A History of the World in 100 Objects (80 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

The Great Wave

, like the other images in the series, was printed in at least 5,000 impressions, possibly as many as 8,000, and we know that in 1842 the price of a single sheet was officially fixed at 16 mon, the equivalent of a double helping of noodles. This was cheap, popular art; but when printed in such quantities, to exquisite technical standards, it could be highly profitable.

After Commodore Perry’s forced opening of the Japanese ports in 1853 and 1854, Japan resumed sustained contact with the outside world. It had learnt that no nation would be allowed to opt out of the global economic system. Japanese prints were exported in large numbers to Europe, where they were quickly discovered and celebrated by artists like Whistler, Van Gogh and Monet; the Japanese artist who had been so influenced by European prints now influenced the Europeans in return.

Japonisme

became a craze and was absorbed into the artistic traditions of Europe and America, influencing the fine and applied arts well into the twentieth century. In time, Japan followed the industrial, commercial West and was transformed in the process into an imperial economic power. Yet just as Constable’s

Haywain

, painted at roughly the same time, became the iconic image of a rural, pre-industrial England, so Hokusai’s

Great Wave

became – and in the modern imagination has remained – the emblem of a timeless Japan, reproduced on everything from textiles to tea cups.

Sudanese Slit Drum

AD

1850–1900

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, was one of the media stars of the First World War. The famous recruitment poster has him pointing straight at us in full uniform, finger in the foreground, handlebar moustache not far behind, with the words ‘Your country needs YOU’. By then Kitchener was already legendary as Kitchener of Khartoum, and this Central African wooden drum, which he captured and presented to Queen Victoria in 1898, just after his army had killed around 11,000 Sudanese soldiers in the Battle of Omdurman, is part of how he earned his title.

The biography of this slit drum, as it’s called, is a story of Sudan in the nineteenth century, when Ottoman Egypt, Britain and France all converged on this enormous Nile country which had long been divided between an African south, which practised traditional beliefs, and an Islamic north. It is another document of the enduring geopolitical fault-line around the Nile cataracts that we have encountered twice before: in the sphinx of Taharqo (

Chapter 22

) and the head of Augustus (

Chapter 35

). This drum is part of the history of indigenous African culture, of the East African slave trade centred on Khartoum, and of the European scramble for Africa at the end of the nineteenth century.

The slit drum began its life in Central Africa, in the region where Sudan and the Congo share a frontier, and it would have been part of the court orchestra of a powerful chief. It is in the shape of a short-horned buffalo or bush cow, about 270 centimetres (110 inches) long from nose to tail, and about 80 centimetres (30 inches) high, so about the size of a big calf with very short legs. The head is small, and the tail short – the bulk is concentrated entirely in the body, which has been hollowed out and has a narrow slit running across its back. The flanks of the drum have been carved to different thicknesses, so that a skilled drummer with a traditional drumstick can produce at least two tones and as many as four distinct pitches. It is made from a single piece of reddish African coralwood, a durable hardwood found in the forested areas of Central Africa and valued for making drums because it stands up well to repeated striking, maintains a constant tone and is resistant to termites.

The main function of the drum was music-making, marking community events such as births, deaths and feasts. Europeans dubbed these slit drums ‘talking drums’, because they were used to ‘speak’ to people at ceremonies and also to transmit messages over long distances – their sound could carry for miles – calling men either to a hunt or to war.

In the late nineteenth century, Sudan was a society under threat. European and Middle Eastern powers had long had a presence in Central Africa, drawn by its abundance of ivory and of slaves. For centuries slaves had been taken from southern Sudan and Central Africa, brought north to Egypt and then sold on across the Ottoman Empire; many Central African chiefs collaborated with the slave-traders to carry out joint raids on their enemies, selling the captives and sharing the proceeds. This intensified when the Egyptians took control of Sudan in the 1820s, and slave raiding and trading became one of the most profitable and powerful industries of the region. It was centralized by the Egyptian government in Khartoum, which by the late nineteenth century had become the greatest slave market in the world, servicing the whole of the Middle East. The writer Dominic Green assesses the situation:

The Egyptians had built up a substantial slave-trading empire, running from the fourth cataract of the Nile all the way down towards the northern shores of Lake Victoria. They had done this with some support from European governments, who were obviously concerned to get their hands on ivory as opposed to slaves, but were also concerned about the humanitarian aspect. The Egyptian khedives, the rulers of Egypt, played a double game, where they signed on to anti-slaving conventions pushed on them by the Europeans, and then pretty much continued to make money out of the slave trade.

The drum, which could have been seized as booty by slave-raiders or given by a local chief, almost certainly came to Khartoum as part of that trade. Once it arrived in Khartoum it began a new chapter of its life and was refashioned to take its place in this Islamic society. We can see this when we look at its sides: on each flank a long rectangle has been carved, running almost the whole length of the body, containing circles and geometric patterns – recognizably Islamic designs added by the new owners to protect against the evil eye. On one side the design is incised in the body of the wood, but on the other the wood has been cut away so that the design stands proud. This thinning would materially change the sound of the drum, evidence that although it might continue to be used for its original purpose of music-making or calling people to arms, it would now do so with a different voice. A musical instrument had become a trophy, and the new carvings were in fact branding, a statement of the north’s political dominance over Central Africa and of allegiance to Islam.

The drum had come to Khartoum at a critical moment in Sudanese history. The Egyptian occupation had brought with it many aspects of European technology and modernization, and a new kind of profoundly Islamic resistance was on the rise against it. Egypt was then technically part of the Islamic Ottoman Empire, but many Sudanese Muslims rejected what they saw as a very easy-going Islam that nevertheless brought with it political repression. In 1881 a religious and military leader arose: Muhammad Ahmad declared himself the

mahdi

– the one guided by God – and summoned an army to jihad, to reclaim Sudan from the lax, Europeanized Egyptians. It was called the Mahdist Revolt, and it was the first time in modern history that a self-consciously Islamic army took on the forces of imperialism. For a time, it swept all before it.

Britain had a fundamental strategic interest in a stable Egyptian government. The Suez Canal, built by the French and Egyptians in 1869, was an economic lifeline, the critical link between the Mediterranean and British India. But the building of the canal, other large-scale projects and chronic financial mismanagement by the Egyptian khedive had caused soaring national debt. When the Mahdist Revolt in Sudan added to the strain, Egypt looked as if it was going to founder in bankruptcy and civil war. In 1882, concerned for the security of the canal, the British moved to protect their national interests. They invaded, leaving an Egyptian government to rule with British advisers. Not long after, when the Mahdists besieged Khartoum, the British turned their attention to Sudan. As the power of the mahdi grew, the Egyptian government sent General Gordon to lead the Egyptian Army in the Sudan. His forces were cut off; Gordon was hacked to death in Khartoum and became a martyr in Britain. The Mahdists took over Sudan, as Dominic Green describes:

Gordon underwent one of those terrible Victorian deaths of being chopped to pieces and then reconstituted in marble statues and oil paintings all over Britain. Khartoum fell in January 1885, and once the outcry had subsided Sudan was pretty much forgotten about by the British until the mid 1890s. This was the time of the ‘scramble for Africa’; the British strategy was essentially to build a north–south connection from Cape, as they said, to Cairo. The French were working from east to west, or west to east, and an expedition under a Captain Marchand was despatched. It landed in West Africa and started staggering through the swamps towards the Nile. The British realized this and sent a force, a relatively small one, under Horatio Herbert Kitchener, and eventually in 1898, thirteen years after the siege, Kitchener’s army faced off against the Mahdist army.

On 2 September 1898 Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army destroyed the Mahdist forces at Omdurman – the battle included one of the last cavalry charges of the British Army, and one of the participants was the young Winston Churchill. On the Sudanese side about 11,000 died and 13,000 were wounded. The Anglo-Egyptian army lost under fifty men. It was a brutal result – justified by the British as protecting their regional interest against the French, but also as avenging Gordon’s death at Khartoum and putting an end to what they saw as the shameful slave trade.

The drum was found by Kitchener’s army near Khartoum after the Anglo-Egyptian reconquest of the city. Once again it was re-carved – or re-branded – to make a political statement: near the tail of the bush calf Kitchener added the emblem of the British Crown. It was then presented to Queen Victoria.

Sudan was ruled as an Anglo-Egyptian territory from 1899 until independence in 1956. For most of that time, the British policy was to divide the country into two essentially separate regions – the Islamic, Arabized north and the increasingly Christian African south. The Sudanese journalist Zeinab Badawi’s grandfather fought on the Sudanese side at Omdurman, and her father was a leading figure in the modern politics of this divided country:

It’s an interesting drum because it’s been etched with the Arabic script, because it fell into the hands of the Mahdi, and obviously Arabic is the lingua franca of Sudan and it’s the language spoken by the northern tribes. The drum is very apt, because Sudan is this fusion between Black Africa proper and the Arab world, the real crossroads, like the confluence of the Nile, where the White Nile meets the Blue Nile, in Khartoum. I showed a picture of this drum to my father, and he told me that back in the 1940s and 1950s, when my father was vice-president of the Sudanese Socialist Party and he was in southern Sudan, a fracas broke out between the southern Sudanese and the northerners who were there. At one stage he thinks he saw somebody get a drum, which looked very much like this but obviously newer, and start drumming on it to encourage other southern Sudanese to come to show their strength, to stop this argument getting out of hand between the northerners and the southerners.

Since independence, Sudan has struggled under decades of civil war and sectarian violence, with enormous loss of life. Recently the south has asked for a peaceful separation from the north, and in 2011 there will be a referendum to decide how far such a separation might go. The story of which this slit drum is a part is by no means finished.

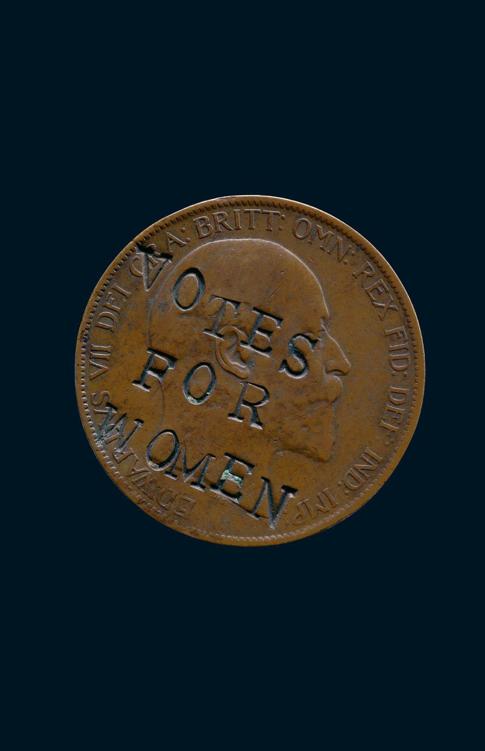

Suffragette-defaced Penny

AD

1903–1918