A History of the World in 100 Objects (79 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

You would have had hundreds of acres being turned over to tea, especially in northern parts of India. They also had success when they took it to places like Ceylon. It would have had an impact on the local population but it did bring jobs to the area, although low-paid jobs – it started off with males being employed, but it was mostly females clipping the tea. Local communities in parts of India and China were benefiting from growing the material and also being able to sell it. But added value from the trade and packaging would have really occurred within the empire and especially within Britain.

Fortunes were made in shipping. The tea trade required huge numbers of fast clipper ships for the long voyage from the Far East, which docked in British harbours alongside vessels bringing sugar from the Caribbean. To get sugar on to a British tea table had until very recently involved at least as much violence as was needed to fill the teapot. The first African slaves in the Americas worked on sugar plantations,

the start of the long and terrible triangular trade that carried European goods to Africa, African slaves to the Americas (as we saw in

Chapter 86

) and slave-produced sugar to Europe. After a long campaign involving many of the people who supported temperance movements, slavery in the British West Indies was abolished in 1833. But in the 1840s there was still a great deal of slave sugar around – Cuba was a massive producer – and it was of course cheaper than the sugar produced on free plantations. The ethics of sugar were complex and intensely political.

The most peaceful part of the tea set is, not surprisingly, the milk jug, though it too is part of a huge social and economic transformation. Until the 1830s, for urban dwellers to have milk, cows had to live in the city – an aspect of nineteenth-century life we’re now barely aware of. Suburban railways changed all that. Thanks to them, the cows could leave town, as an 1853 article in the

Journal of the Royal Agricultural Society of England

makes clear:

A new trade has been opened in Surrey since the completion of the South-Western Railway. Several dairies of 20 to 30 cows are kept and the milk is sent to the various stations of the South-Western Railway, and conveyed to the Waterloo terminus for the supply of the London Market.

So our tea set is really a three-piece social history of nineteenth-century Britain. It is also a lens through which historians such as Linda Colley can look at a large part of the history of the world:

It does underline how much empire, consciously or not, eventually impacts on everybody in this country. If in the nineteenth century you are sitting at a mahogany table drinking tea with sugar, you are linked to virtually every continent on the globe. You are linked with the Royal Navy, which is guarding the sea routes between these continents, you are linked with this great tentacular capital machinery through which the British control so many parts of the world and ransack them for commodities, including commodities that can be consumed by the ordinary civilian at home.

The next object comes from another tea-drinking island nation, Japan. But, unlike Britain, Japan had done all it could to keep the rest of the world at bay and joined the global economy only when forced to do so by the United States – literally at gunpoint.

Hokusai’s

The Great Wave

AD

1830–1833

In the early nineteenth century Japan had been effectively closed off from the world for 200 years. It had simply opted out of the community of nations.

Kings are burning somewhere,

Wheels are turning somewhere,

Trains are being run,

Wars are being won,

Things are being done

Somewhere out there, not here.

Here we paint screens.

Yes … the arrangement of the screens.

This is Stephen Sondheim’s musical tableau of the secluded and calmly self-contained country in 1853, just before American gunships forced its harbours to open to the world. It is a witty caricature of the dreamy and aesthetic Japanese, serenely painting screens while across the seas Europe and America industrialize and political turmoil rages.

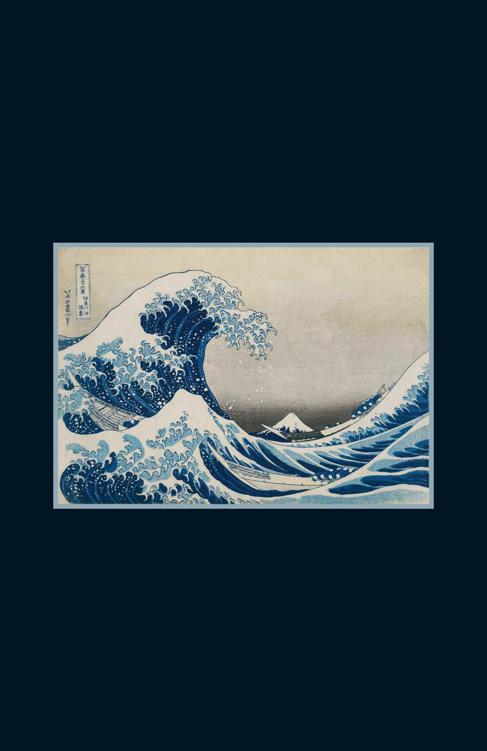

This is an image the Japanese themselves have sometimes wanted to project, and it is how the most famous of all Japanese images,

The Great Wave

, is sometimes read. This bestselling woodblock print, made around 1830 by the great artist Hokusai, is one of his series of thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. The Museum has three impressions of

The Great Wave.

The one shown here is an early one, taken when the woodblock was still crisp, which means it has sharp lines and clear, well-integrated colours. At first sight it presents a beautiful picture of a deep blue wave curling above the sea with, far in the distance, the tranquil, snow-capped peak of Mount Fuji. It is, you might think, a stylized, decorative image of a timeless Japan. But there are other ways of reading Hokusai’s

Great Wave

. Look a little closer and you see that the beautiful wave is about to engulf three boats with frightened fishermen, and Mount Fuji is so small that you, the spectator, share the feeling that the sailors in the boats must have as they look to shore – it’s unreachable, and you are lost. This is, I think, an image of instability and uncertainty.

The Great Wave

tells us about Japan’s state of mind as it stood on the threshold of the modern world, which the US was soon going to force it to join.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, as the Industrial Revolution began, the great manufacturing powers, above all Britain and the United States, were aggressively looking for new sources of raw materials and new markets for their products. The world, these free-traders believed, was their oyster, and it was one they intended to force open. To them, it seemed incomprehensible – indeed intolerable – that Japan should refuse to play its full part in the global economy. Japan, on the other hand, saw no need to trade with these pushy would-be partners. Its existing arrangements suited it very well.

The country had closed almost all its ports at the end of the 1630s, expelling traders, missionaries and foreigners. Japanese citizens were not permitted to leave the country, nor could foreigners enter – disobedience was punished by death. Exceptions were made only for Dutch and Chinese merchants, whose shipping and trade were restricted to the port city of Nagasaki. There goods were regularly imported and exported (as we saw in

Chapter 79

, the Japanese were quick to jump into the gap in the European porcelain market left by political problems in China in the mid seventeenth century) but on terms of trade laid down solely by the Japanese. In dealing with the rest of the world, they called the shots. This was not so much splendid isolation as selective engagement.

If foreign people could not enter Japan, foreign things most certainly could. We can see this very clearly if we look closely at the composition, physical and pictorial, of

The Great Wave.

We see a rather traditional-looking Japanese scene – the enormous wave curling over the long, open fishing boats, dwarfing them and dwarfing even Mount Fuji in the distance. It is printed on traditional Japanese mulberry paper, just under the size of a sheet of A3, in subtle shades of yellow, grey and pink, but it is the deep, rich blue that dominates – and startles. For this is not a Japanese blue – it is Prussian blue or Berlin blue, a synthetic dye invented in Germany in the early eighteenth century and much less prone to fading than traditional blues. Prussian blue was imported either directly by Dutch traders or, more probably, via China, where it was being manufactured from the 1820s. The blueness of the

Great Wave

shows us Japan taking from Europe what it wants to take, and with absolute confidence. The Views of Mount Fuji series was promoted to the public partly on the basis of the exotic, beautiful blue used in its printing – prized because of its very foreignness. Hokusai has taken more than colour from the West – he has also borrowed the conventions of European perspective to push Mount Fuji far into the distance. It is clear that Hokusai must have studied European prints, which the Dutch had imported into Japan and which circulated among artists and collectors. So

The Great Wave,

far from being the quintessence of Japan, is a hybrid work, a fusion of European materials and conventions with a Japanese sensibility. No wonder this image has been so loved in Europe: it is an exotic relative, not a complete stranger.

It also, I think, shows a peculiarly Japanese ambivalence. As a viewer, you have no place to stand, no footing. You too must be in a boat, under the Great Wave, and in danger. The dangerous sea over which European things and ideas travelled has, however, been drawn with a profound ambiguity. Christine Guth has studied Hokusai’s work, especially

The Great Wave

, in depth:

It was produced at a time when the Japanese were beginning to become concerned about foreign incursions into the islands. So this great wave seemed, on the one hand, to be a symbolic barrier for the protection of Japan, but at the same time it had also suggested the potential for the Japanese to travel abroad, for ideas to move, for things to move back and forth. So I think it was closely tied to the beginnings of the opening of Japan.

In the long years of relative seclusion Japan, governed by a military oligarchy, had enjoyed peace and stability. There were strict codes of public behaviour for all classes, with laws on private conduct,

marriage, weapons and much else for the ruling elite. In this highly controlled atmosphere, the arts had flourished. But all this depended on the rest of the world staying away, and by the 1850s there were many outsiders who wanted to share in the profits and privileges enjoyed by the Chinese and the Dutch, and to trade with this prosperous and populous country. Japan’s rulers were reluctant to change, and the Americans came to the conclusion that free trade would have to be imposed by force. The story told in Stephen Sondheim’s ironically titled

Pacific Overtures

actually happened in 1853, when Japan’s self-imposed isolation was breached by the very real Commodore Matthew Perry of the US Navy, who sailed into Tokyo Bay uninvited and demanded that the Japanese begin to trade with the US. Here’s a snatch of the letter from the president of the United States that Perry delivered to the Japanese emperor:

Many of the large ships-of-war destined to visit Japan have not yet arrived in these seas, and the undersigned, as an evidence of his friendly intentions, has brought but four of the smaller ones, designing, should it become necessary, to return to Edo in the ensuing spring with a much larger force.

But it is expected that the government of your imperial majesty will render such return unnecessary, by acceding at once to the very reasonable and pacific overtures contained in the president’s letter …

This was textbook gunboat diplomacy, and it worked. Japanese resistance melted, and very quickly the Japanese embraced the new economic model, becoming energetic players in the international markets they had been forced to join. They began to think differently about the sea that surrounded them, and their awareness of the possible opportunities in the world beyond grew fast.

The Japanologist Donald Keene, from Columbia University, sees the wave as a metaphor for the changes in Japanese society:

The Japanese have a word for insular which is literally the mental state of the people living on islands:

shimaguni konjo

.

Shimaguni

is ‘island nations’

konjo

is ‘character’

.

The idea is they are surrounded by water and, unlike the British Isles, which were in sight of the continent, are far away. The uniqueness of Japan is often brought up as a great virtue. A new change of interest in the world, breaking down the classical barriers, begins to emerge. I think the interest in waves suggests the allure of going elsewhere, the possibility of finding new treasures outside Japan, and some Japanese at this time secretly wrote accounts of why Japan should have colonies in different parts of the world in order to augment their own riches.