America's Prophet (23 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

“John Derek. Tested for the part of Joshua. He knows nothing about the Bible.”

“Audrey Hepburn. Not pretty but a very cute personality. Very expressive eyes. Gives the impression of being smaller on screen than she is.” DeMille tested Hepburn for Nefretiri, Moses’ love interest, but her breasts were deemed too small for the voluptuous costumes, and the part went to Anne Baxter.

DeMille’s analysis of Charlton Heston was especially tough. “Has a sinister quality,” he wrote in 1950. “He’s sincere. You believe him. But he’s not attractive.” He goes on, “Find out if he has some humor. Everything I’ve seen him in he’s dour. He has a funny way of speaking. It’s an artificial way.”

“When Heston did get the part of Moses,” Helen said, “DeMille invited him up to the house every Sunday for acting lessons. DeMille would put pebbles in his mouth to get him to talk naturally.”

On a nearby shelf, she pointed to another gem, a script from DeMille’s remake of

The Ten Commandments

in 1956. It opened with a manifesto: “All these things are as I have found them in the Holy Scriptures, the Glorious Koran, the ancient Hebrew writing, and in the annals of modern discovery. CBM.” To give his film the veneer of authenticity, DeMille had his personal researcher, Henry Noerdlinger, spend years reading all the midrashic retellings of Moses, as well as every known volume of biblical archaeology. Noerdlinger’s research was later published, which gave DeMille great pride, though the seventy-three-year-old showman never seemed to hesitate about tossing out the findings when it suited him. Noerdlinger reported, for instance, that camels had not been domesticated at the time of Moses, but DeMille insisted that the audience expected camels, so camels he gave them.

Even more unusual, DeMille poured his research, along with plentiful quotes from the Bible, into a handful of scripts for close

aides. The result, never published, is one of the most ornate depictions of the Moses story I’ve ever seen. Each line of dialogue is accompanied by an individual frame of celluloid from the final film. When the voice of God calls out from the burning bush, the Bible simply says Moses hid his face, “for he was afraid to look at God.” DeMille, the master of overstatement, thought this wasn’t enough, so he flushed out the scene. “Moses makes a subconscious move to comply with the order but is awe-smitten. Eyes look down. And beads of sweat start from his brow. The scene subfuses with light of unearthly, vibrant quality. From within the corona of flame, spectrum rays are pulsating like an Aurora Borealis.”

The scene in which Moses parts the Red Sea is particularly vivid:

As the thunderheads grapple in the darkened sky, Moses raises his staff and turns to the turbulent sea. He stretches his rod above the waters, the voice of God speaking through him. “Behold His mighty hand!”…From the darkening sky comes the rumbling howl of a hurricane that strains the robe against Moses’ body. A second seething rush of air screams over the surface of the waters. The two cloudbanks collide with a thundercrash in a titanic impact that fuses them for instants before detonating downward in a maelstrom’s swirl.

That DeMille recorded these descriptions in a handful of private scripts suggests how committed he was to the Bible. He was using the power of cinema to reach large numbers of people who otherwise might not read the text. In church, his mother once said, his father could reach thousands of souls; in theater, hundreds of thousands; then a new form came along, “the motion picture, and I was able to reach hundreds of millions.”

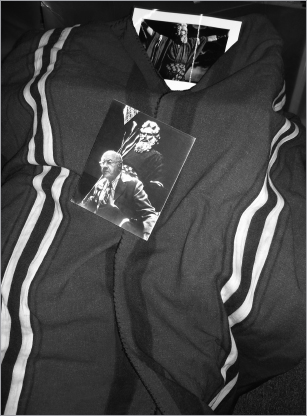

Moses’ robe, worn by Charlton Heston in

The Ten Commandments,

including photographs of Heston splitting the Red Sea and Heston with director Cecil B. DeMille; the actor wears the robe in both. From the private collection of the Cecil B. DeMille Estate.

(Photograph courtesy of the author’s collection)

The last item Helen pulled from a shelf was a white box labeled “MOSES ROBE.” She opened the top as if it contained the Shroud of Turin. Inside was a museum report: “Overall clean excellent condition. Five intact tassels on hems, slightly matted, cotton tule stripes have been intentionally distressed, spot of black paint 22.5 inches from hem.” She unfolded the tissue paper and there was the burnt-orange robe with the vertical tan-and-brown stripes that Charlton Heston wore during the splitting of the Red Sea. The fabric had the burlappy feel of African mudcloth, and Noerdlinger’s research claimed the colors, white, black, and red, represented the Levite tribe, a detail not in the Bible. More likely DeMille chose the color because he knew darker colors would prevent the actors from blending into the sandy background.

At Helen’s suggestion I slid it on and found that at nearly six feet two, I was roughly Heston’s height. I resisted the temptation to spread my arms. My first impression was how well made the garment was. Fifty years later, it seemed ready for another grueling desert shoot. But my next impression was how quaint it was. DeMille may have boasted that every aspect of his film had been taken from ancient sources, but those sources were written over a millennium after Moses would have lived. The pretense of accuracy seems very Hollywood, but it also reflects the self-confidence and reliance on science that dominated America in the postwar era. DeMille didn’t believe he was making an interpretation of Moses’ life. He was making

the definitive account

. In the process he made a film that says more about America in the 1950s than it does about Egypt in the 1250s

B.C.E

.

THE IDEA THAT

Moses might help promote American ideals abroad did not begin with Hollywood. In the country’s formative

centuries, Moses was most often used as a role model for outsiders’ claims that they were escaping oppression and trying to create a new Promised Land. The Pilgrims, patriots, and slaves all used Moses in this way. But by the twentieth century, America began to change, and so did Moses’ role in the country’s imagination. As the country secured its strength at home, it increasingly began to project its influence abroad. Once again, Moses provided the narrative.

As early as 1850, Herman Melville called Americans “the Israel of our time; we bear the ark of Liberties of the world.” During World War I, Woodrow Wilson was hailed as Moses for his efforts to covenant the world under the League of Nations. Later Franklin Roosevelt was compared to Moses for leading Europe out of fascism.

Using Moses as a counterweight to Nazi Germany was particularly popular during World War II. Thomas Mann wrote a novel about Moses in 1943 as part of the anthology

The Ten Commandments: Ten Short Novels of Hitler’s War Against the Moral Code

. The anthology’s editor hoped to turn it into a film modeled on DeMille’s 1923

Ten Commandments

. A similar idea colored

Brigham Young,

the 1940 biopic of the Mormon leader known as “America’s Moses.” The connections between Moses and Mormonism run deep. The religion was founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith, a Mason who published

The Book of Mormon

and other scriptures that he claimed augmented the Bible. A central feature of Smith’s theology describes how Jesus visited the Americas after his resurrection and preached to descendants of the Lost Tribes. Smith had a fascination with Moses and stated that the Hebrew prophet appeared to him in 1836.

Brigham Young

tells the story of Smith’s mob assassination in 1844, after which Young leads an exodus of Mormons from Illinois to the Great Salt Lake. To help get the controversial film made, producers played up the parallels between Mormons in America

and Jews in Germany. As one of the filmmakers put it,

Brigham Young

could be “an antidote to the increased spread of fascism and anti-Semitism.” The film repeatedly links Mormons with the Israelites. Smith’s dying words anticipate a deliverer who will “lead my people as Moses led the children of Israel across the wilderness.” Young later declares of the exodus, “I doubt that there’s been anything equal to this since the children of Israel set out across the Red Sea.” And when the people complain about the barrenness of Utah, Young says, “I don’t claim to be a Moses, but I say to you just what he said to the sons of Levi, ‘Who is on the Lord’s side? Let him come unto me.’” The quote is from Moses after he discovers the golden calf.

The most influential use of Moses as pro-American propagandist during these years may be the least known. It comes from two bookish Jews in Cleveland, Ohio, who in 1938 channeled their religious anxieties into a cartoon character they modeled partly on the superhero of the Torah. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were born twelve blocks from each other in Cleveland. They met while working on their high school newspaper and shared a passion for science fiction. In 1938, a five-year-old proposal they had submitted under the Gentile-sounding pseudonym Bernard J. Kenton was chosen as the cover feature of a new series,

Action Comics.

The first cover showed a man with bulging muscles, blue tights, and a red cape lifting a wrecked car to save a passenger. The story followed a klutzy reporter with spectacles who led a double life; he used X-ray vision and extrahuman strength to fight for social justice. The character’s name was Superman.

Superman drew from many sources, including Greek mythology, Arthurian legend, and the science fiction of Edgar Rice Burroughs. But many of its principal themes are drawn from the Hebrew Bible, and its backstory is taken almost point by point from Moses. Just as

Moses was born into a world in which his people faced annihilation, Superman is born on the planet Krypton, which is facing extinction. Just as baby Moses is put into a small basket and floated down the Nile by his mother, baby Superman is placed into a small rocket ship by his mother and father and launched into space. Just as Moses is rescued by the daughter of the pharaoh, Superman is rescued by Jonathan and Martha Kent in a midwestern cornfield. Like Moses, Superman is raised in an alien environment where he has to conceal his true identity. Just as Moses receives a calling from God to use his powers to liberate his people from tyranny, Superman receives a calling from his father to use his great strength “to assist humanity.”

Even Superman’s name reflects his creators’ biblical knowledge. Moses is the leader of Israel, or

Yisra-el

in Hebrew, commonly translated as “one who strives with God.” The name comes from Genesis 32 in which Jacob wrestles with a mysterious man who represents God.

El

was a common name for God in the ancient Near East and appears in the Bible in names like

Elohim

and

El Shaddai

. Superman’s original name on Krypton was Kal-El, or “Swift God” in Hebrew. His father’s name was Jor-El. Superman was clearly drawn as a modern-day god.

To help understand what all these connections meant, I went to see Simcha Weinstein. A thirty-two-year-old Orthodox rabbi from Manchester, England, Simcha grew up, by his own admission, short, shy, and pimply, not unlike the inventors of Superman. “I’d walk out of Hebrew school,” he explained, “take off my

kippah,

and shove it in my pocket. I was always scared of the big, non-Jewish kids on the corner. They’d ask my name, and instead of saying Weinstein, I’d say Jones or Smith.” He took solace in pop culture, especially comic books. “I related to the double identity. With Clark Kent, who’s weak and unsure of himself; with Peter Parker, aka Spider-Man, because

he can’t get a job or get the girl. Yet they can still save the world. On the one hand, you read all these stories about Moses and the chosen people, and on the other hand, you walk down the street and there’s a swastika on the synagogue and everyone’s bashing Israel.” Simcha moved to America, donned the black hat of Hasidism, and eventually wrote a book,

Up, Up, and Oy Vey!,

about how Jewish culture shaped the comic-book superhero.

“Today,

Action Comics

number one with Superman on the cover sells for over a million dollars,” said Weinstein, who lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two children. “But in those days it was a joke. For Jewish artists, getting into advertising was hard, getting into high-brow art was harder. But with comic books, the barriers to entry were nothing. So people like Siegel and Shuster started drawing these superheroes who were metaphors for their own lives.”

A similar thing happened in the film business. As Neal Gabler described in

An Empire of Their Own,

many of the pioneering moguls of Hollywood, including the founders of Universal, Paramount, Warner Bros., Fox, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, came from eastern European Jewish immigrant families. Beyond their religious background, what united these men was a desire to reject the oppression they left behind and embrace their new Promised Land. Assimilation was hardly new, Gabler wrote, “but something drove the young Hollywood Jews to a ferocious, even pathological, embrace of America. Something drove them to deny whatever they had been before settling here.” A similar dynamic took hold in comic books, where a small coterie of Jewish artists created Superman, Batman, the Green Lantern, Captain America, Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk, the Fantastic Four, and the X-Men.