A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (35 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

The general term used for key changes is modulation. (Sorry, synthesizer players: This isn't something you can do with your mod wheel.) When the perceived tonal center of the music - the note that's felt to be the tonic - changes, we say the music has modulated to a new key.

Modulation has been widely practiced since the earliest days of tonal music. In music of the Baroque and early Classical periods, most modulations were to closely related keys - from a major key to its relative minor, for example. More than any other composer, it was Beethoven who threw open the floodgates of modulation. Even in his early works he had few compunctions about modulating to almost any key at almost any time. Beethoven always had a strong sense of the original key of the piece he was writing, however. He used remote keys to introduce emotional contrasts.

In the Baroque and early Classical tradition, modulation from the tonic to the dominant and back again was a primary structural or organizational element. This type of modulation was used in thousands of pieces, and until you learn how to listen for it you'll be missing one of the most fundamental aspects of the music. Bach, for instance, wrote hundreds of two-part pieces in which the first part modulated to the dominant and the second part modulated back to the tonic. The main variant in his modulation formula was that a piece in a minor key might modulate either to the dominant or to the relative major.

In the late 18th century, this relatively simple structure of tonic-to-dominantto-tonic modulation evolved into sonata form. (If you'd like to know just about everything there is to know about sonata form, I can recommend Charles Rosen's masterful book Sonata Forms, which is published by Norton.) Briefly, a movement in sonata form usually has two main themes. At the beginning of the movement, the first theme is played in the key of the tonic. After a modulation, the second theme is played in the key of the dominant. At the end of the movement, the two themes are stated again - but this time, there's no modulation: The second theme stays in the key of the tonic.

The underlying emotional trajectory of such a piece is fairly clear: The music starts at a particular point (consider it "home"), travels to some other spot, and then returns home. A given movement is, on a psychological level, the equivalent of a journey. While the external forms used in today's popular music are entirely different from sonata form, the underlying emotional trajectory is exactly the same. The middle eight in an AABA jazz chorus or the bridge in a pop song is somewhat removed from the starting point - quite often by being in a different key, or at any rate using a different chord progression. The final A phrase or the final verse and chorus provides a return to the starting point, and rounds out the piece with a feeling of completion.

If you're curious how classical composers used modulation, there's no better way to learn than to study a few scores while listening to the CDs. Modulation is perhaps less important for pop musicians, but that doesn't mean it's a topic we can afford to ignore.

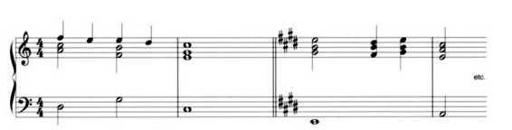

The simplest way to modulate is just to jump straight into the new key. This type of modulation is shown in Figure 8-11. How well it works in a given case will depend on the musical context. You'll note that the phrase in C major in this figure is an authentic cadence. Since a new phrase is about to begin in any case, listeners can more easily perceive the new tonal center without confusion if the previous phrase ends unambiguously. The fact that I've modulated from C major to E major, a relatively distant key, is also significant. This type of abrupt modulation wouldn't work nearly as well if the new key were F major or G major, because the ear would interpret the opening tonic chord of the new phrase as a subdominant or dominant in the key of C. The E major triad is not diatonic in the key of C, so it serves as an immediate signal that something new is happening harmonically, even before the V and IV chords confirm that E is a new tonic.

Figure 8-11. The simplest way to modulate: Finish a phrase in one key and then start the next phrase in the new key.

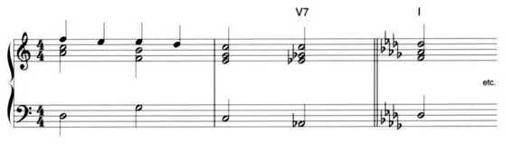

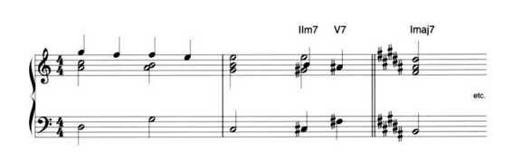

To make modulations less ambiguous, composers often prepare the modulation by preceding the tonic chord of the new key with its own dominant 7th, or even with a IIm7-V7 The modulation in Figure 8-12, for instance, is pretty much a cliche, but it's sometimes the right tool for the job, at least if you're writing in the mainstream ballad style popularized in the 1980s by Barry Manilow. The II-V modulations shown in Figures 8-13 and 8-14 are somewhat less hackneyed, and sound very natural: The ear is easily led to perceive the new key.

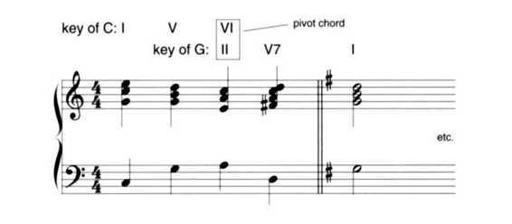

If you study modulation in the tradition of 19th-century classical music, you'll soon encounter the term pivot chord. A pivot chord is a chord that belongs to both the old key and the new one. A progression starts out in one key, hits the pivot chord, and pivots into the new key. The pivot chord is a sort of musical pun: It has two distinct meanings, depending on whether you're looking backward (at the old key) or forward (at the new one). The progression in Figure 8-15 uses a pivot chord (A minor) to modulate from the key of C major to the key of G major. This chord is found in both keys: It's the diatonic VI triad in C and the diatonic II triad in G.

Figure 8-12. Modulating up by a half-step is easy. Note that the tonic in the old key (C) becomes the leading tone in the new key. This gives the half-step modulation a lift. You can modulate to any key, however, by starting with a dominant 7th in the new key.

Figure 8-13. Introducing a new key with a 11m7-V7 progression.

The success or failure of the pivot-chord modulation technique depends on how ready the ear is to accept the new key. The modulation in Figure 8-15, for instance, wouldn't work well if the ear interpreted the G major triad in the second measure as a V chord in C. This is a particular difficulty when the two keys have such a close relationship. Classical composers sometimes went to considerable lengths to lead the ear astray, so that this particular modulation (upward by a perfect 5th from the tonic to the dominant) would sound natural. In the first movement of Mozart's Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, which is in sonata form, the modulation from the first theme in C major to the second theme in G major climaxes with a strong half-cadence on a D chord, the dominant of the new key. When the second theme begins with a resolution of this dominant, the new key is readily accepted by the ear as a tonic. Classical composers weren't always so punctilious about their modulations, however. Haydn often ended the first theme of a sonata-form movement on a half-cadence in the original key, and then simply launched the second theme on the same chord, which was now the tonic in the new key. This procedure may be less satisfying to modern listeners than it was in Haydn's day.

Figure 8-14. The 11m7-V7 progression allows us to modulate to almost any key. The first measure and a half here are the same as in Figure 8-13, but after the Imaj7 in C, we branch off in a different direction.

Figure 8-15. Modulation using a pivot chord. The A minor triad here is a VI chord in the key of C, and also a II chord in the key of G.

DIMINISHED 7TH CHORDS IN PROGRESSIONS

Some chords are even more ambiguous than the pivot chord in Figure 8-15. Take a look at the diminished 7th chord in Figure 8-16, for instance. It's not diatonic in any key, but what if we look at it as the upper voices of a 769 chord? This is the standard interpretation of a diminished 7th in classical harmony theory. This one diminished 7th chord can easily substitute for a dominant 7th in any of four keys: It can function as an F769, a D769, a B769, or an A6769, depending on which root we play. A classic way to use this ambiguity is to play a diminished 7th chord by itself and then lower one of its tones (any of them - it doesn't matter which) by a half-step to create a dominant 7th chord. Figure 8-17 shows how this type of progression works. A diminished 7th chord is thus an effective pivot for modulation to a variety of distant keys.

Figure 8-16. A diminished 7th chord (shown in the treble clef here) is harmonically ambiguous. The same four notes can form a 769 chord with any of four roots.