Belisarius: The Last Roman General (9 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

With all of these helmets it must be born in mind that the corroded iron remains that are usually all that is left of the helmet can disguise its form when originally worn. All of the helmets described could be, and possibly were, adorned with gold, silver or other metal sheeting, or might have been tinned to enhance their appearance. Some may also have added paste gems or semi-precious stones to make them even more imposing.

A further option for head protection appears to have been a coif of either chain or scale mail designed to be worn over the head in a similar fashion to a modern balaclava. Unfortunately, although possibly represented in art, no finds of such equipment have been found and the exact design remains in the realm of conjecture.

As a final note, an early seventh-century artefact known as ‘the David and Goliath Plate’ shows infantry wearing highly-decorated cloth covers over the top of their helmets. These would have acted as protection for the helmets themselves in inclement weather, and their decoration could have aided in individual and unit recognition. The date of their introduction is unknown. There is no evidence for their use in the sixth century, due to their inability to survive as archaeological artefacts and the lack of contemporary descriptions and artwork. However their use by the armies of Belisarius remains a possibility.

Armour

For body protection there were, again, a variety of armours that could be purchased. The most familiar of these to modern readers is likely to be chain mail. Small, individual rings of iron are interlinked and riveted together to form a strong and flexible – if very heavy – armour. However, the process of

manufacturing the thousands of iron rings needed, plus the large amount of time necessary to rivet the links together, make this a very expensive piece of kit.

As a second choice there was scale mail. In this, a large number of scales are joined together to form a protective cuirass. The method of joining the scales produced two variations of the armour. In one, the scales are joined with either wire or string to their neighbours to left and right, as well as to a cloth or leather backing material to produce a relatively flexible armour. However, there would be a weakness in the armour between the horizontal rows of scales, which are not joined. In the alternative method, the scales are also joined to the adjacent scales above and below to form a rigid set of armour. The loss of flexibility would be offset against the elimination of the weakness between the rows.

A third form of armour is known as ‘lamellar’ armour. Narrow elongated plates of metal were vertically laced, not wired, to form a very rigid style of armour. Whilst there was little in the way of flexibility, the armour was strong and, due to the method of manufacture, relatively cheap. The form was increasing in popularity at this time under heavy steppe, particularly Avar, influences; this was a fashionable style of armour.

In all of the above examples the armour was designed to cover the torso of the wearer. In addition, fashion now dictated that sleeves were being worn long, usually down to the elbow, and that the skirt of the armour would reach down to the knee. Where necessary, it was designed with a split for ease of wearing by cavalry.

Unless the soldier was prepared to enter battle completely unarmoured, there was one further form of armour he could wear. This was the

thoracomachus

(‘chest/thorax protector’) or

subarmalis

(‘below the armour’), which, as the name suggests, originated as a padded undergarment to be worn below heavy metal armour. There is no archaeological evidence for this armour, yet there are a few pictorial and literary sources available that show it was worn. Similar to the much later medieval akheton, layers of linen or other suitable material were stuffed with a soft filling of some form, for example goats’ wool. This produced a tough, padded armour that could absorb some of a blow’s force, whilst still being very flexible and extremely cheap. Indeed, it is feasible that many of these would have been hand made by the owner to save on armour costs.

To supplement the body armour there was a limited variety of leg, arm and hand armours available.

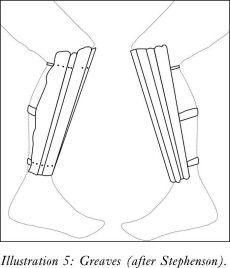

The

ocreae

(greaves) used to protect the lower leg had been in use since before the time of Scipio Africanus in the third century BC. They had evolved from the clip-on version of the early Greek city states into a style that was attached to the leg by leather straps. They were now made from either iron or wood, and were constructed from long pieces which ran vertically up the leg, a form similar to the lamellar armour mentioned above, but in this context known as ‘splint’ armour.

For the arms there were two sorts of defence available.

Manicae

(‘sleeves’) are segmented defences made of iron, copper alloy or leather. They are shown on the Adamklissi monument, where they were probably worn to defend the upper arm against the feared Dacian

falx.

They continued in use until at least the period under discussion, and they are included in the

Notitia Dignitatum

along with the items produced by the state-owned

Illustration

Stephenson).

munitions factories. Although useful in protecting the vulnerable right arm (the left arm being behind a shield), their added expense may have resulted in only a few, if any, being worn by Belisarius’ troops.

