A History of the World in 100 Objects (71 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Historically, performances in the Theatre of Shadows lasted throughout the night. Light from an oil lamp behind the puppeteer’s head cast the shadows from the puppets on to a white sheet. Some members of the audience – usually the women and children – sat on the shadow side of the screen, while the men would sit on the favoured other side. The puppeteer, known as a

dalang

, would not only control the puppets but also conduct the accompanying music performed by a Gamelan orchestra.

Sumarsam, a leading

dalang

in the Theatre of Shadows today, gives us an idea of how complicated it is to pull off a smooth shadow-puppet performance:

You need to control the puppets themselves, sometimes two, three or sometimes up to six puppets at one time, and the puppet master will have to know when to give a signal to the musicians to play. And of course the puppet master also gives voices to the puppets in different dialogues, and sometimes also he sings mood songs to set up the atmosphere of different scenes. He will have to use his arms and legs – all of this to be done while he is sitting down cross-legged. It’s fun to do it, but also a fairly challenging task. The stories can be updated, but the structure of the plot is always the same.

The stories told in the Theatre of Shadows are drawn largely from two great Hindu Indian epics – the Mahabharata and the Ramayana,

both written well over 2,000 years ago. They have always been widely known in Java, for Hinduism, with Buddhism, had been the main religion there before Islam became the dominant faith.

Like the Buddhism that inspired Borobudur around 800 (see

Chapter 59

) and the Hinduism that created the Mahabharata, Islam came to Java through the maritime trading routes that linked Indonesia to India and the Middle East. Local Javanese rulers quickly saw advantages in becoming Muslim: besides any spiritual attraction, it facilitated both their trade with the existing Muslim world and their diplomatic relations with the great Islamic powers of Ottoman Turkey and Mughal India. The new religion brought major changes in many aspects of life, but on the whole local Javanese culture and belief absorbed Islam, rather than being totally replaced by it.

The newly Islamic rulers seem to have gone along with this – they actively patronized the Theatre of Shadows and its Hindu stories, which remained as popular as ever. The audience, then as now, would immediately recognize the Bima puppet. In the Mahabharata, Bima is one of five heroic brothers (you can follow their exploits today in animations on the internet) and the great warrior among them – noble, plain-speaking and superhumanly strong, equal to 10,000 elephants, but also with a very good line in banter and something of a celebrity cook. One touch of his claw-like nails means death to his enemies.

The Bima puppet’s black face expresses inner calm and serenity, unlike depictions of the ‘bad guys’ in the Theatre of Shadows, who are often coloured red for vindictiveness and cruelty. But his shape also tells us that an Islamic influence has found its way into this traditional Hindu art. This becomes obvious if we compare our Javanese puppet of Bima, with its caricature nose and claw hands, and another puppet of Bima made on the nearby island of Bali, which remained Hindu. The figure from Bali has rounded, more natural facial features, and his arms and legs are in more normal proportions to his body. Many in Java today would argue that these differences are explained by religion; and that the traditional Hindu puppets were deliberately reshaped by their Javanese Muslim makers in order to avoid the Islamic prohibition on creating images of humans and gods. Stories are told of attempts in the sixteenth or seventeenth century to ban the Theatre of Shadows; others tell of Sunan Giri, a noted Muslim saint, who ingeniously came up with the idea of distorting the features of the puppets in order to get around the prohibition – a happy compromise that may explain our Bima’s odd appearance.

A puppet of Bima from Bali shows more naturalistic features

Today Indonesia, with 245 million inhabitants, is the world’s most populous Islamic nation, and the Theatre of Shadows is still very much alive. The Malaysian-born author Tash Aw describes the continuing role of shadow theatre:

Even today there is a great consciousness of what goes on in the realms of shadow theatre. It’s an art form that is constantly being refreshed, that’s constantly being put to new and very exciting use. And, although the body of the works are drawn largely still from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, younger puppeteers are constantly using the shadow theatre to inject life and humour and a sort of bawdy commentary on Indonesian politics, which is difficult to replicate elsewhere. Just after the financial crisis in 1997, I remember a virtuoso monologue in Jakarta which roughly translates as ‘The tongue is still comatose’ or ‘The tongue is still mute’, in which the current President Habibie was cast as a ridiculous character called Gareng, who is short with beady eyes, incredibly earnest, but very inefficient. So, in many ways shadow theatre has become a source of social and political satire in a way that is difficult for TV, radio and newspapers to do, because those are much more easily censored; the shadow theatre is much more malleable, much more in touch with the grass roots and therefore much more difficult to control.

But it’s not just the opposition who make use of the Theatre of Shadows. The former president Sukarno, the first president after Indonesia gained independence from the Dutch following the Second World War, liked to identify himself with shadow-puppet characters, and especially with Bima – a righteous, mighty fighter, speaking like the common man rather than in elite language. Sukarno was often referred to as the

dalang

, the puppet master, of the Indonesian people – the one to give them voice and direct them in their new state, leading them in their national epic, as indeed he did for twenty years before being ousted in 1967.

But why is

this

Bima now in the British Museum? The answer, as so often, lies in European politics. For five years between 1811 and 1816, as part of the worldwide struggle against Napoleonic France, Britain occupied Java. The new British governor, Thomas Stamford Raffles, who would later found Singapore (see

Chapter 59

), was a serious scholar and a great admirer of Javanese culture of every period and, like all rulers of Java, he patronized the Theatre of Shadows and collected puppets. Our Bima comes from him. That short period of British rule explains something else – why the car from which the young Barack Obama saw a Hindu god in the streets of Muslim Jakarta was driving on the left-hand side of the road.

Mexican Codex Map

AD

1550–1600

The Shi’a ‘alam, Mughal miniature and Javanese shadow puppet represent cultures in which different faiths have managed to find reasonably positive ways of living together – in India, Iran and Indonesia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries religious tolerance was a hallmark of effective statecraft. But in Mexico around that time Christianity came as an instrument of conquest and was only slowly absorbed by the indigenous population. Now, 500 years later, more than 80 per cent of the population of Mexico is Catholic. In the process the physical landscape changed too: the invaders crushed temples and raised churches all over the Aztec Empire. It looks today like the most brutal and most complete replacement imaginable of one culture by another.

In the Zócalo, the main square of Mexico City, the palace of the Spanish viceroy stands on the very site of the demolished palace of Moctezuma. Nearby are the ruins of what was once the Aztec temple, whose sacred precinct is now largely taken up by the huge Spanish Baroque cathedral dedicated to the Virgin Mary. From the Zócalo, it looks as if the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521 was in every way cataclysmic for indigenous traditions, and that is how the story has generally been told. The reality, however, was more gradual and perhaps more interesting. The local people kept their own languages – and, for the most part, their own land, although the fatal diseases which the Spanish had unwittingly brought with them meant that much land was freed up for the new settlers from Spain. The object in this chapter shows us something of how the complex amalgamation of faiths took place, and in it we can see both Spanish imperial methods and the resilience of local traditions.

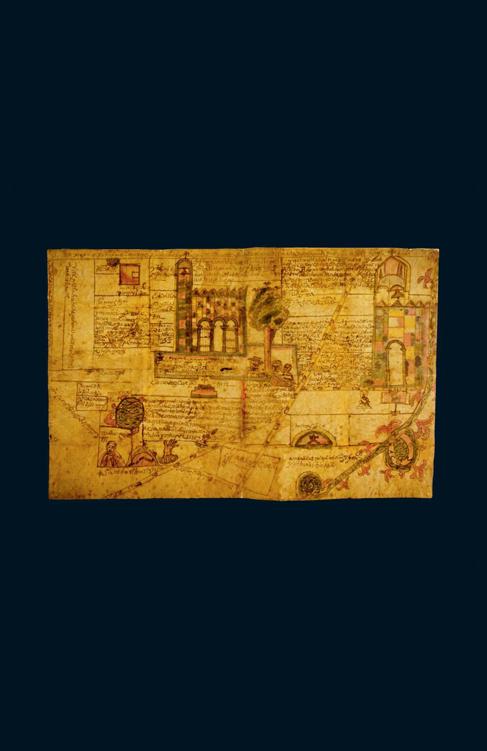

It is an annotated map about 75 centimetres (30 inches) wide and 50 centimetres (20 inches) tall, painted on very rough paper, in fact Mexican bark that has been beaten into a sheet. On the map are geometrically drawn lines indicating, presumably, divisions of fields, with names written into them to show the owners, a small blue river with wavy lines, and a forking road, with feet on it showing that it is a thoroughfare. Then on top of this diagram are painted images – in the middle a tree, and under it three figures wearing European dress, and then two large churches with bell towers, painted in bright colours of blue, pink and yellow, the principal features of the map. One of them is named Santa Barbara, the other Santa Ana.

The map represents an area in the province of Tlaxcala, to the east of Mexico City, a region whose people had bitterly resented Aztec rule and who had enthusiastically joined the Spaniards in defeating them (see

Chapter 78

). This may explain why so many of the names of land holders on the map show marriages between Spanish settlers and native Indian aristocrats, evidence of a remarkable fusion between the two peoples and the emergence of a new, mixed, ruling class. More surprisingly, a similar fusion took place in the church. For example, many communities in the Tlaxcala area had been protected by the indigenous Toci, grandmother of the Mexican gods, who after the conquest was replaced as local patroness by St Anne (Santa Ana), in Catholic tradition the grandmother of Christ. The grandmother may have changed her name, but it is unlikely that for the local worshippers she had in any serious way changed her nature.

Apart from disease, religion was the most significant new aspect of Mexican life under the Spanish. Catholic missionaries came with the conquerors in the 1520s and transformed the spiritual landscape. While in many places the conquest was violent, the conversion of local people to Catholicism was not usually forced: the missionaries were genuinely intent on instilling the true faith, so regarded compulsory conversion as worthless. Even if many Indians willingly converted, it is hard to believe they would have welcomed the destruction of their previous places of worship, yet this was a key part of Spanish policy. A Franciscan friar writing ten years after the conquest boasts of the achievements of this new, Mexican, church triumphant:

More than 250,000 men have been baptized, 500 temples have been destroyed and more than 26,000 figures of demons, which the Indians worshipped, have been demolished and burned.

The churches of Santa Barbara and Santa Ana dominate the landscape on our map; one has clearly been built on top of a destroyed native temple. The art historian Samuel Edgerton describes the technique:

Many of these Mexican churches are built on the platforms of old pagan temples. It’s a very clever ruse to help the Indians feel comfortable in the new churches, which were literally on top of the old church or temples. The central church has in front of it a large courtyard, what is today called an

atrio

or a

patio

. This was an innovation that the friars introduced to the buildings of these churches in Mexico because in the beginning the churches were often small, and you could not crowd in all the Indians who were being brought in here to be converted. So you had them stand in this large courtyard, and there they were preached to from an open chapel – it was easier for the church then to work as a ‘theatre for conversion’.