America's Prophet (19 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

Orators saw parallels in the rebellions both leaders faced. “When his own people lost heart and confidence, and found fault with him,” one preacher said, Moses “never once thought of giving up…. How like Moses, in these respects, was our late President?” Unlike Washington, Lincoln was not a universally beloved figure at the time of his death, and a number of speeches tweaked the late president by pointing out that, like the Israelites, Americans might have a better chance of reaching the Promised Land with a new leader. Moses was fine for the wilderness, but Israel needed a Joshua to finish the job. “In Abraham Lincoln God gave us just the man to take us safely through the last stages of the rebellion,” said a reverend in Boston. “But the nation had now reached the Jordan, beyond which were sterner duties.” He concluded: “We have passed the Red Sea and the wilderness, and have had unmistakable pledges that we shall occupy that land of Union, Liberty, and Peace which flows with milk and honey.”

While these speeches were being delivered, Henry Ward Beecher was sailing back to New York. He finally delivered his highly anticipated eulogy in an overflowing Plymouth Church on Sunday, April 23. He began with a long recitation of the final chapter in the

Five Books of Moses, Deuteronomy 34:1–5: “So Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho.” God then gives Moses a face-to-face tour of the full dimensions of the Promised Land—from the fields of Galilee in the north, to the Negev desert in the south, to the Mediterranean in the west. “This is the land of which I swore to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,” God says. “I have let you see it with your own eyes, but you shall not cross there.” Moses sees the land. He is close enough to see that God has fulfilled his promise. But he will not enter. The parallels with Lincoln were rich.

“There is no historic figure more noble than that of the Jewish lawgiver,” Beecher continued. “After so many thousand years, the figure of Moses is not diminished, but stands up against the background of early days distinct and individual as if he had lived but yesterday. There is scarcely another event in history more touching than his death.” Until now, Beecher suggested. “Again a great leader of the people has passed through toil, sorrow, battle, and war, and come near to the promised land of peace, into which he might not pass over. Who shall recount our martyr’s suffering for this people!”

Four score and nine years after Thomas Paine likened America’s independence to the Israelites’ flight from Egypt, and two-thirds of a century after George Washington was eulogized as America’s Great Liberator, Americans once more turned a national tragedy into an opportunity to bind their story to the three-thousand-year-old narrative of nation building forged in the wilderness of Sinai. And once more Americans likened their leader to Moses. The persistence of Mosaic imagery at nearly every major turning point in the country’s formative century shows how clearly the themes of chosenness, liberation from slavery, freedom from authority, and collective moral responsibility had become the tent poles of American public life.

But in the case of Lincoln, was the analogy apt?

Before leaving Allen Guelzo’s office, I asked him which comparison he would have chosen—Jesus or Moses—if he had been invited to give a eulogy for Lincoln. He clapped his hands together delightedly and rocked back in his chair. “Hmmm,” he said. Then he thought for a full minute.

“I think it goes back to what we think Lincoln’s greatest achievement was,” he finally said in a whisper. “If Lincoln’s greatest achievement was emancipation, then we’re going to talk about him as Moses. If we think Lincoln’s greatest achievement was redeeming the country from the onus of slavery, then we’re going to talk about him as Christ.”

“I would have thought Jesus was a much more influential figure in America,” I said. “But I’m starting to believe the themes of Moses may echo more.”

“Put it this way,” Professor Guelzo said, “the story of Jesus is extremely important. What is surprising is how persistently important the story of Moses remains. After all, if you take this from the point of Protestant theology, Moses is great but Moses is the old covenant. But that’s not how it plays out. The real story is not why Christ is so attractive, but how did Moses get on the stage. And why is he still here?”

“So what’s your answer?”

“I think it’s a message about American identity. It’s like kids identifying themselves with baseball players. Cultures do the same. Our icons tell us who we are. In this case, the Moses-Jesus track comes down to which is more important: deliverance or redemption?”

“That brings us back to the question,” I said. “If you had to compare Lincoln with Moses or Jesus, which would you choose?”

