Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (30 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

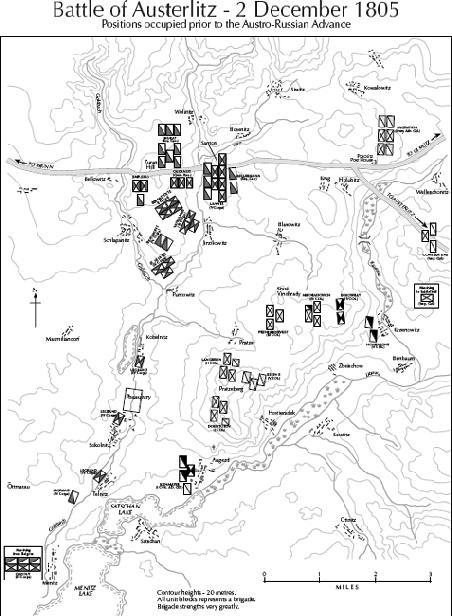

Once back at headquarters, Napoleon prepared his plan of battle based on the latest movements of the Allies, and at about 8.00pm he assembled his senior commanders to issue them with their orders and divulge his plans in detail. As he did so, the concentration of the French army on the left was complete. Suchet’s division of V Corps stood across the Brünn–Olmütz road close to the Santon, extending towards the village of Jirzikowitz, with a detachment manning the Santon. Caffarelli’s division, now attached to V Corps, drew up behind them. Bernadotte arrived with his corps during the day and fell in to the rear of Caffarelli. Murat, with the Cavalry Reserve, occupied a position behind this left wing of the army. Oudinot’s grenadier division formed to the east of Zuran Hill, while the Garde Impériale occupied a position on the west side, between the hill and the village of Bellowitz. Two of Soult’s divisions – Vandamme and Saint-Hilaire – formed on the hills behind Jirzikowitz and Puntowitz, with Vandamme to the fore. To cover all the ground south of Puntowitz, Soult’s final infantry division – Legrand’s – concentrated behind Kobelnitz with detachments extended in a thin string along the Goldbach stream to Telnitz, where the small battalion of Tirailleurs du Pô occupied the village.

The orders required Vandamme and Saint-Hilaire to have crossed the stream to their front by 7.00am and Legrand to occupy Kobelnitz. While Soult’s corps took up these new positions, Suchet was to narrow his frontage by reforming his division, moving his right hand brigade behind his left brigade. Caffarelli would occupy the space freed up on Suchet’s right. As Caffarelli moved forward, Bernadotte’s men moved to occupy the ground he vacated, taking up a position with his left to the rear of the Santon. Oudinot’s grenadiers were to move forward, placing their left behind Caffarelli’s right. During the day, Davout rode back to rejoin his fatigued men, who continued on their extraordinary march, his new orders reaching him on the road. By the evening Friant and Bourcier made camp near the monastery at Gross Raigern. In forty-eight hours these men had marched a phenomenal 65 miles and, although almost half of the men dropped by the wayside unable to keep up the pace, the

4,000 men that remained were now only a little over 5 miles west of Telnitz, within touching distance of the battlefield.

Davout’s orders required his men to be on the road again at 5.00am, marching to a position near the wood at Turas, some 31/2 miles west of Kobelnitz, from where they could support Soult’s weakly held right flank. At the conclusion of the meeting, all the marshals were instructed to return to headquarters at 7.30am in case enemy movements during the night necessitated significant changes. The result of these careful dispositions meant that much of the great concentration of the army took place hidden from prying eyes. While the left manoeuvred into position, strongly anchored on the fortified Santon, the far right, south of Kobelnitz, remained extended and weak, but it could expect to draw support in the morning from Davout.

Napoleon then explained his plan. He hoped to draw the Allies from the plateau, encouraging them to attack him along the line of the Goldbach, where he would attempt to delay them for as long as possible. Then, when the Allies had weakened their concentration on the plateau, he planned to launch his centre on a rapid advance against this high ground from where, once established, he could operate in strength against the rear and flanks of the Allies. Meanwhile, the left would advance and brush aside any opposition before wheeling to the right and completing the encirclement of the Austro-Russian army.

