A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (36 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

Figure 8-17. Because of the ambiguity shown in Figure 8-16, a diminished 7th chord can resolve in any of four different directions. Dropping any note in the chord by a half-step creates a dominant, which can then move to its own tonic.

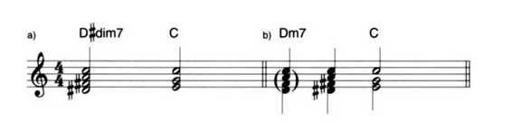

Figure 8-18. A diminished 7th chord can resolve through chromatic movement of the lower voices (a). One way to look at this progression is that the diminished chord is the result of chromatic movement in the lower voices from a llm7 chord, as in (b). This chord may not actually be present in the progression, however.

Figure 8-19. Instead of resolving a diminished 7th chord, as in Figure 8-17 or 8-18, we can let it slide downward chromatically.

Another very natural way to resolve a diminished 7th chord is by moving its lowest two voices upward by a half-step to form a major triad in first inversion. This resolution is shown in Figure 8-18a. If you analyze this chord as a D769 with no root, the resolution to C major may not seem very sensible. A better theoretical explanation for why it sounds good is that the D# and F# are passing tones, as in Figure 8-18b.

Still another way to use diminished 7th chords in a progression is to slide downward chromatically, as in Figure 8-19. This sounds very smooth and natural, because each of the voices is moving by half-steps (for more on voice leading, see below), but there's no way to know how the progression will resolve. We could be modulating to any key at all.

PEDAL TONES

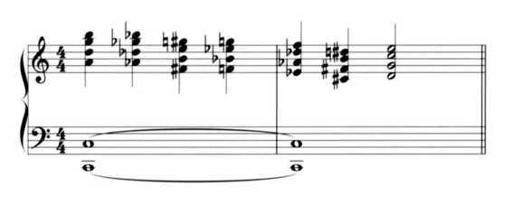

Instead of branching off to an entirely new key, a progression can remain obsessively anchored in one key, even when you might expect it to move. The device with which this is done is called a pedal tone, or simply a pedal. The term comes from pipe organ music: A pipe organ is equipped with a bank of footpedals, which are connected to low-pitched pipes. For the most part, the pedals are used to play slower-moving lines, which makes sense, as our feet are not our most agile appendages. A dramatic effect is achieved in organ writing by jamming a foot down on one note (usually the tonic or dominant) and keeping it there while the hands play a moving passage above the sustained pedal tone. This is often done at the climax of a piece. The idea is illustrated in Figure 8-20.

The ear will accept almost any dissonance as harmonically coherent when it's part of a pedal-tone passage, because the pedal is strong enough to guide the ear toward the expected harmonic resolution. The chromatically moving chords in Figure 8-21 provide an example of this.

Figure 8-20. A vaguely jazzy progression over a pedal tone.

Figure 8-2 1. Dissonances can work well when an unmoving pedal provides a foundation. The ear tends to interpret the upper notes as passing tones rather than as a free-standing chord progression.

VOICE LEADING

For the most part, in this book we've been looking at chords as essentially vertical objects - groups of notes that are all played at once. But music is a timebased art. In any piece of music, sonorities follow one another in a horizontal manner. When we start connecting chords to one another to form progressions, it's not enough to think about which chord follows or precedes which other chord. The question of how we move from one chord to another becomes important.

In Chapter One, we introduced the idea that a chord is made up of separate voices, each of which sounds exactly one note in the chord. When the progression calls for a new chord, each voice in the first chords must do one of four things: It can play the same note as before (if the two chords contain a suitable common tone). It can move upward to a new note. It can drop downward to a new note. Or, if the new chord contains more or fewer voices than the old chord, a voice can stop or start.

The activity of the various voices is called voice leading. In the study of voice leading, a chord progression is viewed not as a series of vertical sonorities but as a group of independently moving horizontal lines. We can look, first, at how each voice moves on its own, and second, at how the various voices are moving during transitions from one chord to another. For example, are they all moving upward, or are some moving upward while others move downward?

The earliest music in the Western tradition (written during the Middle Ages) was choral music, and the vertical sonorities employed (chords, in other words) were all a result of the movement of actual voices. Music theorists in those days developed some fairly elaborate rules about voice leading - rules that are, though not entirely irrelevant today, of marginal value in pop music arrangements. Most books on classical harmony theory provide extensive information on voice leading as it was practiced by Bach and other composers in the ensuing 150 years.

In such books, you'll encounter some specific rules. Parallel 5ths, for instance - the simultaneous movement of two voices from one 5th interval to another, as in Figure 8-4 - are explicitly forbidden. At least, they're forbidden for students. Composers from this period did occasionally use parallel 5ths, though they usually avoided them. Theorists, however, sometimes try to explain away the parallel 5ths, or make excuses for them. In Piston's Harmony, for instance, it's asserted that a passage in Beethoven's Symphony No. 6 that contains parallel 5ths "can probably be attributed to inadvertence" In other words, Beethoven didn't notice the parallel 5ths; if he'd noticed them, he'd have fixed the "mistake" The tendency to prefer theoretical correctness to actual scores written by actual composers is perhaps more common in the academic world than it ought to be. I'm more inclined to give Beethoven the benefit of the doubt. I suspect he used the parallel 5ths on purpose, because that was the sound he wanted at that particular spot. In case you're curious, I've reproduced the passage in question in Figure 8-22.

Academic fussing aside, it's probably worthwhile to know the "rules" for classical voice leading. For one thing, knowing them will help you appreciate the vast body of music written by European composers in the 18th and 19th centuries, most of which relies on these rules in almost every measure. In addition, once you know the rules you can violate them intentionally when you want to do so, rather than stumbling into awkward voice leading by accident. Parallel unisons, octaves, and 5ths were avoided because they sounded too strong. They gave an undue weight to the movement from one chord to the next, while tending to obscure the separate movement of the individual voices.

Figure 8-22. If you take music theory in college, you won't be allowed to use parallel 5ths, but Beethoven did it in this well-known passage, which appears near the beginning of the first movement of his Symphony No. 6. Between bars 3 and 4, the top voice moves downward from C to G while the bottom voice moves down from F to C.

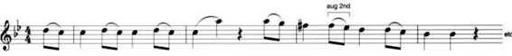

The movement of voices by augmented and diminished intervals was also avoided. This was because the principles of voice leading were developed at a time when actual voices (human singers) were being employed, and augmented and diminished intervals are difficult to sing. Here again, this "rule" was occasionally violated, for good reason and with good effect, by composers of the period (see Figure 8-23).

Figure 8-23. Using augmented or diminished intervals in the movement of a voice is often considered a bad idea - but Mozart got away with it in the first movement of his Symphony No. 40.

One important question to ask about the voice leading in a passage is whether the voices move smoothly (that is, using small intervals), or whether there are a lot of large leaps. The technical term for motion that includes leaps of a 4th or more is disjunct motion. Some theorists consider any movement other than by step to be disjunct. Figure 8-24 may give you an idea of how the choice of smooth or disjunct voice leading can affect the sound of a progression. The two examples in this figure use the same progression (ignoring a couple of inversions). In the first example, the largest interval used by any voice in moving from chord to chord is a 3rd. In the second example, larger leaps, including some of more than an octave, are used.

Please note: I'm not saying the first example is better than the second one. The first one has a fairly dull, conventional sound, in fact, while the second one is arguably more interesting. All I'm saying is that when moving from chord to chord, it's important to think about whether you're using smooth or disjunct motion. If you use a series of chords that are connected with smooth voice leading and then suddenly switch to disjunct voice leading (or vice-versa), you'll be creating a contrast that may add a lot of interest to the passage.