A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony (22 page)

Read A Player's Guide to Chords and Harmony Online

Authors: Jim Aikin

11TH CHORDS

Chords in which an 11th is stacked above the 9th are used from time to time, but they're less common than either 9th chords or 13th chords. There are two reasons for this. First, the natural 11th (which would be an F above a C root) interferes with our ability to hear the root of the chord, because it's the same note as the subdominant, which is a lower root. Also, it clashes with the major 3rd.

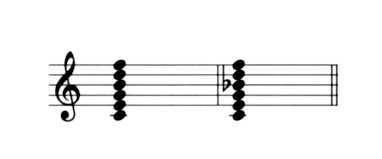

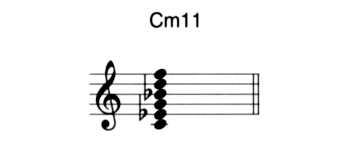

The voicings in Figure 6-6 show how out of place the natural 11th sounds against the major 3rd. These chords might be usable in some circumstances, but I'd tend to analyze them as bitonal (a G7 or B6 chord above a C triad) rather than as 11th chords. The natural 11th can be combined with a 3rd in only one chord I can think of offhand - the m l I chord, which is shown in Figure 6-7

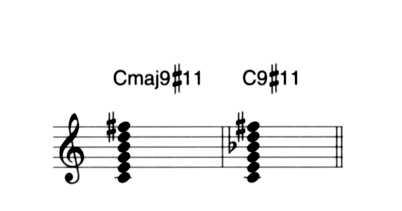

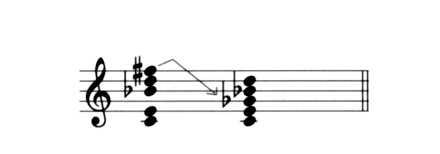

The sharp 11th (see Figure 6-8) is more useful. However, this note is the same as the flat 5th. So when the performer in search of a more open voicing drops the natural 5th, a #I I chord becomes indistinguishable from a 965 chord in which the 65 has been transposed up by an octave. Figure 6-9 illustrates this fact. So if the arranger calls for a #I I chord, it may be reasonable to assume the voicing is intended to include both a natural 5th and a #11. Alternatively, the arranger may assume the 5th will be dropped, and may be calling the note a #I I rather than a 65 to indicate that the 11th should be voiced at the top of the chord.

Figure 6-6. These 11th chords (Cmajl 1 and C11) are not very useful, because of the natural 11th. Raising the 11th, as in Figure 6-8, produces a more viable sound.

Figure 6-7. The natural 11th sounds good when combined with the minor 3rd and minor 7th.

Figure 6-8. The sharp 11th sounds good with both major-type and dominant-type chords.

Figure 6-9. If the 5th is omitted from the chord voicing, the #11 is functionally indistinguishable from a 65. Because of this, some arrangers will use a #11 in the chord symbol only when they also want the unaltered 5th to be included in the voicing.

Based on the rules for chord symbols given above, you can quickly deduce two things about chord symbols for 11th chords. First, any chord called an 11 also includes a 9th and a 7th. Second, when the 11 is sharped, it can't be mentioned immediately after the root. (Would a "C# 11 " be a C dominant chord with a # 11, or would it be a C# chord with a natural 11th?) Thus, strange as it may seem, a chord symbol for a chord containing a # 11 will always mention the 9th. If the 9th is flatted, as in C769#11, both the 7th and 9th need to be mentioned.

Some arrangers and music copyists, however, assume you're smart enough to know that except in a minor-type chord such as the ml1, the 11th is usually sharped. If you see a chord symbol like "C 11 " or "G 11 " in a score, it may be safe to assume that a #11 chord is meant. Or it may not (see the discussion of sus chords in "Other Chord Tones," below).

