthians at Firuzabad in 224, many powerful Parthian families had joined the Sasanids. As a consequence, the Sasanid army inherited many of the traditions of the Parthian army, although several details were subject to change.

Sasanid society was divided into four main groupings, namely: priests, warriors, scribes and commoners. The warrior caste, which included royalty, nobles and the aristocracy, was further divided into three classes based upon rank. The first rank was that of the top seven families in the empire. These were the Sasans themselves, the Aspahbad-Pahlov (from Gurgen, north Persia), the Korin-Pahlov (from Shiraz), the Suren-Pahlov (from Seistan/Sakastan), the Spandiyadh-Pahlov (from Nihawand, near modern Teheran), and the Giuw.

The second rank were the

azadan,

or upper nobility. These families could trace their Aryan ancestry back as far as the Achaemenid Empire.

The first and second classes combined to form the

savaran,

the elite armoured cavalry. Included in the

savaran

were some of the elite units of the Sasanid army. For example, there was the Pushtighban (Royal Guards) unit, comprising approximately 1,000 men stationed in Ctesiphon; the Gyan-avspar (Those Who Sacrifice Their Lives), also known as the Peshmerga, formed from men who had distinguished themselves in battle; and the Zhayedan (Immortals) unit, comprising 10,000 men, emulating the Immortals of Darius the Great.

The third rank of the warrior class were the

dekhans,

or lower nobility. Unable to enter the

savaran,

these warriors formed the core of the Sasanids’ light horse archers.

The image of Sasanid infantry is dominated by the

paighan,

or conscript infantry. Equipped with a spear and large shield, their low morale and poor quality is seen to typify the plight of Sasanid foot troops. Their task was to serve as pages to the

savaran,

assault fortifications, excavate siege mines, and look after the baggage train. It is true that they were available in huge numbers; the

Chromnion Anonymum

(66.203.20–205.7) depicts an army led by Khusrow I consisting of 183,000 troops. Of these, 120,000

are paighan.

Yet 40,000 of the total are other Sasanid infantry, with the balance being cavalry.

A major source of foot warriors were the native Medes. Mede infantry could be armed with spear, shield, chain mail and ridge helmets; these were highly regarded and could even be deployed in the centre of the battle line behind the

savaran.

A further source of recruits was the Dailamites. These may have been armed with a mixture of weapons, including battleaxes, bows, slings, and daggers, but Agathias (3.7-9) describes them as carrying ‘both long and short spears [

sarissai

and

xysta

] ... and a sword slung across one shoulder’. Apparently capable of both skirmishing and close combat, they were an infantry force respected even by the Byzantines.