A History of the World in 100 Objects (26 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

Three hounds eye a small duck on the flagon’s spout

On each flagon, there are at least 120 separate pieces of coral – probably from the Mediterranean. They’ve now faded to white, but originally they would have been bright red, giving a striking contrast to the lustrous bronze. You can imagine the flagons standing by blazing firelight, with the flames reflected in the bronze and deepening the red of the coral, while the wine, beer or mead they contained was ceremonially poured for important guests.

The animals on the flagons also tell us a great deal about the people who made them. The curved handle is a lean, elongated dog, stretching forward, fangs bared and holding in its mouth a chain that connects to the stopper. Dogs would have been an essential part of hunting life, and two more, smaller, dogs lie on either side of the lid. All three dogs have their attention focused on a tiny bronze duck that sits right at the end of the spout. It’s a lovely touch, both moving and funny. When somebody poured from the flagon, it would look as though the duck was swimming on a stream of wine, mead or beer.

What would be clear to anyone whose cup was being filled from these flagons was that these luxury goods were local. No piece of Italian design ever looked like this. The extravagant shape, the unique combination of decoration, the animal imagery, all said loud and clear that these were made north of the Alps – examples of a new wave of creativity among craftsmen and designers, a rare confidence in taking elements from different foreign and local sources to forge a new visual language. It was to become one of the great languages of European art.

So, who were these drinkers who could make such wonderful things? We don’t know what they called themselves, because they didn’t write. The only name we have to go on is one given to them by uncomprehending foreigners, the Greeks. They called them ‘Keltoi’; it is the first written reference to the peoples we know as Celts. And this is part of the reason that we call the new art style seen on these flagons Celtic art – although it is very doubtful that the people who made or used this art called themselves Celts, or indeed called the language they spoke Celtic. Sir Barry Cunliffe, former Professor of European Archaeology at the University of Oxford, explains:

The relationship between Celtic art and people we call Celts is very complex. In most of the areas where Celtic art developed and was used, people spoke the Celtic language. That doesn’t mean to say that they thought of themselves as Celts or that we can give them that sort of ethnic identity, but they probably spoke the Celtic language, therefore they could communicate with each other. In the area in which Celtic art developed in the fifth century, roughly eastern France and southern Germany, people had probably been speaking the Celtic language for a long time.

The people we call Celts today live far to the west of the Rhine Valley where our flagons were made – in Brittany, Wales, Ireland and Scotland – but throughout these Celtic lands we find artistic traditions that echo the decoration on the Basse-Yutz Flagons. What has since the nineteenth century been called Celtic art connects our two ornate flagons with the Celtic crosses, the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels, made in Ireland and Britain more than a thousand years later. In metalwork and stone-carving, inlays and manuscript illumination, it’s possible to trace the legacy of a language of decoration, shared across much of western and central Europe, including the British Isles.

But this is no easy lineage to interpret. The problem of understanding the ancient Celts is that we are looking at a fifth-century Greek stereotype, compounded by a much later nineteenth-century British and Irish one. The Greeks constructed an image of the ‘Keltoi’ as a barbaric, violent people. That ancient typecasting was replaced a couple of hundred years ago by an equally fabricated image of a brooding, mystical Celtic identity, which was far removed from the greedy practicalities of the Anglo-Saxon industrial world – the romanticized ‘Celtic Twilight’ of Ossian and Yeats. In the twentieth century it did a great deal to shape the idea of Ireland. Since then, especially in Scotland and Wales, being Celtic has taken on further constructed connotations of national identity.

The idea of a Celtic identity, although strongly felt and articulated today by many, turns out on investigation to be disturbingly elusive, unfixed and changing. The challenge when looking at objects like the Basse-Yutz Flagons is how to get past those distorting mists of nationalist myth-making and let the objects speak as clearly as possible about their own place and their own distant world.

Olmec Stone Mask

900–400

BC

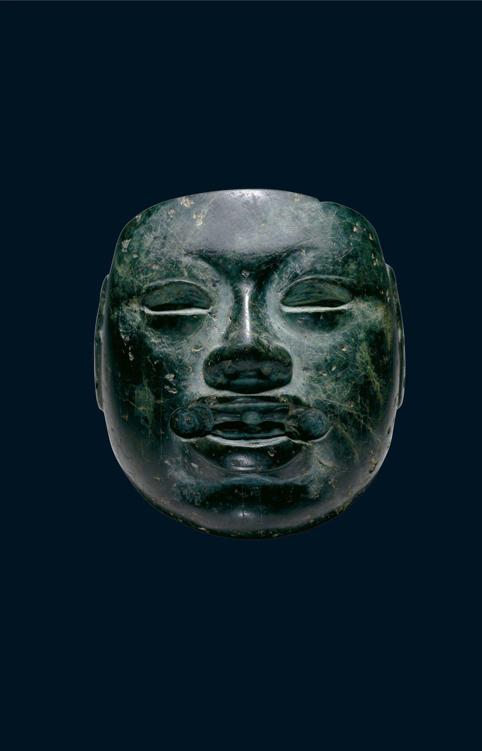

The people who made this mask were the Olmec, who ruled in what is now Mexico for around a thousand years, from 1400 to 400

