Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (33 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

For Heudelet, the hero of Davout’s victory over Merveldt at Mariazell in November, things were about to go wrong. Nostitz, detained by Murat during the battle at Schöngrabern, was back with the army. Observing the French struggling to reform, he ordered two squadrons of the 4. Hessen-Homburg-Husaren to attack. Under Oberst Mohr, the hussars charged into the disordered ranks of the left column. Battle-hardened by the constant rearguard actions during the retreat from Braunau, the Austrian hussars slashed their way into the French infantry, causing mayhem. Casualties quickly mounted, and at the same time, the battalion of Brod Grenzer advanced with fixed bayonets towards the right column with Oberstleutnant Desullenovich at their head. The over-extended battalions of 108ème Ligne poured back over the Goldbach, leaving many prisoners behind, while the

voltigeurs

of 15ème Légère covered their retreat. Most veered towards Sokolnitz in an attempt to escape pursuit, but as they did so they unexpectedly ran into a battalion of infantry advancing towards them through the fog. Almost at once the 108ème Ligne were assailed by musketry. All was confusion: the battalion firing on the 108ème was not Russian or Austrian, but the 1/26ème Légère, recently driven from Sokolnitz by Langeron’s II Column. An officer of the 108ème, recognising they were under attack by friendly troops, desperately waved the eagle standard of his battalion until the mistake was recognised and firing ceased. But by now the shaken 108ème were in no condition to take any further part in the battle and retired towards Turas.

20

Telnitz was once again in Allied hands. This time Kienmayer pushed his

grenz

infantry over the stream beyond Telnitz and Stutterheim followed with his cavalry (3. O’Reilly-Chevaulegers and a handful of 1. Merveldt-Uhlanen), as did Generalmajor Moritz Liechtenstein with 11. Szeckel-Husaren, and took up a position west of the Goldbach. Dragging their battalion artillery with them the Russian musketeer regiments of Bryansk, Vyatka and Moscow advanced too, as did 7. Jäger, once they reformed after their earlier scare. However, Buxhöwden still did not intend advancing further until II and III Column were ready to push beyond Sokolnitz, despite the only opposition in

front of him being the recuperating battalions of 3ème Ligne, the 1er Dragons and Bourcier’s dragoon division, all some way off. In the meantime, Buxhöwden contented himself drawing up the Kiev Grenadier Regiment and the musketeers of Yaroslavl, Vladimir and New Ingermanland behind the two artillery batteries overlooking the Goldbach between Telnitz and Sokolnitz.

While the guns at Telnitz fell silent, except for the occasional long-range artillery exchange, matters flared up again at Sokolnitz. Sometime after 9.00am the remaining two infantry brigades of Friant’s division arrived before the village. After their gruelling march from Vienna, only the toughest and most resilient of his men remained. Determined to stifle any major advance westwards by the Russians, Friant ordered GB Lochet to lead his brigade against the village, spearheaded by the 800 men of the 48ème Ligne. With their

voltigeur

company to the fore, led by Lieutenant Pleindoux, the 48ème threw themselves at the south-west corner of Sokolnitz and their impetus carried them right into the village, driving the Russians before them. To their left, the 700 men of 111ème Ligne dashed forward in support and also smashed their way into the village, where they pushed back ‘a huge mass of leaderless men who were advancing in disorder’. Friant’s last brigade, commanded by GB Kister (15ème Légère, reduced to about 300 men by various detachments, and 33ème Ligne with about 500 men), moved to a position on high ground north of Lochet in reserve. Although hopelessly outnumbered by the Russians, the sheer aggression of the attack had their masses milling about in confusion for a moment. However, Langeron reacted quickly and fed the formed battalions of the Permsk Musketeers into the village, as well as one battalion of the Kursk Regiment, retaining the other two battalions as a reserve. This attack drove the 111ème out of the village and cornered the 48ème in the houses and barns at the southern end. Once free from direct attack, the 111ème rallied while the 48ème battled on for all they were worth as the fighting became vicious, desperate and bloody.

