A History of the World in 100 Objects (72 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

The churches on our map – these theatres of conversion – were built within an existing landscape of roads, watercourses and houses. Names and places are given in a mixture of Spanish and the local Nahuatl language: for example, the church of Santa Barbara is in a village called Santa Barbara Tamasolco.

Tamasolco

means place of the toad, which almost certainly had a pre-Christian religious significance, now lost. The artist has painted a toad on the map, and the two religious traditions live on in the eccentric place-name ‘Santa Barbara at the Place of the Toad’.

They also clearly lived on in the minds of the converted. An inscription on the map tells us: ‘Juan Bernabe said to his wife: “Sister of mine, let us give soul to our offspring, let us plant the willows that shall be our memory.” ’ In this lyrical glimpse of private faith, Juan Bernabe, despite bearing two Christian saints’ names, obviously still believes that his children’s salvation will be achieved in communion with the natural world of native tradition, rather than, or at least as well as, inside the Catholic church down the road.

The babies of this ‘New Spain’, as the invaders called it, were, like Juan Bernabe, given new Christian names at baptism, but, again like Juan Bernabe, this didn’t necessarily make them good Catholics. Later reformers would crack down on continuing pre-Christian practices and old rituals – incantations, divination and mask-wearing were punished as sorcery or idolatry. But many ceremonies survived through the sheer tenacity of the indigenous people. The most striking modern example is perhaps the way pre-Christian ancestor veneration has merged with the Christian All Souls’ Day to create the Day of the Dead, an entirely Mexican celebration, still vigorously alive, in which on 2 November every year the living remember their dead, with skulls and skeletons in colourful costumes, festive music, special offerings and food – a celebration that owes as much or more to native Indian religious practices as to Catholic piety.

The Nahuatl language that appears on our map has just about survived. A census carried out in 2000 revealed that only 1.49 per cent of the population could still speak it. Recently, however, the mayor of Mexico City has said he wants all city employees to learn Nahuatl, in an effort to revive the ancient tongue. Quite a few Nahuatl words do in fact survive today – although probably few of us realize we are using Nahuatl when we talk about tomato, chocolate or avocado. Significantly, but not surprisingly, no religious Nahuatl words have stayed with us – the missionaries’ teaching saw to that.

Five centuries after the conquest, the Mexican people today are increasingly eager to revive their pre-Hispanic past as a defining element of their national identity. But in the realm of faith, the legacy of the Christian conversion is still overwhelming. In spite of the great communist anti-clerical revolutions of the twentieth century, as the Mexican-born historian Dr Fernando Cervantes emphasizes, Mexico remains inextricably linked to the Catholic faith:

There is a very strong anti-religious, anti-clerical nationalist ideology in Mexico, but it’s very ambivalent because even the most atheistic Mexicans will never deny that they are devoted to the Virgin of Guadalupe, for instance. This is where the Catholic substratum comes through very strongly. You can’t really square the circle of being Mexican and not being in some senses Catholic. So I think that this is where you can see how strong the early evangelization was and how alive it still is.

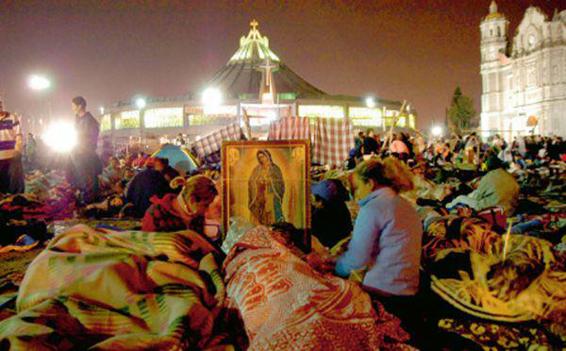

Crowds flood to the shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe

Everything that Dr Cervantes is talking about, indeed everything that our little map reveals about the Christianization of Mexico, is summed up on a colossal scale at the shrine of Guadalupe in the suburbs of Mexico City. After the Vatican, it is now the most visited Catholic shrine in the world. It was there, on the site of an Aztec shrine, that in December 1531, just ten years after the conquest, the Virgin Mary appeared to a young Aztec man whom the Spaniards called Juan Diego. She asked him to trust in her and she miraculously imprinted her image on his cloak. A church was built on the site of Juan Diego’s vision, the image on the cloak produced miracles, and conversions followed in huge numbers. The crowds flooded into Guadalupe. For a long time the Catholic clergy were worried that this was in fact the worship of an Aztec goddess being continued where there had once been an Aztec shrine; but the combined forces of the two religious traditions have over the centuries proved irresistible. There are now so many visitors to Guadalupe that you have to move in front of the miraculous image on a conveyer belt. In 1737 the Virgin of Guadalupe was declared patroness of Mexico, and in 2002 Pope John-Paul II declared Juan Diego, the young Aztec born under Moctezuma, a saint of the universal Catholic Church.

Reformation Centenary Broadsheet

AD

1617

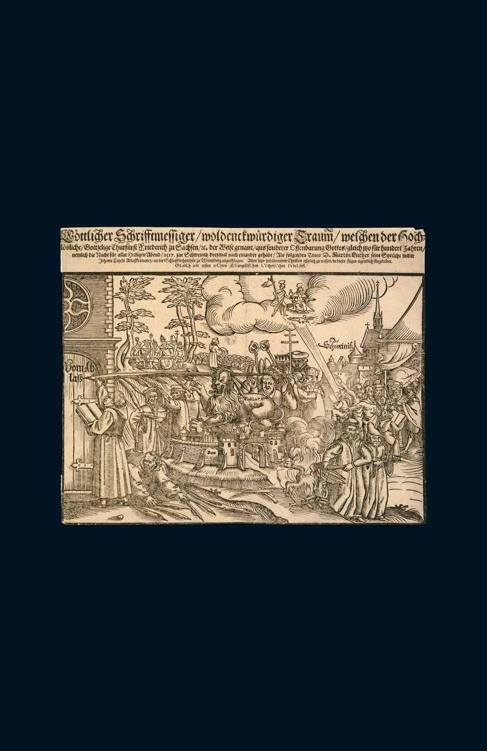

You can hardly turn on the radio or open a newspaper these days without being bombarded by yet another anniversary – a hundred years since this, two hundred years since that. Our popular history seems to be written increasingly in centenaries, all generating books and exhibitions, T-shirts and special souvenir issues, in a frenzy of commemoration. Where did this habit of anniversary festivities begin? The answer takes us to the great struggle for religious freedoms played out across northern Europe in the seventeenth century. The first of all these modern centenary celebrations seems to have been organized in Germany, in Saxony in 1617; the event it was commemorating had taken place a hundred years earlier. In 1517, the story goes, Martin Luther picked up a hammer and nailed what was effectively his religious manifesto – his ninety-five theses – to a church door; in doing so he triggered the religious turmoil that would become the Protestant Reformation. The object in this chapter is a souvenir poster showing Luther’s famous act, on a large single sheet of paper called a broadsheet, made for the centenary. And it isn’t just a celebration, it’s about getting ready for war.

In 1617, when this broadsheet was made, European Protestants were facing an uncertain and dangerous future. The New Year had opened with public prayers by the Pope in Rome calling for the reunion of Christendom and the eradication of heresy. He was effectively calling the Catholic Church to arms against the Reformation. It was clear to many that a terrible religious war was about to break out. In response the Protestants tried to find a way of rallying their supporters for the fight, but unlike the Catholic Church they had no central authority to issue directions to the faithful. Protestants had to find other ways of insisting that the Reformation had been part of God’s plan for the world, that individuals had no need of priests to gain access to God’s mercy, that the Roman church was corrupt, and that Luther’s Reformation was essential to the salvation of every living soul. Above all, they needed a view of their past that would give all Protestants strength to face the terrifying future.

Before this point, no particular day or moment had been identified as the beginning of the Reformation. But leading Protestants in Saxony realized that it was now a hundred years since the heroic moment when, on 31 October 1517, Luther had first publicly challenged the authority of the Pope, so it was said, by nailing his ninety-five theses on to the door of the Castle Church at Wittenberg in Saxony. So, with a masterly sense of media management, they launched the first centenary celebration in the modern sense. All the familiar razzmatazz was there: ceremonies and processions, souvenirs, medals, paintings, printed sermons, and the broadsheet – a woodblock print which illustrates the critical day that Protestants now saw as the beginning of the first step on their radical religious journey.

The broadsheet is a crowded composition, but the message is quite clear: in a dream, God is revealing to the elector of Saxony the historic role of Martin Luther. We see the elector asleep. Below him, Luther reads the Bible in a great shaft of light coming down from heaven, where the Trinity is blessing him. As Luther looks up, light pours down on to the page in front of him: here, scripture is the word of God, and to read the scripture is to encounter God – and this is not happening inside a church. You could not have a simpler statement that for Protestants, Bible-reading is the foundation of faith, a foundation which, thanks to the new technology of printing, was now available to all believers in their own homes.

This broadsheet was produced in Leipzig, which in 1617 was a centre of the European printing trade. As the religious historian Karen Armstrong describes, by then the whole pattern of religion in northern Europe had been changed by this new emphasis on reading the word of God:

It is very noticeable in this picture, the emphasis on the written word. Up until this point religion had been precisely about listening for what lay beyond language. People had thought not so much in terms of words or concepts or arguments but in terms of images, of icons, in terms of music, of action. Now, because of the invention of printing, which helped Luther disseminate his ideas, everything is going to become much more wordy. That has been rather the plague of Western religion ever since, because we are endlessly now stuck in words. Printing enabled people for the first time to own their own Bibles, and this meant that they read them in an entirely different way.

Without printing, the Reformation might well not have survived, and the broadsheet’s combination of text and illustration shows that along with words the image was still very much alive. Seventeenth-century Europe was still largely illiterate – even in the cities no more than a third of people could read – so prints with images and just a few key words were the most effective means of mass communication. Even today we all know a well-crafted cartoon can be lethal in public debate.

The front of the print shows Luther writing on the church door, with the world’s biggest quill pen, the words

Vom Ablass

– ‘About Indulgence’ – the title of his virulent attack on the Catholic sale of indulgences, the system by which souls spent less time in purgatory in return for cash paid to the church during their lifetime. The selling of indulgences had fuelled anti-papal feeling in Germany. Luther’s quill stretches half way across the print – to a walled city, helpfully labelled Rome, and straight through the head of a lion labelled Pope Leo X, who squats on top of it. As if that wasn’t enough, the quill then knocks the papal crown off the head of the Pope shown in human form. Never was a pen mightier than this one. The message is coarse but clear – Luther, inspired by reading the scriptures, has destroyed papal authority by the power of his pen.

Woodblocks like this were the first mass medium – with print runs in the tens of thousands, allowing each single copy to cost just a few pfennigs – the price of a pair of sausages or a couple of pints of ale. Satirical prints were pinned up in inns and market places and then widely discussed. This is in every sense popular art, the equivalent of the tabloid press or a satirical magazine, like

Private Eye.

We asked

Private Eye

’s editor,

Ian Hislop, to comment:

The editor of this broadsheet has done exactly what you’d expect. He’s cracked his hero up, he’s demonized the enemy, turned him into an animal, and then into a ludicrous figure, a sort of blank-looking rather stupid person, who has his hat knocked off. All around the pen there are bits of it fallen off, so that everyone else has got a pen as well – this is about writing, about the word and, even more, about printing, because now the Bible can be printed, and we see that we’re up in heaven here and the word of God comes down from heaven straight on to the page.

So no priests in the way, no Pope, no nothing, to get between you and the word of God. The thing I love about it is that it’s like reading a magazine, there are big pictures with obviously cartoony jokes, and then there are captions everywhere to make sure that you don’t miss anything. My German isn’t really good enough to get a lot of the jokes, but looking at it, I just put my own in. I imagine someone here saying, ‘Abandon Pope all ye who enter here,’ or Luther with the pen is saying ‘It’s the quill of God,’ or a lot of very strict Catholics saying, ‘Yes, but your interpretation is much Luther.’ In fact I hope the jokes are better than that, but it’s pretty clear what’s going on in this picture, and I think it’s terrific.