The other arm defences available were vambraces. These were made in the same way as the splint greaves mentioned earlier, their difference from

manicae

being that they only protected the lower arm. These may have been in greater demand than

manicae,

since the trend was to wear elbow-length armour and a vambrace would complete the arm protection at relatively little additional cost. However their use by horse archers was probably limited due to their restricting the movement of the right arm, for which flexibility was paramount when drawing and aiming a bow, and the possibility of interfering with a clean release.

Finally, there were gauntlets. These appear to have been made by stitching shaped metal plates onto a leather glove, either worn separately or as an extension of a

manica

or vambrace. Whatever method was used, they would be invaluable in giving the wearer some protection for the otherwise extremely vulnerable right hand. Unfortunately, although we know they were available, there is very little evidence for their manufacture and use. It is possible they they proved restrictive in the use of the bow, and so were deemed unsuitable for use by cavalry units.

Shields

Shields were now made using simple plank construction, with the face at least being covered in leather to help maintain shield integrity. The old plywood shields of the earlier empire were now a thing of the past.

Up until at least the start of this period the use of shields by horsemen had declined but shields began to come back into fashion at roughly the time of Belisarius’ wars. The Byzantine cavalry was now primarily armed with a bow. This necessitated a change in the size and shape of the shields, which now became small and circular, as opposed to the large ovals that had dominated previously. These small cavalry shields were slung from the neck and attached to the upper left arm. This allowed the wearer both to use the bow at distance, and to utilise the limited protection that such a shield offered when in hand-to-hand combat.

Foot archers also appear to have had small shields, which they hung from their belts when not in use. However, these were a last-ditch defence, since the archers were very vulnerable to attack by all opposing troops except for similarly-equipped archers, and would be expected to use evasive tactics if charged.

The spearmen were still expected to use the long oval shield that became common during the preceding centuries, although the size and precise shape of these was likely to be up to the individual purchaser.

All the shields of a given unit would probably have been painted in a ‘regimental’ pattern, or at least the same colour. Yet it should be borne in mind that during the course of a campaign shields were absorbing blows aimed at the bearer, and so could become severely damaged. It is unlikely that field replacements would have been painted with a highly complex pattern; a simple facing colour would have been more likely. It should also be remembered that in a unit with a maximum strength of only 1,200 men, each man would have been known to his comrades, at least by sight.

Weapons

In the employment of weapons, it is likely that the choice would not necessarily have been left to the individual; it is probable that the main offensive/defensive weapon would have been provided by the state – although the cost would then have been deducted from the soldier’s pay. In this way, uniformity of weapons within a unit would help to define the unit’s main function and also eliminate the confusion that could arise from personal choice. Yet it must be remembered that the specific size or weight of, for example, a sword is a personal factor and may have resulted in such weapons continuing to be left up to the choice of the individual.

Spears and javelins

The main weapon for the infantry was the spear or javelin. Although usually seen as being used for different purposes, with the spear being retained in the hand and the javelin used as a missile weapon, there is actually little difference between the two apart from size. It is obvious that the heavier weight of the spear made it harder to throw, whilst the lightness of the javelin makes it less robust as a close combat weapon. Therefore, specialist units who were either designated as shock troops intended only for close combat, or skirmishers intended only for missile action, may have been given weapons of specific size and weight. However, for the majority of troops it is likely that the weapon supplied was of an intermediary size and so could be used for either purpose.

Spicula

and

angones

The classic

pilum

of the earlier empire had now fallen out of use. Its replacements were the

spiculum

(plural:

spicula)

and the

angon

(plural:

angones).

Both of these fulfilled the same function as the

earlier pilum,

but their design omitted the thin metal shaft that extended behind the iron head of the

pilum,

which may have been perceived as a weakness when facing cavalry. They were also easier, faster and cheaper to manufacture than the

pilum.

It is likely that both the

spiculum

and

angon

were still expensive to make when compared to a normal spear, so it is unlikely that they would have been made for universal distribution. Therefore, only the wealthiest of the foot troops may have bought one of these, despite their superiority in most circumstances to other spears and javelins. It is more likely that a minority of specialist units would have been equipped with these weapons by the state.

Plumbatae

Also known as

mattiobarbuli, plumbatae

were a form of dart. In theory there were two types. The

plumbata mamillata

was the standard form, consisting of a shaft, a head and a large lead weight in the centre to aid penetration. The

plumbata et tribulata

had three spikes radiating from the lead weight. This meant that any darts which missed their targets and landed on the ground could instead act as caltrops, with the spikes hindering enemy movement – especially of cavalry. Unfortunately, although there are many examples of the

plumbata mamillata

in the archaeological record, there are as yet no finds of the

plumbata et tnbulata.

Since the weapon is only attested in

De Rebus Bellicis,

written by an anonymous author in the third century, the possibility remains that it did not actually exist except in the imagination of the author.