“It depends on how much I knew about Lincoln,” he said. “If I

knew a lot about Lincoln personally, I’d probably say he was more interested in redemption. But if I only knew him as the president, the guy in Washington, the man of emancipation, I’d say he was more focused on deliverance. The private Lincoln is more like Jesus, but the public Lincoln is more like Moses.”

MOTHER OF EXILES

I

STEP OUT

of the Bowling Green subway station in lower Manhattan, stride past the battered sphere sculpture salvaged from the World Trade Center, and pass through security at Coast Guard Headquarters. The guard directs me to a pylon at river’s edge, and suddenly I’m in a different world. The dock is a tangle of buckets, ropes, barnacle-crusted buoys. A seagull flutters in the briny air. To my left is a four-story orange ferryboat,

Miss Liberty.

Across the inland chop is a giant air vent for the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, and between us is a never-ending crisscross of water taxis, tugboats, and garbage barges. Far from the glittering lights of Fifth Avenue, this is industrial New York. The harbor as infrastructure. The city as work.

To my right, framed by the slate sky and a tangle of steel cranes, is the ultimate icon of industrial age America. The towering giant of copper and steel was conceived as a pagan symbol, meant to exude

Old World muscle. But by the time the New World got through reinterpreting it, the 305-foot colossus had become the standard-bearer of America’s escape from tyranny, its commitment to freedom and law, and its role as the new Promised Land. Just when America’s connection to Moses was tarnished by its association with the losing side of the Civil War, along came the country’s most captivating symbol yet and a renewed link to its Mosaic past.

Along came the Statue of Liberty.

THE

ROSEMARY MILLER

,

a small coast guard vessel, docks at the pier, and a half-dozen commuters walk up the short plank and gather in the open air at the stern. Many carry brown-bag lunches or crumpled plastic sacks. One wears a hard hat. Ignoring the wind, a few are trying to talk on cell phones or listen to iPods. These workers are taking the morning commute to Liberty Island, and as the boat pushes off from the shore, all of them are leaning against the rail or huddled in small groups, looking north. The statue is south. I had been invited by the monument’s chief historian to take the staff boat to the island, and my first impression is that if you are exposed to the statue often enough, even the country’s beacon of hope can become a mere backdrop. As the boat splashes into the harbor I risk exposing myself as a newbie when I defiantly look south.

At the close of the Civil War, the country’s most profound shock may have been the damage to its self-image as a chosen people, selected by God to create a biblical kingdom on earth. Even more destabilizing, the closing decades of the nineteenth century brought a dizzying barrage of intellectual movements, economic transformation, and scholarly invention that collectively constituted the biggest threat to the Bible’s authority in its nearly two millennia of influence. Charles Darwin published

The Origin of Species

in 1859, initiating

a direct assault on the biblical idea that God created the world in six days. Also, literary critics exploded the traditional view of who wrote the Bible. Custom held that Moses wrote the books that bore his name; David wrote the psalms; and the prophets wrote their books. Scholars now argued that different authors composed the stories, often long after the events described. Educated people were forced to accept that the Bible may contain the word of God but also contains the work of scribes. Overnight, everything known about the Israelites was open to question. Did Moses really turn the Nile into blood? Did he really part the Red Sea? Did he even exist? And what about God?

God’s New Israel particularly felt the impact of these changes. In less time than the Israelites are said to have spent in the desert, the United States went from a predominantly rural nation to a highly urban one, from a mostly agricultural economy to a heavily industrialized one, from a deeply religious society to a more secular one. The “age of belief” gave way to a “scientific revolution.” The grip of evangelicals gave way to wave after wave of Catholic and Jewish immigrants. By 1900 it became clear that if the nineteenth century had been America’s Protestant century, the twentieth century would be something else entirely. And that raised a question: If America’s focus on the Bible was diminishing, would its attachment to Moses lessen as well?

ON A GRAY

approach from Manhattan, the Statue of Liberty doesn’t quite stir the soul as the postcard images would suggest. Her mint color seems more chilly than star-spangled. She faces south, meaning that for much of the ride you’re viewing her from behind. The shadows in her folds look streaked in soot. From the rear, she appears to be sagging under the weight of her gown. Not until the

boat passes under her feet does my heart skip a beat at her Olympian splendor: her firm grip on the tablet in her left arm, the seven bolts of light from her crown, and the erect majesty of her right arm, with the twenty-karat flame managing to brighten the gloom. The shock of gold in the otherwise dreary environs reminds me of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

Barry Moreno was not what I had expected. On the phone, the chief historian of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island sounded like a pencil pusher who wore a green visor and toted a tuna fish sandwich to the island every day. I would have pegged him for balding and fifty. In person he looked like a backup singer for Madonna. He wore fashionably flared jeans, trendy shoes, and a yellow, polka-dotted dress shirt with unbuttoned French cuffs. The son of an Egyptian mother and a Cuban-Italian father, he also has long, lithe fingers that he bends back in the manner of a yoga instructor.

“I first visited the statue in 1988 when I was hired as a temporary ranger after college,” Moreno explained. “I took a train from California. I had never been to New York, and I was stunned by the statue. She was so historic. Not quite as great as a monarch, but something close to the glory of a king.”

He never left. A first-generation polyglot American and a sponge for languages, Moreno was a perfect Boswell for

Liberty.

He has since written one book and one encyclopedia on the subject in English and was cowriting another in German, and in order to examine all the immigrant documents that came into the library, he had managed to learn French, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, Afrikaans, Romanian, Portuguese, and Catalan. “They’re all related,” he said nonchalantly, as if the task was as simple as collecting his mail.

Moreno led me up the broad sidewalk, through the tightest security I’d ever seen, and into a small museum at the base of the statue.

A giant, life-sized mask of

Liberty

’s face peers out from the entrance, not as serene as the

Mona Lisa,

more sternly serious. Alongside it are some of the wooden molds used to hold the 200,000 pounds of molten copper, which were pounded into 310 sheets, each two pennies thick. Nearby is a model of the steel interior designed by Gustave Eiffel, which anticipated the Eiffel Tower that was built the following year.

Liberty

’s pageantry may be American, but her infrastructure is pure French.

“When I was growing up, I knew the statue as a great symbol of the United States,” Moreno said. “But when I first came here, many aspects of her origin were simply fuzzed over. The Park Service didn’t want us to do our own research. It was not until I started doing my own digging that I really understood the story.”

The birth of the Statue of Liberty grew out of the death of Abraham Lincoln. The news of Lincoln’s assassination arrived in France at a time when the country was rent by a generation-long struggle between republicanism and monarchism. In the spring of 1865, under the regressive regime of Emperor Napoléon III, French liberals were struggling to articulate a viable model for representative democracy, and they turned to the United States. The approaching centennial of the Declaration of Independence offered the ideal time to hail American liberty, remind the world of France’s role in bankrolling that freedom, and forever align the two countries. At a meeting outside of Versailles, Americaphile Édouard de Laboulaye, the author of a history of the United States and an avid abolitionist, conceived the idea of presenting a monument to the United States as a gift. At least one man in the group thought it was a good idea.

Frédéric Bartholdi was not exactly an Americaphile. But the thirty-three-year-old sculptor was a classicist, a lover of Egypt, and likely a Mason, since he had put his face on a Masonic sculpture in Paris and sculpted Washington and Lafayette in a supposed Masonic

handshake. He also loved grand gestures, all of which made him uniquely suited to tackle the complexities of raising money for a work modeled partly on the Colossus of Rhodes, one of the original Seven Wonders of the World. In back-to-back trips to Egypt and the United States, Bartholdi honed the idea of a tribute to liberty that would draw its size from pharaonic monuments of Rameses II and be placed in New York Harbor. It should be seen “from the shores of America to the coast of France,” Bartholdi said. To boost sagging fund-raising, Bartholdi sent a model of the torch to Philadelphia in 1876, then to New York. Joseph Pulitzer helped with the final push by appealing to readers of the

World

. On August 11, 1885, the

World

showed Uncle Sam bowing down to Lady Liberty on the occasion of topping one hundred thousand dollars in donations. The torch was being passed to a new American symbol.

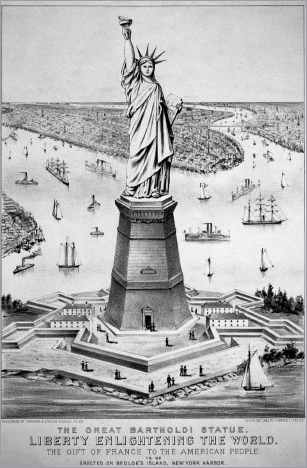

But what did the statue, officially called

Liberty Enlightening the World,

represent?

“To me, she’s a Roman, pagan goddess,” Moreno said. He had brought me to a spot deep in the pedestal where the original torch is displayed. “Nearly everything about the statue is Greek or Roman. She’s dressed in totally Roman garb. Her hairstyle is from that time. She strides forward in a neoclassical way.”

“But France and America were largely Christian,” I said. “Were people offended?”

“Bartholdi knew that no figure customarily represented the American people. On maps, female Indians had been used to symbolize the United States. But classical imagery had been popular in Europe for centuries, and even in America, our courthouses and post offices were built as Greek and Roman temples. Plus, she does have a lot of non-pagan influences.”

“So let me ask you about a few of those,” I said. “Is it significant that Bartholdi was a Mason? He met with Masons when he came to

New York. Masons raised a lot of the money, and Masons actually constructed the pedestal.”

Liberty Enlightening the World,

with ships and New York Harbor in the background. Lithograph published by Currier & Ives, c. 1886.

(Courtesy of The Library of Congress)

“Bartholdi believed that Masons had some secret to democracy,” Moreno said. “They were connected to the breakdown of the authoritarian models of government and hierarchical, ritualistic religions. Plus they supported new interpretations of the Bible and the idea that certain elite people share a secret message of freedom.”

I ticked off a series of the statue’s prominent symbols and asked Moreno what they represented. A number seemed as if they were taken directly from the Bible. I started with the chains and shackle at Liberty’s feet.

“Ostensibly they symbolize independence from England, but secretly they mean other kinds of servitude—slavery, tyranny, any kind of oppression in the world. That’s why immigrants and refugees legitimately saw the statue as a symbol of their freedom.”

The crown. Roman depictions of Liberty often showed her with a soft red bonnet, called a Phrygian cap, given to Roman slaves when they were freed. The U.S. Capitol was designed with a Liberty on top wearing one of those bonnets, though the statue was renamed

Freedom

and the cap replaced with a helmet of an eagle’s head. Bartholdi scuttled the cap in favor of a nimbus, a gold circle of light in the shape of a crown with seven pointed sun rays, one for each continent, or ocean, or day of God’s creation. As Moreno noted, the Roman sun god Helios was also shown wearing a spiked crown, as were Roman emperors, even Constantine. The motif of a halo around the head of a significant person was commonly used in medieval and Renaissance art, especially for Jesus.

But the notion that light should envelop the head of an exalted figure is introduced in the Hebrew Bible, predating all of these uses. In the first sentence of Genesis, God is associated with light as he

utters the earliest words ever spoken: “Let there be light.” God later appears to Moses in an illuminated burning bush, and he appears to the Israelites encamped at Mount Sinai as “a consuming fire on the top of the mountain.” The first human to have his presence infused with God’s light is Moses. In Exodus 34, when Moses descends from forty days on Sinai carrying the “two tablets” of the covenant, he “was not aware that the skin of his face was radiant, since he had spoken with the Lord.” The Israelites shrink from Moses because his face is luminous and he veils himself to protect them. The story of the Exodus predates the Byzantine, Christian, and classical Greek and Roman eras, so Moses—not Helios, Nero, Jesus, or Constantine—introduces the nimbus into Western imagery. A misinterpretation of a Hebrew expression in this scene,

karan orh pahnav,

which can be read “ray of light” or “horn,” produced the idea that Moses had horns. Michelangelo memorialized the horns in his statue of Moses, and they are echoed in the spikes around the forehead of Bartholdi’s

Liberty Enlightening the World

.