To ease the pressure on Lochet’s brigade, Friant ordered Kister’s men into battle. The 15ème Légère charged into the north-west corner of the village as the 33ème Ligne advanced into the space between the village and the castle. Przhebishevsky reacted by throwing two battalions of the Narva Regiment into the mix. Accounts of the fighting tell of individual battle-maddened French soldiers attacking overwhelming numbers of Russians with the bayonet, and of desperate struggles as both sides fought for the possession of treasured eagles and standards. The Russians probably had about 9,000 men bottled up within the confines of Sokolnitz and its immediate area, struggling to get to grips with Friant’s 1,600 to put a stop to his waspish attacks. But no sooner had this new round of fighting got underway than Langeron received some disturbing news. An officer arrived from Podpolkovnik Balk, who commanded two squadrons of the St Petersburg Dragoons and a detachment of the Isayev Cossacks attached to II Column, and informed him that French columns were marching towards

Pratze and the plateau. Langeron listened but could not credit this information. He later wrote:

‘Knowing that the fourth column of Generals Miloradovich and Kolowrat was to be on this side and not receiving any order from Kutuzov, I believed that [Podpolkovnik] Balk had mistaken the Austrians for the enemy, though the direction that he saw them taking appeared extraordinary to me. I ordered him to make a more exact reconnaissance and to advise me of what he could see.’

21

Almost immediately, however, another rider arrived, bearing an urgent message from Count Sergei Kamenski, commander of Langeron’s long overdue brigade. With shocking brevity it confirmed Podpolkovnik Balk’s intelligence and informed the incredulous Langeron that the French were on the plateau; that he had turned his brigade to oppose them; and was facing ‘very strong masses’.

22

While Langeron absorbed this shocking news he must have pondered one crucial question – where was IV Column?

_________

*

Exchange between Grenadiers of 4ème Ligne and Napoleon on the eve of battle,

Mémoires du Général Bigarré

Chapter 14

Storming the Plateau

‘Withdraw us, my General! …

If we take a step back, we are lost.’

*

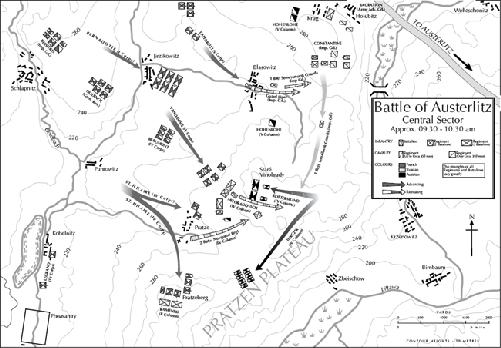

The delays caused by the repositioning of the Russian cavalry did not just affect the advance of the infantry columns on the Pratzen Plateau. Liechtenstein’s V Column of cavalry was required to fill a two-mile gap in the Allied formation, from the northern slopes of the plateau to Prince Bagration’s Army Advance Guard. The Austrian cavalry, commanded by FML Hohenlohe, began to move towards the appointed position between Blasowitz and Krug on time, but with a mere 1,000 men distributed in three regiments, they occupied little ground. Following his orders, Grand Duke Constantine moved the Russian Imperial Guard from its bivouac on high ground north of Krzenowitz and descended into the valley of the Rausnitz stream before taking up a position on high ground east of Blasowitz. Here it was intended to form a reserve for V Column and Bagration’s Army Advance Guard. When Constantine took up his position he observed movement ahead of him near Blasowitz, which he presumed to be Liechtenstein’s men. A discharge of artillery fire in his direction brought him quickly to reality: his Imperial Guard, the only reserve formation of the entire Allied army, was already occupying the front line.

To the right rear of Constantine, Prince Bagration held the main body of his command astride the Brünn–Olmütz road near the Posoritz post house, with outposts ahead of the main force. Bagration’s orders were to hold his position until the left wing of the army gained ground. He expressed unhappiness at his passive role, and having digested Weyrother’s plan in the early hours of the morning, felt sure the army was heading for defeat.

Up on the plateau, following Kutuzov’s meeting with the tsar, General Leitenant Mikhail Miloradovich, the 34-year-old joint commander of IV Column, issued the orders for the leading Russian elements of the column to move off.

Miloradovich was the grandson of a Serbian asylum seeker who came to Russia to escape Turkish oppression. His father amassed a fortune while rising through the Russian civil ranks and became very powerful in the process. As an officer in the Izmailovsk Guards, Miloradovich came to the attention of Grand Duke Constantine, the two becoming friends, and by the age of twenty-seven he had risen to the rank of major general. However, he squandered his father’s fortune, and according to Langeron, was conceited, thoughtless, insolent, and knew little of military matters beyond the parade ground. Langeron also considered that Miloradovich felt a strong desire to be the first in everything, whether ‘in battle, a ball or an orgy’.

1

As the leading battalions marched off, Miloradovich took few precautions for the security of his column. Marching so close behind Przhebishevsky it was logical that the route ahead must be clear of the enemy. Maior Karl Toll, who had spent a sleepless night ensuring Weyrother’s plan was translated and despatched to the column commanders, now rode ahead of IV Column towards Kobelnitz, accompanied by a single Cossack rider. Some distance behind Toll marched two battalions of the Novgorod Musketeer Regiment and the grenadier battalion of the Apsheron. Two artillery pieces and two squadrons of the Austrian 1. Erzherzog Johann-Dragoner accompanied them, all under the command of Podpolkovnik Monakhtin. These leading units were earmarked to occupy Schlapanitz, on which the rest of the Allied army was to pivot.

2

Behind this advance guard, Miloradovich followed with the rest of the Russian troops of IV Column: nine battalions formed in two brigades commanded by General Maior Grigory Berg and Sergei Repninsky. Then, behind the Russians, FZM Johann Karl, Graf Kolowrat-Krakowsky, a 57-year-old Bohemian nobleman with forty years’ military experience, led forward the Austrian contingent: the brigades of Generalmajor Rottermund and GM Jurczik. In this relaxed manner these final formations prepared to abandon the Pratzen Plateau.

Back at Napoleon’s headquarters on Zuran Hill, the emperor waited for the news that the Allies had abandoned the plateau. Then, after his discussion with Maréchal Soult, he released the commander of IV Corps to lead the divisions of Saint-Hilaire and Vandamme against the vacant heights.

Soult galloped off to Puntowitz, where Saint-Hilaire’s division stood, having already passed through the village. Although only just over a mile from Pratze, it had remained invisible to Przhebishevsky’s III Column as it marched through the village en route for Sokolnitz, hidden in the fog and smoke, which hung heavily in this section of the valley floor. Soult well understood the importance of his orders and rode up and down the division calling on individual regiments

to echo former glories. A triple issue of army brandy further enhanced their enthusiasm for the fight. With his men now fortified in mind and body, Louis Saint-Hilaire, the brave and talented 39-year-old divisional commander, ordered his men forward, leading with the two battalions of 10ème Légère, the single unit forming GB Morand’s brigade. Morand’s orders were to move onto the high ground to the right, or south side of Pratze village. The brigade of GB Thiébault followed Morand with two battalions each from 14ème and 36ème Ligne. Varé’s brigade (two battalions each of 43ème and 55ème Ligne) marched in reserve, but once on the plateau, they were to form a link with Vandamme’s division. As the division emerged from the gloom of the valley into the sunlight, the leading men saw the tail of Przhebishevsky’s III Column disappearing towards Sokolnitz, completely unaware of the presence of this French force behind them. However, tempting though this target was, Saint-Hilaire continued towards Pratze, leaving the task of facing III Column to Legrand’s division, which was defending the line of the Goldbach. Ahead of him all that now appeared to stand between his division and their goal were two riders emerging alone from Pratze: Maior Toll and his Cossack companion.

Toll presumed that these shadowy men in the distance must be a part of III Column that had lost its way. Then the crack of a musket and a puff of smoke focused his attention and he realised with horror that this was no wayward Russian column, it was a major French attack and he was directly in its path. Toll and his comrade turned quickly and galloped back to the plateau. Warned by the breathless major, Monakhtin hurriedly led the two battalions of the Novgorod Musketeers forward. He placed one on the high ground on the south side of Pratze and moved the other through the village and turned southwards over a bridge that crossed a wide, steep-sided stream running down to the Goldbach. Taking advantage of the ground, he concealed this battalion from the French. The Apsheron grenadier battalion acted as a reserve in the village with the 1. Erzherzog Johann-Dragoner further back supporting the left.