A History of the World in 100 Objects (66 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

The Europeans are Portuguese, who from the 1470s were sailing down the west coast of Africa in their galleons on their way to the Indies, but who were also seriously interested in West African pepper, ivory and gold. They were the first Europeans to arrive by sea in West Africa, and their large ocean-going ships astonished the local inhabitants. Before then, any trade between West Africa and Europe had been conducted through a series of middlemen, who transported goods over the Sahara by camel. The Portuguese galleons, cutting out all the middlemen and able to carry much bigger cargoes, offered a totally new kind of trading opportunity. They and their Dutch and English competitors, who followed later in the sixteenth century, carried gold and ivory to Europe and in return brought commodities from all over the world that were greatly valued by the Oba’s court, including coral from the Mediterranean, cowry shells from the Indian Ocean to serve as money, cloth from the Far East and, from Europe itself, larger quantities of brass than had ever before reached West Africa. This was the raw material from which the Benin plaques were made.

All European visitors were struck by the Oba’s position as both the spiritual and the secular head of the kingdom, and the Benin brass plaques are principally concerned with praising him. They were nailed to the walls of his palace, rather in the same way that tapestries might be hung in a European court, allowing the visitor to admire both the achievements of the ruler and the wealth of the kingdom. The overall effect was described in detail by an early Dutch visitor:

The king’s court is square … It is divided into many magnificent palaces, houses and apartments of the courtiers, and comprises beautiful and long square galleries, about as large as the Exchange at Amsterdam,

from top to bottom covered with cast copper, on which are engraved the pictures of their war exploits and battles, and are kept very clean

.

Europeans visiting Benin in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries discovered a society every bit as organized and structured as the royal courts of Europe, with an administration able to control all aspects of life, not least foreign trade. The court of Benin was a thoroughly international place, and this is one aspect of the Benin plaques that fascinates the Nigerian-born sculptor Sokari Douglas Camp.

Even when you see contemporary pictures of the Oba, he has more coral rings than anybody else and his chest piece has more coral on it. The remarkable thing about Nigeria is that all the coral and things don’t actually come from our coast, they come from Portugal and places like that. So all of that conversation has always been very important to me – we have things that are supposed to be totally traditional yet they are traditional through trade.

The brass needed to make the plaques was usually transported in the form of large bracelets – called

manillas

– and the quantities involved are staggering. In 1548 just one German merchant house agreed to provide Portugal with 432 tons of brass

manillas

for the West African market. When we look again at the plaque, we can see that one of the Europeans is indeed holding a

manilla

, and this is the key to the whole scene: the Oba is with his officials who manage and control the European trade. The three Africans are in the foreground and are on a far bigger scale than the diminutive Europeans, both of whom are shown with long hair and elaborate feathered hats. The

manilla

shows that the brass brought from Europe is merely the raw material from which Benin craftsmen would create works of art like this; and the plaque itself is a document that makes clear that this whole process is controlled by the Africans. Part of that control was a total prohibition on the export of the brass plaques. So, although carved ivories were exported from Benin in the sixteenth century and were well known in Europe, the Benin plaques were reserved to the Oba himself and were not allowed to leave the country. None had been seen in Europe before 1897.

On 13 January 1897,

The Times

announced news of a ‘Benin Disaster’. A British delegation seeking to enter Benin City during an

important religious ceremony had been attacked and some of its members killed. The details of what actually happened are far from clear and have been vigorously disputed. Whatever the real facts, the British, in ostensible revenge for the killing, organized a punitive expedition which raided Benin City, exiled the Oba and created the protectorate of Southern Nigeria. The booty from the attack on Benin included carved ivory tusks, coral jewellery and hundreds of brass statues and plaques. Many of these objects were auctioned off to cover the costs of the expedition and were bought by museums across the world.

The arrival and the reception of these completely unknown sculptures caused a sensation in Europe. It is not too much to say that they changed European understanding of African history and African culture. One of the first people to encounter the plaques, and to recognize their quality and their significance, was the British Museum curator Charles Hercules Read:

It need scarcely be said that at the first sight of these remarkable works of art we were at once astounded at such an unexpected find, and puzzled to account for so highly developed an art among a race so entirely barbarous …

Many wild theories were put forward. It was thought that the plaques must have come from ancient Egypt, or perhaps that the people of Benin were one of the lost tribes of Israel. Or the sculptures must have derived from European influence (after all, these were the contemporaries of Michelangelo, Donatello and Cellini). But research quickly established that the Benin plaques were entirely West African creations, made without European influence. The Europeans had to revisit, and to overhaul, their assumptions of easy cultural superiority.

It is a bewildering fact that by the end of the nineteenth century the broadly equal and harmonious contacts between Europeans and West Africans established in the sixteenth century had disappeared from European memory almost without leaving any trace. This is probably because the relationship was later dominated by the transatlantic slave trade and, later still, by the European scramble for Africa, in which the punitive expedition of 1897 was merely one bloody incident. That raid and the removal of some of Benin’s great artworks may have spread knowledge and admiration of Benin’s culture to the world, but it has left a wound in the consciousness of many Nigerians – a wound that is still felt keenly today, as Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian writer and Nobel laureate, describes:

When I see a Benin Bronze, I immediately think of the mastery of technology and art – the welding of the two. I think immediately of a cohesive ancient civilization. It increases a sense of self-esteem because it makes you understand that African society actually produced some great civilizations, established some great cultures, and today it contributes to one’s sense of the degradation that has overtaken many African societies, to the extent that we forget that we were once a functioning people before the negative incursion of foreign powers. The looted objects are still today politically loaded. The Benin Bronzes, like other artefacts, are still very much a part of the politics of contemporary Africa and, of course, Nigeria in particular.

The Benin plaques, powerfully charged objects, still move us today as they did when they first arrived in Europe, a hundred years ago. They are arresting works of art, evidence that in the sixteenth century Europe and Africa were able to deal with each other on equal terms, but also contested objects of the colonial narrative.

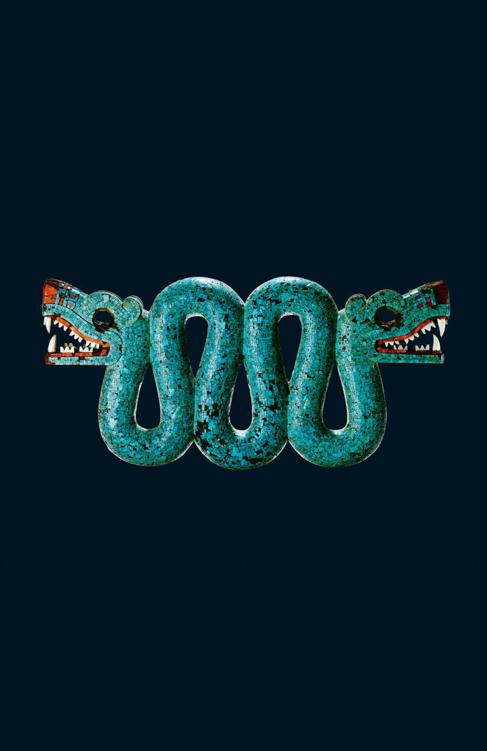

Double-headed Serpent

AD

1400–1600

Any visitor to Mexico City today is likely to hear the sounds of buskers beating Aztec-style drums and wearing feathers and body paint. These buskers are not just trying to entertain passers-by: they are trying to keep alive the memory of the lost Aztec Empire, that powerful, highly structured state that dominated Mexico in the fifteenth century. The buskers would have us believe, and you can believe it if you like, that they are heirs of Moctezuma II, the emperor whose realm was brutally overthrown by the Spaniards in the great conquest of 1521.

In the course of the Spanish conquest much of Aztec culture was destroyed. So how much can we actually know about the Aztecs whom these buskers are honouring? Virtually all the accounts of the Aztec Empire were written by the Spaniards who overthrew it, so they have to be read with considerable scepticism. It is all the more important, then, to be able to examine what we can consider unadulterated Aztec sources, the things made by them that have survived. These things are the documents of this defeated people, and through them we can, I think, hear the vanquished speak.

At the beginning of the sixteenth century the Aztecs, of course, had no idea that they were on the brink of destruction – they were a young and vigorous empire triumphantly in possession of territory and trading networks that ran from Texas in the north to Guatemala in the south and included the great bulk of modern Mexico. They had a flourishing culture that produced elaborate works of art more precious to them than gold – turquoise mosaics.

When some of these mosaics and other Aztec treasures were first brought to Europe by the Spanish in the 1520s they caused an enormous stir – this was the first glimpse of a great civilization in the Americas, completely unknown to Europeans, and evidently every bit as sophisticated and luxurious as their own. This double-headed serpent is one of the most highly crafted and strangely compelling of these rare Aztec survivals.

The serpent is made out of about 2,000 small pieces of turquoise set on to a curved wooden frame, about 40 centimetres (16 inches) wide and half as high. The snake, one body shared by two heads, is in profile; the body curls up and down in a W shape, to finish at each end in a savage, snarling, head. The body of the snake is entirely in turquoise, but a brilliant red shell has been used for the snouts and the gums, and the teeth are picked out in white shell culminating in huge, terrifying fangs. As you move up and down in front of it, and let the light play over the turquoise, the changing colours seem to live, and the pieces look not so much like scales on a snake as feathers shimmering in the sunlight. It is an object which is at once both snake and bird. It is mysterious and disturbing, a work of high artifice and a vehicle of primal power. You know you are in the presence of magic.

The way that the serpent was made gives us a lot of useful information. In the British Museum’s Conservation Department, Rebecca Stacey has been examining the materials that make up the object, as well as the resins or glue that hold the 2,000-odd pieces together.

We have done a range of analyses and looked at the variety of different shells that are present. The bright red shell used on the mouth and around the nose is from the thorny oyster, which was a really highly prized shell in ancient Mexico because of this fabulous scarlet red colour and also because it involved diving to great depths. Even the adhesives, which are plant resins, were important ritual materials because they are the same materials that were used as incense and as ritual offerings – a very important ceremonial life of their own. A number of different plant resins were used: pine resin, fairly familiar, and also tropical bursera resin, which is a much more aromatic resin very much associated with incense and still used in incense in Mexico today.

So the different elements of this magical object are held together – almost literally – by the glue of faith. Rebecca Stacey and scientists across the world have established that turquoise in Aztec Mexico was

transported over huge distances – some pieces were mined more than a thousand miles from the capital Tenochtitlán, now Mexico City. Goods like turquoise and the shells and resin were traded widely across the region, but it is more likely that the components of our serpent were forcibly exacted as tribute – compulsory levies from peoples whom the Aztecs had conquered. This empire had been created in the 1430s, less than a century before the Spaniards arrived, and was maintained by aggressive military power and tribute of gold, slaves and turquoise sent regularly (and reluctantly) to Tenochtitlán from the subject provinces. The wealth generated by this trade and tribute allowed the Aztecs to build roads and causeways, canals and aqueducts, as well as major cities – urban landscapes that astonished the Spaniards as they marched through the empire:

During the morning, we arrived at a broad causeway and continued our march … and when we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land, we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments they tell of in the legends of Amadis, on account of the great towers and buildings rising from the water and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream.