America's Prophet (32 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

“How much of Moses’ message on Mount Nebo is ‘Take care of your own house?’” I asked, “and how much is ‘Take care of your neighbor’s house, too?’”

“Ninety percent is take care of the house of your neighbor—maybe even more than ninety. The whole idea is that this is a communal enterprise. It is the biblical ethos that says, ‘You can’t make it through this world alone. You can only make it in community.’”

“So when I sit down with my daughters at future seders, what should I tell them is the story’s central lesson?”

“That in every generation, there are forces, individual and collective, that try to inhibit our human fulfillment. And in every generation, God acts as the impulse to strike out for freedom, even though the path to freedom is not always easy. But in the end, the burden is on each of us to finish the journey. When we were slaves, God had to break our chains. We couldn’t do it for ourselves. In fact it took an outsider like Moses to be a catalyst, as it took an outsider like Martin Luther King, Jr., to lead the civil rights movement. But once we’re no longer slaves, we can’t say to God, ‘Fix this for us.’ Now we have the opportunity and obligation to fix it for ourselves.”

I’VE BEEN TO

a lot of seders in my life. When I was growing up, my parents used a popular

hagadah

with contemporary watercolors, abundant songs, and readings from Anne Frank, Abraham Joshua Heschel, and others. Published in 1974, the book was unabashedly

liberal; it says of the plagues, “Our triumph is diminished by the slaughter of the foe.” In Jerusalem one year, I attended a more traditional seder where they read every prayer and followed every dictate and the evening didn’t end until 2

A.M

. That night answered a question I’d had since childhood: In Jerusalem they also end the service by saying, “Next year in Jerusalem.”

The start of Passover brings the two nights a year when my father-in-law, Alan, an attorney and elder sage around Boston, is in charge of a portion of his home, which is otherwise dominated by women. In keeping with contemporary Jewish custom (and in violation of international copyright laws) he has gone through numerous

hagadah

s and pieced together his own service. The word

seder

means “order,” and the Passover service follows a strict order of rituals re-creating the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt. These include drinking four glasses of wine, which recall the four acts of redemption God performs for the Israelites; dunking greens, which represent the lowly Israelites, into salt water, which symbolizes their tears; and breaking matzoh, bread baked without leavening because the Israelites were hurrying to flee Egypt. Other observances include tasting bitter herbs, representing the harshness of slavery; eating

haroset,

a mixture of apples, nuts, cinnamon, and wine, symbolizing the mortar used to build the pharaoh’s cities; and opening the door for Elijah, the prophet who is believed to herald the Messiah.

At the heart of the seder is a deeper message: History is not prerecorded. It is something we write ourselves. As Jonathan Sacks, the chief rabbi of Britain, put it: “We are not condemned endlessly to repeat the tragedies of the past. Not everywhere is an Egypt; not all politics are the exploitation of the many by the few; life is something other and more gracious than the pursuit of power.” The seder, which Sacks calls the “oldest surviving ritual in the Western world,”

calls on participants to do more than retell the story of the Exodus; they are to relive it themselves: “In every generation, a person should look upon himself as if he personally had come out of Egypt.” Passover is not a commemoration, it’s a call to action. Participants are summoned to become cocreators of a better world.

In America, Passover has long maintained a sacred time for Jews, in part because of its deep parallels with American history. In 1997 Rabbi David Geffen, an Atlanta native whose grandfather was asked in 1935 to guarantee that the secret formula for Coca-Cola was kosher (he insisted they remove glycerin made from beef tallow), compiled a survey of Passover traditions in the United States. As early as 1889, on the centennial of George Washington’s inauguration, anyone who bought ten pounds of matzoh got a free picture of the first president. The chief rabbi of New York composed a special prayer for Washington that year to be read in all American synagogues, many of which decorated their buildings with red, white, and blue bunting.

American wars, with their language of defending freedom, have provided many poignant settings for seders. During the Civil War, the Union Army actually provided matzoh to some regiments. Joseph Joel, a soldier from Cleveland, hosted a seder—which included lamb and a scavenged bitter herb—for twenty comrades in West Virginia in 1862. “The ceremonies were passing off very nicely,” he recalled, until the time came to eat the mysterious “weed.” “Each ate his portion, when horrors! The herb was very bitter and fiery like cayenne pepper, and excited our thirst to such a degree that we forgot the law authorizing us to drink only four cups and the consequence was that we drank up all the cider. Those that drank more freely became excited and one thought he was Moses, another Aaron and one had the audacity to call himself a pharaoh.”

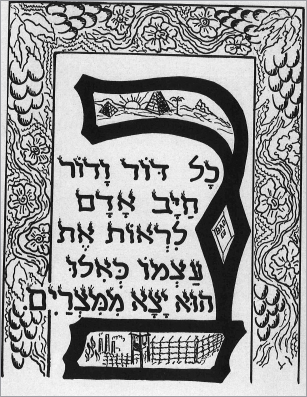

“In every generation one should regard oneself as though he had come out of Egypt.” The large letter “bet” contains the word “bad” and images of ancient Egypt at top and Nazi concentration camps at bottom. Drawing by Yosef Dov Sheinson from

A Survivors’ Haggadah. (Courtesy of The Jewish Publication Society)

In 1946, the Third United States Army hosted two “Survivors’ Seders” in Munich for four hundred people liberated from Nazi concentration camps. The front cover of their special

hagadah

declared, “We were slaves to Hitler in Germany,” and the introductory essay called Eisenhower “Moses the Liberator.” “They spoke of Pharaoh and the Egyptian bondage,” the text observed. “They spoke of slave labor and torture cities of Pithom and Rameses…. [But] Pharaoh and Egypt gave way to Hitler and Germany. Pithom and Rameses faded beneath fresh memories of Buchenwald and Dachau.”

During the civil rights movement, many American Jews paid tribute to blacks in their seders. In 1961, President and Mrs. Kennedy attended the seder of secretary of labor Arthur Goldberg and his wife, Dorothy, whose Passover meals for Washington’s elite were famous. The margin notes in Dorothy’s

hagadah

reminded her to mention that “one of the best descriptions of the exodus is the great Negro spiritual ‘Go Down, Moses,’” a clear paean to the marches going on across the South. By the 1970s, presidential seder attending had become more challenging. President Jimmy Carter and his wife attended a seder at the home of advisor Stuart Eizenstat. When the time came for Eizenstat to open the front door for Elijah, a Secret Service agent jumped up and stopped the two-thousand-year-old ritual, declaring it a security risk. Back and forth the two sides went, Eizenstat recalled, until “I was able to persuade him to permit me to open our rear door—the only time Elijah has been relegated to the back door in my home.” In 2009, Barack Obama hosted the first-ever seder in the White House, a milestone merging of African-American culture, Jewish ritual, and the American story.

From seder wineglasses in the 1920s that were molded like Lady Liberty to honor immigration to “matzohs of unity” for Soviet Jews during the Cold War to prayers against genocide in Darfur in 2008, Passover has always been a time for American Jews to renew the bond

between America’s struggles to fulfill its own ideals of liberty and the Israelites’ flight of freedom. The holiday has thrived in settings like war zones and Washington precisely because it is so universal to the American experience. The Passover story is America’s story.

At the start of my journey, I knew I would find the themes of Moses’ life in key moments in America’s past. But I did not anticipate the depth, breadth, and intensity of America’s attachment to the Exodus. I hadn’t known that the Pilgrims were so steeped in Mosaic language or that Americans took the words of Moses on a cracked state bell and turned it into an international symbol of liberty. I hadn’t known that Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams proposed Moses for America’s seal, or that Washington was eulogized as the American Moses. I hadn’t realized how deeply Moses motivated the slaves or how richly he echoed at Gettysburg. I was surprised how directly he shaped the Statue of Liberty and how vividly he colored popular culture, from Cecil B. DeMille to Superman. And I was inspired that nearly every defining American leader—from Washington to Lincoln to Reagan—invoked the Moses story in times of crisis. From Christopher Columbus to Martin Luther King, from the age of Gutenberg to the era of Google, Moses helped shape the American dream. He is our true founding father. His face belongs on Mount Rushmore.

At the beginning, I hadn’t even thought to compare the influence of Moses in America with that of Jesus. The United States at its founding was essentially 100 percent Christian and is 80 percent Christian today. Of course, Jesus was influential in American life. But I found a real difference in their public roles. As important as Jesus was to the faith and private lives of Americans, he seemed to have had far less influence than Moses during the great transformations of American history. The themes of Jesus’ life—love, charity,

the alleviation of poverty, forgiveness, spreading the good news of salvation, developing the kingdom of God—certainly echo throughout American history, but they would not make many lists of the defining characteristics of Americans. By contrast, the themes of Moses’ life—social mobility, reluctance to lead, standing up to authority, forming a persecuted people into a nation of laws, dreaming of reaching a promised land, coping with the disappointment of falling short—would be at home on any short list of America’s defining traits.

In the early 2000s, two books tracing the history of Jesus in the United States were published:

Jesus in America

by Richard W. Fox and

American Jesus

by Stephen Prothero. Both authors, distinguished scholars, trace Americans’ changing attitudes toward Jesus and show how his presence evolved, from his near absence during the Revolution to a more approachable, feminized savior in the nineteenth century, to a manly, aggressive redeemer in the early twentieth century, to a friendly superstar in the celebrity culture of the twenty-first century. “In a country divided by race, ethnicity, gender, class, and religion, Jesus functions as a common cultural coin,” wrote Prothero of Boston University. “Though by most accounts he never set foot in the United States, he has commanded more attention and mobilized more resources than George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., combined.”

My conclusions about Moses are somewhat different. Not only did Americans’ attitude toward him evolve, not only did he provide a common cultural language, and not only did he command attention and mobilize resources, Moses actually helped shape American history and values, helped define the American dream, and helped create America. Moses was more important to the Puritans, more meaningful in the Revolution, more impactful during the Civil War, and more

inspiring to the immigrant rights, civil rights, and women’s rights movements of the last century than Jesus. Beyond that, Moses had more influence on American history than any other figure from the Bible or antiquity. Also, while certain intellectuals might have had a greater impact on particular periods of American life, no single thinker has had more sustained influence on American history over a longer period than Moses—and that includes Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Hobbes, Montesquieu, Marx, Darwin, Freud, and Einstein.

In addition, my own view of America was completely transformed by my travels. Like many people, I carried around in my head certain narrative frameworks through which I view the main story lines of American history. These involved the interplay between North and South, black and white, East and West, immigrant and native, urban and rural, rich and poor, left and right, and so on. Now I have a completely new frame—not only one I didn’t know before but one I’d never even heard before. The Exodus. Discovering how much the biblical narrative of the Israelites has colored the vision and informed the values of twenty generations of Americans and their leaders was like discovering a new front door to a house I’d lived in all my life. You can’t understand American history, I now believe, without understanding Moses. He is a looking glass into our soul.

But why?

The answer comes down to three themes. The first is the courage to escape oppression and seek the Promised Land. As the Protestant theologian Walter Brueggemann has written, Moses’ influence on Western thought stems from his role as the prophet who sought to evoke in Israel a commitment to improve the world. The prophet’s vocation, Brueggemann wrote, is “to keep alive the ministry of imagination, to keep on conjuring and proposing alternative futures to the single one the king wants to urge as the only thinkable one.”

That is Moses’ gift and his legacy: He proposes an alternative reality to the one we face at any given moment. He suggests that there is something better than the mundane, the enslaved, the second-best, the compromised. He encourages people to be restless, and revolutionary. Brueggemann noted that a prophet does not ask if the dream can be implemented. As countless American visionaries have insisted, imagination must come before implementation. Perhaps Americans’ chief debt to Moses is his message that we should never settle for the status quo, and always aspire to what Thoreau termed the “true America.” In the words of W. E. B. Du Bois, “Not America, but what America might be—the Real America.” As Langston Hughes put it: