America's Prophet (15 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

Few people I met understood this message better than Joan. As we were leaving, I asked her how her experience affected her.

“I never thought of myself as a religious person,” she said. “But once I got started, so many things I call miracles happened. In the first week, a truck driver, a white guy named Al, heard about my walk and pulled his eighteen-wheeler to the side of the road and was waiting for me. He said, ‘Mrs. Southgate, I just had to stop and say thank you. I think we have not done a good job of telling our children the stories.’ And then he said, ‘Do you mind if we pray?’ At first I thought, ‘Oh, he’s one of those fanatics,’ but the way he spoke was exactly as I would have spoken. I kept thinking of all these people on the roads who are just like us.

“There’s an African word,

sankofa,

” Joan continued, “that kept coming back to me during my walk. It means ‘go back and fetch it.’ Step back into the past and bring it to the present, so we don’t make the same mistakes. That’s what I learned on the Underground Railroad. We have to keep our past alive.”

THE WAR BETWEEN THE MOSESES

I

’

M LOST. I’M

searching for a white Victorian mansion on a hill overlooking Cincinnati. In the early years of American expansion, the house was a meeting point of East and West. In the buildup to the Civil War, it was a battleground of North and South. Today it’s nearly impossible to find, trapped in a sad sprawl of abandoned car dealerships, one-room BBQ joints, and urban blight.

Between 1820 and 1840, Cincinnati was the fastest-growing city in the world and one of five American cities with a population of more than 25,000. It was also the City of Many Nicknames. “Porkopolis” was a teeming mix of swine and swindle, where southern pork farmers sold their pigs to northern packers. “The London of the West” was a fierce testing ground for American religious freedoms, where Protestants fought vicious battles with Catholics and where Jews and Mormons made early stands for legitimacy. And “the Queen City” was a

tinderbox in the battle over slavery. Though nominally free, the city depended for its wealth on selling goods—including humans—from plantations in Kentucky. Cincinnati stood in the North, the saying went, but it faced the South.

All of these reasons helped make the Victorian mansion a center of intrigue. In the 1830s, the fledgling Lane Theological Seminary built the “peculiarly pleasant” house on a choice perch above town in an attempt to lure the most famous preacher in America to become its president. Lyman Beecher was the last great oak of New England Puritanism and a deacon of Old World oratory. As one contemporary recalled, “No American, except Benjamin Franklin, has given utterance to so many pungent, wise, sentences as Lyman Beecher.” He was also the father of thirteen children, two of whom became central players in the dominant showdown of American identity.

The first of Beecher’s prominent offspring was Harriet, his fifth child. Her novel

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

was so influential in shaping public opinion that Abraham Lincoln was said to have remarked on meeting Harriet in 1862, “So you’re the woman who wrote the book that started this great war!” The second of Beecher’s progeny to dominate the era was his ninth child, Henry Ward, who by 1860 had become the most important preacher in the country and, according to a biographer, “the most famous man in America.” Grateful for Henry’s role in helping turn the English against the South, Lincoln asked the portly preacher to give a sermon at the raising of the Union flag at Fort Sumter in April 1865, the symbolic end of the war. “Had it had not been for Beecher,” Lincoln said, “there would have been no flag to raise.”

Harriet and Henry were reared by their Calvinist father in the most storied Christian family of the century. They shared a love of fireside debate, a passion for Scripture, and an interest in mining one

biblical narrative to support abolition. A chief tension in nineteenth-century America was that half the country disagreed with the Beechers but used the same Bible, the same narrative, and the same central figure to argue the opposite case.

Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, photograph, c. 1868.

(Courtesy Harriet Beecher Stowe Center)

The Civil War was a battle between North and South, between Union and states’ rights, between slavery and emancipation. But it

was also an exegetical battle over who controlled the Bible. The least understood dimension in the War Between the States is that it was also a War Between the Moseses. Both North and South claimed that Moses was on their side. Southerners pointed out that the Five Books of Moses are full of laws, given by God on Sinai, that govern the ownership of slaves. Why would God spend so much time regulating an institution he disapproved of? The Northern case was more indirect. It drew on the larger themes of the Bible that all humans are created in God’s image, and stressed the triumph of the Exodus in which Moses leads the Israelites out of bondage. Why would God free his people from slavery only to allow them to enslave others?

When one side eventually lost the War Between the Moseses, the result was the most severe theological crisis the United States had ever seen. It took perhaps America’s most Bible-quoting president, Abraham Lincoln, to try to salve the wound. In doing so, he was hailed as America’s greatest Moses.

AS A MARK

of the world it helped create, the Stowe House sits on Gilbert Avenue between Lincoln Avenue and Beecher Street, just a block from Martin Luther King Drive, in the once heyday thriving community of Walnut Hills. The stately home is hidden under broad trees at the top of a slope that in its heyday brimmed with locust trees, rosebushes, and honeysuckle. On this day, as on most, it’s empty.

“The Beechers moved here in 1833,” explained Barbara Furr, the chief docent. An African American, Barbara is not much taller than Harriet, but she’s more feisty than the famed introvert. “Harriet moved out in 1836 when she married Calvin Stowe, but came back a few months later to give birth to their twins. Calvin was a biblical

scholar and was off collecting books in Europe. Can you imagine? He could have took her! He just didn’t want to spend all that money on a woman.”

But soon that woman began earning more money than everyone else in her family combined.

The “first family of the Northern cause” were agents of change when nearly everything in America was changing. Historian Gordon Wood likens the decades after the Revolutionary era to the bursting of a dam, when society exploded in an unprecedented eruption of population and ideas. By the early 1800s, he writes, America had emerged as “the most egalitarian, most materialistic, most individualistic society” in history. Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, said Americans were awash in selfishness, and he lamented that he felt “like a stranger” in his native land, “a bebanked, a bewhiskied, and a bedollared” place. Like many, Rush believed the only force strong enough to hold together the fracturing country was religion. As Lyman Beecher put it, religion was “the central attraction” that could cure the country’s political disarray.

Rush and Beecher got their wish. Religion boomed in nineteenth-century America, but it was not the top-down Calvinism of Beecher’s youth. Instead, it was closer to the populist model introduced by the Great Awakening, in which believers could experience a “new birth” and form their own relationship with God. The Enlightenment notion of universal rights, so crucial to American politics, became equally central to religion as Americans decided they had the right to interpret the Bible for themselves. The result was the Second Great Awakening, the most sweeping wave of voluntary religious conversions since the Reformation. In 1780, one in fifteen Americans belonged to a Protestant church; by 1835, the ratio had nearly doubled to one in eight. By 1850, 40 percent of Americans defined themselves as evangelical Christians.

Baptists and Methodists, denominations that held that individuals were responsible for their own salvation, benefited the most. The number of Baptist churches grew fifteenfold during these years; the number of Methodist churches twice that. The old Puritans, meanwhile, dropped from 20 percent of the population to 4. The impact on American life was profound. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed in the 1830s, America was “the place in the world where the Christian religion has most preserved genuine powers over souls.”

But American society was also “the most enlightened and most free,” Tocqueville said. By midcentury, Americans realized that the idea Jefferson called the Constitution’s “wall of separation” between church and state actually

spurred

religious growth rather than killing it. The First Amendment’s ban on the “establishment of religion” ensured that federal money would not be directed to religious institutions. Most European countries still funded state churches, and while some American states continued this practice into the 1830s, American churches were ultimately cut off from public funds. The change forced churches to compete more openly in the marketplace of ideas and to work more feverishly to attract new members. The pressure to become more user-friendly became one of the hallmarks of American religion and one of the primary reasons religion continued to thrive in the United States, long after state-sponsored churches elsewhere began to atrophy.

And just as political freedom enhanced religious freedom, religion began to reshape politics. The first national political convention was convened in 1831, for example, by a onetime evangelical society that called on many of its revivalist techniques. The vernacular of American political campaigns—the parades, the tents, the rousing speeches, the passing of collection plates—was lifted from this era’s barnstorming evangelical preachers. The government and the churches are “mutual friends,” wrote a minister in 1831. The church

simply asks for protection, and in return the state receives “the immense moral influence of the church.”

Few men embodied this symbiotic relationship more than Lyman Beecher, a pioneer in the wave of Christian volunteer societies that swept America with a spirit of do-goodism. Beecher focused on such issues as temperance, literacy, and Sunday schools. His most successful effort was the American Bible Society, which he helped found in 1816. The society’s goal was to use up-to-date printing techniques and distribution to counteract the wave of secular publications that were distracting Americans from their Bibles. The group’s ambition was to have “a Bible in every household,” and it came remarkably close. Capitalizing on the new printing technique of stereotyping, using lead plates to make facsimiles that could be reproduced more efficiently, the society generated an outpouring of Scripture. In 1829 alone, it printed 360,000 Bibles; in 1830, the number rose to 500,000. By the 1860s, the society was printing more than 1 million copies a year, for a population of 31 million. Americans may have been a People of the Book before, but now they could actually

own

the Book.

But the biggest movement Beecher joined was carrying the Protestant ideal of a new American Israel across the mountains into the wilderness of the West. Beecher’s original objective in moving to Ohio was to “evangelize the world” and save the region from Catholicism. “The religious and political destiny of our nation is to be decided in the West,” he said in a fiery 1835 speech. He and others echoed many of the themes from the Pilgrims and the First Great Awakening. And once more, they relied on the language of the Exodus.

In 1784, John Filson, a Pennsylvania schoolmaster, returned from two years across the Appalachians and published

The Discovery, Settlement and Present State of Kentucke,

a recruiting booklet designed to lure people to the region. Filson called the territory “the land of promise,

flowing with milk and honey,” where “you shall eat bread without scarceness and not lack any thing.” His account ended with a dramatization of a real yet undistinguished trader named Daniel Boone, which helped turn the Revolutionary War veteran into the archetypal hero of the American frontier. Since Boone was a man of few words, Filson flushed out his “autobiography” with elaborate fictionalizations

drawn from sources ranging from Roman to Romantic. But many of the characteristics Filson gave to Boone were modeled on a figure known for venturing into the wilderness.

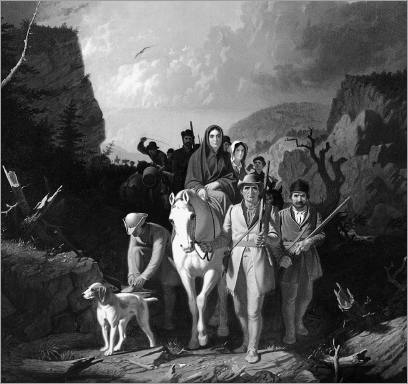

George Caleb Bingham’s

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers Through the Cumberland Gap,

1851–52. Oil on canvas, 36½ x 50¼". Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Gift of Nathaniel Phillips, 1890.

(Courtesy of The Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum)

Like Moses, Daniel Boone leaves his family for the howling wilderness. Like Moses, he arrives traumatized but is cleansed and transformed by his immersion in nature. Like Moses, he experiences an encounter with Providence. Like Moses, he climbs a summit and overlooks an even greater paradise ahead of him. And like Moses, Boone returns to summon those left behind to migrate into the untamed territory and transform it into a new Eden.

There are differences in the two narratives, of course, but in the biblicized America of the nineteenth century, many recognized Daniel Boone as “the Moses of the West.” In 1851, George Caleb Bingham painted

Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers Through the Cumberland Gap,

depicting a Moses-like Boone leading an exodus through the parted Appalachian mountains with a shaft of light in front, a trail of clouds behind, and a white horse by his side. Even the phrase that encapsulated this period, “manifest destiny,” evoked for literate Americans the biblical calling for God’s chosen people to settle the Promised Land. Beginning with the Puritans, the world was often referred to as God’s “manifestation” and history as God’s “destiny.” Manifest destiny was another way of saying that God had chosen Anglo-Americans to convert the land for him—no matter who got misplaced. In the same way that colonizing America was viewed by many participants as a reenactment of the Exodus, many settlers heading west saw themselves as reliving the Israelites’ flight into the wilderness to create a new American Israel.