A History of the World in 100 Objects (82 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Those are the words of ‘The Internationale

’

, the great socialist hymn written in France in 1871. In Russia in the 1920s, it was adopted by the Bolsheviks as the anthem of the Russian Revolution. The original words were about looking forward to a time of future revolution, but significantly the Bolsheviks changed the tense in the Russian translation, moving it from the future to the present – the Revolution was now. The workers, at least in theory, had taken control.

Throughout this book we have seen images of individual rulers – from Ramesses II and Alexander the Great, to the Oba of Benin and King Edward VII – but here we have the image of a new kind of ruler, not an ‘I’ but a ‘We’, not an individual but a whole class, for in Soviet Russia we see the power of the people, or, rather, the dictatorship of the proletariat. The object in this chapter is a painted porcelain plate that celebrates the Russian Revolution and the new ruling class. In vivid orange, red, black and white, it shows a revolutionary factory glowing with energy and productivity, and, in the foreground, a symbolic member of the proletariat striding into the future. Seven decades of communism are about to begin.

The twentieth century was dominated by ideologies and war: two world wars; fights for independence from colonial powers, and post-colonial civil wars; fascism in Europe, military dictatorships across the world; and revolution in Russia. The great political contest, lasting for most of the century, was between liberal democracy on the one hand, and central state direction on the other. By 1921, the year in which the plate was painted, the Bolsheviks had imposed on Russia a new political system based on Marxist theories of class and economics, and were setting about building a new world. It was a Herculean task – the country had been abjectly defeated in the First World War and the new regime was under threat from foreign invasion and civil war. The Bolsheviks needed to motivate and lead the Soviet workers with whatever means they had at their disposal. One of those means was art.

The designer has exploited the circular shape of the plate to intensify the image’s symbolic power. At the centre, in the distance, is a factory painted in red – this is clearly a factory that belongs to the workers – puffing white smoke, evidence of healthy productivity, with a radiant sunburst of vivid yellow and orange driving away the dark forces of the repressive past. On a hill in the foreground, a man strides in from the left of the picture. He’s aglow, like the factory, with a golden aura around him, painted in red silhouette without any detail, but we know he is young and that he is looking fervently ahead. He clearly represents not an individual but the entire proletariat, moving into the brighter future that they are going to create. At his foot is an industrial cogwheel and in his hand the hammer of the industrial workers. With his next stride he will trample over a barren piece of ground where the word

KAPITAL

lies broken, its letters scattered over the rocks. The plate had been made twenty years earlier, in 1901, and left blank. The artist who designed it, Mikhail Mikhailovich Adamovich, transformed a piece of imperial porcelain into lucid and effective Soviet propaganda. It is this re-purposing that fascinates the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm:

The most interesting thing about this is precisely that in one object you can see the old regime and the new regime, and the change from the one to the other. There are very few objects like this where historic change is so clearly present before you. Ideology is important as far as the artists were concerned. There was this enormous sense, among the people who

felt themselves to have made the revolution, that we have done something that nobody in the world has done. We are creating a completely new world, which won’t be complete until both Russia and the world are transformed, and we have the duty of showing it and pushing it forward – that’s the ideology.

Not long after the Bolshevik takeover, the Imperial Porcelain Factory was nationalized, renamed the State Porcelain Factory and placed under the authority of an official with the ringing utopian title of ‘The People’s Commissar of Enlightenment’. As the Commissar of the State Porcelain Factory wrote to the Commissar of Enlightenment:

The Porcelain and Glass Factories … cannot be just factory and industrial enterprises. They must be scientific and artistic centres. Their aim is to encourage the development of Russia’s ceramic and glass industry, to seek and develop new paths in production … to study and develop artistic form.

In the Russia of 1921, the year of our plate, there was an acute need for striking messages of unity and hope. The country was embroiled in civil war, deprivation, drought and famine: over four million Russians starved to death. The worker-owned factories like the one shown on our plate were producing a fraction of what they had done before the Revolution. Eric Hobsbawm sees the art typified by the plate as indicating the power of hope in a seemingly hopeless situation:

It was made at a time when almost all the people engaged in it were hungry. There was famine in the Volga and people died of hunger and typhus. It was a time when you would say, ‘This is a country lying flat on its back, how can it recover?’ And what I think one has to re-create by imagination is the sheer impetus of people doing it, saying: in spite of everything we are still building this future, and we are looking forward to the future with enormous confidence.

The plate brings us what one of the ceramic artists called ‘news from a radiant future’. Normally regimes will revisit and reorder the past, appropriating it to their current needs, as we have seen many times, but the Bolsheviks wanted people to believe that the past was over and that the new world was going to be built from scratch.

This image of the new egalitarian world of the proletariat is painted on porcelain – the luxury material historically associated with aristocratic culture and privilege. Painted by hand over the glaze, it was for display, not for use. The plate is scallop-edged and very fine – it was in fact a blank made before the Revolution that had been left over from the Porcelain Factory’s imperial days. The Empress Elizabeth had set up the Imperial Porcelain Factory near St Petersburg in the eighteenth century, to produce porcelain which would rival the best that Europe could offer, for use at court and for official imperial gifts, as Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of Russia’s State Hermitage Museum, explains:

Russian porcelain became an important part of Russian cultural production. Russian Imperial Porcelain became famous: beautiful dishes that are now extremely expensive at world auctions. It is a good example of art in connection with economy and politics, because it was always a kind of expression of Russian empire – military pictures, military parades, the love of life of ordinary people, pictures from the Hermitage – everything which Russia wanted to present to the world and to itself in a beautiful manner.

This plate is an example in microcosm of the way in which the Soviet rhetoric of total rupture could never match the reality: given the speed of the Revolution, the Bolsheviks had to take over existing structures where they could, so much of Soviet Russia continued to echo Tsarist patterns. They had to do it that way – but in this case, they deliberately

chose

to do it. On the back of the plate are two factory marks. Underneath the glaze, applied when the blank plate was first made, is the Imperial Porcelain Factory mark of Tsar Nicholas II for the year 1901. Over the glaze is painted the hammer and sickle of the Soviet State Porcelain Factory and the date 1921. This painted plate was made in two stages, twenty years apart, and in astonishingly different political circumstances.

You would have expected the Tsar’s monogram to have been painted over, blotting out the imperial connection, and it often was. But, as somebody at the factory realized, there was a great advantage in leaving both marks visible. It made what was already a collector’s item even more desirable, so it could be sold abroad for a much higher price. The regime was desperate to raise foreign currency, and the sale of artistic and historic objects like this plate was one obvious part of the solution. The records of the new State Porcelain Factory report that, ‘For foreign markets the presence of these marks alongside the Soviet marks is of great interest, and prices for the objects abroad shall doubtless be set higher if the earlier marks are not painted over.’

The imperial factory mark of Tsar Nicholas II and the hammer and sickle of the Soviet state

So we have the surprising situation of a socialist revolutionary regime making luxury goods to sell to the capitalist world. And you could argue this was perfectly coherent: profits from the plate supported Soviet international action, designed to undermine the very capitalists they were selling to, while at the same time the porcelain propaganda promulgated the Soviet message to Russian enemies.

‘

Artistic industry,’ wrote the critic Yakov Tugenkhold in 1923, ‘is that happy battering ram which has already broken down the wall of international isolation.’

This conflicted, symbiotic relationship between the Soviet and the capitalist worlds – initially seen as a transitional necessity until the West was won for workers and communism – became the norm for the rest of the century. The front of the plate shows us the compelling clarity of the early Bolshevik dream. The back shows us pragmatic compromise – negotiation with the imperial past and political realities, and a complex economic modus vivendi with the capitalist world. Broadly, this is the pattern that would be sustained for the next seventy years as the world settled into two huge, competing but in many ways interdependent ideological blocs. The front and back of this plate chart the path from worldwide revolution to the stability of the Cold War.

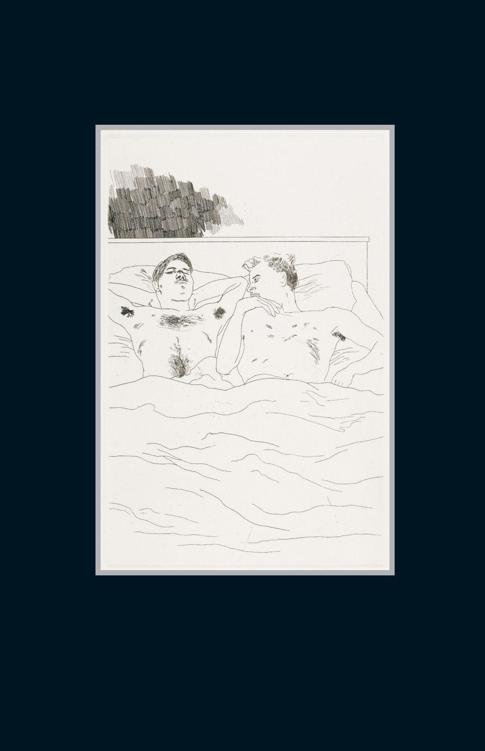

Hockney’s

In the Dull Village

AD

1966

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban

And The Beatles’ first LP.

So wrote the poet Philip Larkin, master of the regretful lyric, in one of his jollier verses, pinpointing what were for him the key aspects of the Swinging Sixties – sex, music and then more sex. All generations think they have invented sex, but none thought they had done it as thoroughly as the young people of the 1960s. Of course there was a great deal more to the sixties than that, but the decade has now taken on mythic status as a time of transforming freedom – or destructive self-indulgence – and the myths are not unjustified. All over the world established structures of authority and society were challenged, and in some cases brought down, by spontaneous mass activism in pursuit of political, social and sexual freedoms.

In the previous two chapters we examined big political issues – the realization of rights for whole sections of society, whether votes for women or power (in theory) for the proletariat. In the 1960s the campaigns were more about ensuring that every individual citizen could exercise those rights, asserting that everybody should be free to play their full part in society and to live the way they wished, as long as they caused no harm. Some of these new freedoms were hard won, and people paid with their lives: this was the decade of Martin Luther King and black civil rights in the United States; of the Prague Spring, the heroic Czech rebellion against Soviet Communism; of the 1968 Paris student uprisings and waves of campus discontent across Europe and America; of the campaigns oppposing war in Vietnam and supporting Nuclear Disarmament.