Even as Napoleon explained his intentions, riders passed amongst the army distributing a proclamation, announcing his basic plan to even the most lowly novice soldier. Reproduced on the emperor’s mobile printing press, it informed his soldiers that they faced a Russian army determined to avenge the Austrian army of Ulm. But he assured them of the strength of their positions and added that ‘while the enemy march upon my batteries, they will open their flanks to my attack’.

3

He urged them to ‘carry disorder and confusion amongst the enemy’, but asserted that should victory appear uncertain for a moment then he would join them in the front rank. But most importantly of all, he promised that victory would bring an end to the campaign and with it the reward of rest and peace. The proclamation did not reach Lieutenant Sibelet and the 11ème Chasseurs à cheval in their exposed bivouac behind Menitz until 1.00am. Unwilling to attract enemy attention to their position, an officer read it to the men by the light of a candle shrouded under a coat. Sibelet recorded that his men, inspired by the emperor’s words, vowed to ‘overcome or die’.

With the French army in position, seeking warmth, food and rest on another freezing night, the Allies were still stumbling up the steep eastern slopes of the Pratzen Plateau, searching for their appointed camping grounds in the dark. General Leitenant Dokhturov led his I Column – about 9,500 men – to encamp at the southern end of the heights, above the village of Augezd, detaching a battalion of

jäger

to occupy the village. General Leitenant Langeron took up a position between Dokhturov and the village of Pratze with II Column (some

11,500 men). General Leitenant Przhebishevsky brought III Column – approximately 8,400 men – onto the heights to the right of Pratze. All three of these columns, forming the left wing of the army, came under the overall command of General Leitenant Buxhöwden and were composed of Russian troops.

FML Kienmayer’s command, a mixed Austro-Russian formation about 5,500-strong, operated as an advance guard for I Column. As soon as the columns began to arrive in strength and occupy the plateau, Kienmayer headed south to post his men below the heights in front of Augezd, having been reinforced by five battalions of Austrian

grenz

infantry, transferred to his command during the day.

The IV Column, another mixed formation, under the joint command of the Russian General Leitenant Miloradovich and the Austrian Feldzeugmeister Kolowrat, advanced with about 14,500 men to camp on the plateau in the rear of III Column.

FML Prince Liechtenstein now commanded the main cavalry force, a mixture of Austrian and Russian regiments, some 5,300-strong. Although detailed to camp below the plateau in the rear of III and IV Column, in the confusion, part of the column spent the night on the plateau close to Langeron’s II Column.

On the far right, Prince Bagration, commanding the Army Advance Guard – about 12,700 men – maintained his position across the Brünn–Olmütz road, but pushed his left beyond Holubitz towards Blasowitz, to offer flank protection to the march of the army.

The Imperial Guard, with 9,000 men, provided the army’s only reserve and took up a position on hills to the north of Krzenowitz, in which village the Allied command set up its headquarters.

4

From his position on the Zuran Hill, Napoleon’s gaze followed the crest of the Pratzen from north to south. Now, all along the summit, the glow of camp fires revealed the position of the Allied army as it prepared for battle. Then, some distance away to the south, the sound of firing caused concern and he despatched a number of staff officers to investigate.

The firing came from Telnitz, some 6 miles away. After Kienmayer moved off the plateau to the position in front of Augezd he pushed the 3. O’Reilly Chevaulegers towards Telnitz to feel for any opposition. At the village they encountered the Tirailleurs de Pô. Taken by surprise the Italians offered a brief firefight in the dark before abandoning the village to the Austrian cavalrymen, who left a half-squadron garrison and returned to Augezd. Alerted now to what had taken place, Napoleon rode south with Soult and a small suite of officers and attendants to investigate for himself. This move against Telnitz had surprised Napoleon and he recognised a need to strengthen this southern end of the line. But before the party could return, they ran into one of Kienmayer’s probing Cossack patrols. In that brief moment the life of

Napoleon hung in the balance and with it the outcome of the campaign. However, the small group evaded capture, although the horse of Napoleon’s surgeon, A.U. Yvan, became stuck in the mud by the Goldbach and had to be pulled free before the whole group dashed back to the French lines: the coming battle alone would decide the destiny of Europe.