13TH CHORDS

The 13th falls on a modal scale step, so it can be either major or minor. There's no such thing as a diminished or augmented 13th, however. The diminished 13th would be the same note as the perfect 5th, and the augmented 13th would be the same note as the flat 7th. Some useful 13th chords are shown in Figure 6-10. Note that some interior notes are dropped from the voicings in this figure. These voicings may or may not be the most commonly used 13th chords, but they sound better to my ears than most of the alternatives.

Note the exception to rule 5 in the rules for chord symbols mentioned earlier in this chapter. The presence of a 13 in the symbol does not imply that the chord also contains an 11th (though it does imply the 7th and most likely the 9th). If the arranger wants an 11th to be part of the 13th chord, it will be mentioned in the chord chart. However, performers who regularly work from chord charts that include chords of this sort give themselves considerable latitude to interpret the symbols in ways that feel right at the moment. If you're playing with jazz players and see a 13 chord in a chart, you may or may not want to play a 9th along with the 13th. In fact, depending on what the soloist is doing at the moment, you might easily play an altered 9th or altered 5th, even though the chart doesn't call for it.

Figure 6-10. The 13th can be either major (as in the first, second, and fifth chords shown here) or minor (as in the third and fourth chords). The 13th is heard most often in dominant-type voicings (chords two through five) but also works nicely over a maj9#11.

VOICINGS USING 9THS, 11THS & 13THS

With 7th chords, we were able to create inversions rather freely, by placing any of the notes in the chord in the bass. In general, it's not practical to do this with the 9th, 11th, and 13th. When placed in the lowest voice, these notes tend to obscure the harmonic identity of the chord. Consider, for instance, the rather unfortunate inversions shown in Figure 6-11. If the higher notes of the stack are below the root, the chord tends not to be perceived as a 9th, 11th, or 13th chord but as something else, probably a bitonal voicing (see below). In other words, there's no such thing as a fourth, fifth, or sixth inversion of a 13th chord. However, we can continue to put the 3rd, 5th, or 7th in the bass, as before. Figure 6-12 shows a few voicings (mostly inversions) that sound pleasant and are easily identifiable. These chords have been revoiced in other ways as well: Sometimes one or two notes have been dropped, and one or more notes may have been shifted up or down by an octave.

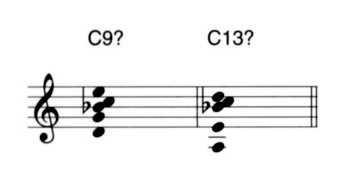

Figure 6-11. While the root, 3rd, 5th, or 7th of a chord can easily be used in the bass, it's not practical to put the 9th, 11th, or 13th in the bass, as doing so interferes with our ability to identify the root. The chord on the left has all of the notes of a C9, but because the 9th is in the bass, it doesn't sound much like a functional C chord. The chord on the right is even more awkward: The open 5th interval at the bottom leads the ear to expect some type of A chord, but this is contradicted by the B6 and D. This is not to say that voicings of this type are musically useless, however; see Figure 6-28.

If you're new to the idea of using extended voicings like these, the choice of notes may seem almost arbitrary: Couldn't we choose just about any combination of notes and call it a C chord? Yes and no. Your ear may suggest voicings to you that other players have ignored or rejected - and if it works for you, nobody can really tell you you're wrong. On the other hand, there are some guidelines you may find helpful to bear in mind.

First, chords that use both the major 3rd and natural 4th/11th of the scale are somewhat adventurous, though they can work well, as Figure 6-13 illustrates.

Second, you'll rarely hear a major 9th used in the same chord with a minor or augmented 9th. The sound is just too dissonant.

Third, the higher functions of an extended chord are usually placed higher in the voicing. Play the first two voicings in Figure 6-14 and you'll hear why. The second voicing sounds a bit muddy, or at least darker, because the 13th is voiced in the lower octave, while the 7th is more than an octave above it. In the third voicing in this figure, the 9th has also been moved down an octave, swapping places with the 3rd, and the voicing has become a bit unstable. At least one jazz pianist, Clare Fischer, has used the trick of dropping higher chord notes down to lower positions in this manner to give his chords a more mysterious flavor, but there are reasons why the practice is not the norm.