As he returned to his headquarters, Napoleon passed through the bivouacs of the army. Discovering the emperor in their midst, soldiers grabbed handfuls of straw from their rough shelters, and setting fire to them, attached them to poles culled from the surrounding vineyards. Holding them aloft to light his way they cheered his progress with cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ Others took up the cry, adding to the fiery river of light that extended through the camps. This impromptu display of devotion by the army greatly moved Napoleon, coming as it did on the eve of battle and the eve of the first anniversary of his coronation as emperor.

5

This sudden eruption of light and commotion in the French lines startled the Allied outposts too. Yet far from being taken as an indication of the extent and concentration of the French army, many in the Allied camp saw it as confirmation of the rumours that were rife: that La Grande Armée was about to retreat.

6

As the French army settled down again, Napoleon began to revise his orders in respect of what he had seen at Telnitz. The campfires he observed in front of Augezd and the attack on Telnitz suggested an Allied attack directed further to the south than originally anticipated. It would be necessary for Legrand to extend his division southwards to increase the security of the villages of Telnitz and Sokolnitz. Accordingly, in the early hours of the morning the 3ème Ligne attacked Telnitz, drove out the Austrian cavalry and recaptured the village. GB Merle’s brigade formed to the north of Telnitz; the two single battalions of the Tirailleurs du Pô and Tirailleurs Corses covering Telnitz and the riverbank between Telnitz and Sokolnitz, with the two battalions of 26ème Légère ordered to march for the village of Sokolnitz. GB Lavasseur, with the final brigade of Legrand’s division, occupied Kobelnitz and extended towards a large walled park north of Sokolnitz, known as the Pheasantry. This repositioning affected other formations too. Saint-Hilaire received orders to move his division from the second line and advance to a position on the right of Vandamme from where he was to prepare to cross the stream at Puntowitz. However, by the time he received the order at about 3.00am, a thick fog had descended on the valley and the division, unable to move, remained in position until morning.

7

Bernadotte, assigned to support Lannes, received orders to realign to the south, behind Vandamme’s left.

The Allies, too, were busy finalising their plans. At 11.00pm, with the Allied army now established on the plateau, orders arrived directing the column commanders to assemble at Krzenowitz to receive orders for the following day. All except Bagration attended. At about 1.00am, when all were assembled, Weyrother arrived after an exhausting day in the saddle and spread a large and

detailed map of the area between Brünn and Austerlitz on a table. According to Langeron he then:

‘read us the arrangements in a raised voice and with a conceited air which was designed to show us his deep-seated belief in his own merit and in our inability. He resembled a high school master reading a lesson to some young school children: we were perhaps likely schoolboys but he was far from being a good teacher. Kutuzov, seated and half asleep since we arrived at his place, eventually did fall asleep completely before we left. Buxhöwden, standing, was listening and certainly understood nothing. Miloradovich kept quiet, Przhebishevsky stood at the back and Dokhturov was the only one who examined the map with any attention.’

8

Weyrother described his plan in painstaking detail – in German – and waited patiently while a staff officer, Maior Toll, translated each section into Russian. In essence, he explained that the Allied army extended beyond the French right, so in by-passing it and occupying the villages of Telnitz, Sokolnitz and Kobelnitz, they could push onto the plain beyond. Then, advancing between Turas and Schlapanitz, they would throw the French back to the difficult hilly ground to the north. I Column was to attack Telnitz, II Column targeted the valley between Telnitz and Sokolnitz, and III Column Sokolnitz Castle. Once past the Goldbach, the columns were to wheel northwards with the head of each column in alignment. Moving last, IV Column was to pass to the right of Kobelnitz, align itself with the first three columns, and swing north towards Schlapanitz. Bagration was to hold his ground until he saw IV Column turn north, then he was to march straight ahead and engage the French left. However, Weyrother’s plan presumed the main French strength to be occupying a position further back than it was, between Schlapanitz and Bellowitz. This lack of understanding of the French position is epitomised by the fact that Liechtenstein’s cavalry column was instructed to push onto the heights ‘between Schlapanitz and the Inn of Leschern’. This position lay close to the Santon and would place it but a mile from Napoleon’s headquarters and within touching distance of Vandamme’s division. The final component, the reserve formed by the Imperial Guard, was to advance to a position behind Blasowitz and Krug, to support Liechtenstein and Bagration.