BC

. They’ve been called the mother culture – the

cultura madre

– of Central America. The mask is made in polished green stone, and unlike a sculpted head it’s hollowed out at the back. The white, snake-like streaks in the dark stone give it its name, ‘serpentine’. When you look closely, you can see the face has been pierced, and has been ritually scarred.

The previous objects in this world history have taken me along the royal roads of the Persian Empire, into mythical battles in Athens and to some heavy drinking in northern Europe. Each object has shown how the people who made it defined themselves and the world around them about 2,500 years ago. In Europe and Asia it is striking that self-definition was usually in distinction to others – partly by imitation but usually in opposition. Now I’m looking at an object from the Americas, from the lowland rainforests of south-east Mexico, and this Olmec face mask shows me a culture looking only at itself. It’s an aspect of the great continuity of Mexican culture, a culture as old as that of Egypt.

Most of us in Britain don’t learn a lot about Central American civilizations at school; we may be taught about the Parthenon, and even perhaps Confucius, but we don’t on the whole learn a lot about the great civilizations occurring at the same time in Central America. Yet the Olmecs were a highly sophisticated people, who built the first cities in Central America, mapped the heavens, developed the first writing and probably evolved the first calendar there. They even invented one of the world’s earliest ball games – which the Spanish would encounter about 3,000 years later. It was played using rubber balls – rubber being readily available from the local tropical gum trees – and although we don’t know what the Olmecs called themselves, it’s documented that the Aztecs called them the people of Olmen, meaning ‘the rubber country’.

It is relatively recently that the Olmec civilization was uncovered from the jungles of Mexico; only after the First World War were their sites, their architecture and above all their sculptures found and investigated. Discovering when the Olmecs lived took even longer. From the 1950s new techniques of radiocarbon dating allowed archaeologists to suggest dates for the buildings and therefore for the people that lived in them. The results showed that this great civilization flourished about 3,000 years ago. The discovery of this ancient and long-lived culture has had a profound effect on modern Mexican notions of identity. I asked the celebrated Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes what it means to him:

It means that I have a continuity of culture that is quite astonishing. Many Latin Americans who are merely migrants from European countries, or do not have a strong Indian culture behind them, don’t appreciate the extraordinary strength of the culture of Mexico, which begins a very long time ago in the twelfth or thirteenth century before Christ.

We consider ourselves heirs to all these cultures. They are a part of our make-up, a part of our race. We are basically a Mestizo country, Indian and European. The Indian culture has infiltrated into our literature, into our painting, into our habits, into our folklore. It is everywhere. It is a part of our heritage, as much as the Spanish culture, which for us is not only Iberian but also Jewish and Moorish. So Mexico is a compound of many civilizations, and part of them are the great Indian civilizations of the past.

So who were the Olmecs? Whose face does this mask show, and how was it worn? Olmec masks have been intriguing historians for a long time. Scrutinizing their features, many scholars believed that they were looking at Africans, Chinese or even Mediterranean people, who had come to colonize the New World. I suppose if you look at our mask, wanting to see an African or a Chinese face, you can just about persuade yourself that you can; but the features are, in fact, entirely characteristic of Central American people. This face is one that can still be seen in the descendants of the Olmecs living in Mexico today. But the desire to discover European or Asian elements in ancient American societies, to find evidence of ancient links and influences, is deep and it is revealing. The similarities between the cultures of the old and the new worlds are so strong – both produced pyramids and mummification, temples and priestly rituals, social structures and buildings that function in similar ways – that scholars for a long time found it hard to believe that these American cultures could have evolved in isolation. But they did.

At only 13 centimetres (5 inches) high, the mask is obviously far too small to have been worn over anybody’s face, and it’s much more likely that it would have been worn round the neck or in a headdress, possibly for some kind of ceremony. Small holes have been bored at the edges and at the top of the mask, so that you could easily fasten it with a bit of twine or thread. On either cheek you can see what, to my European eyes, look like two candles standing on a holder. To the eyes of the Olmec specialist Professor Karl Taube, the four verticals most probably stand for the cardinal points of the compass, and they suggest to him that this may be the likeness of a king:

We have great colossal heads, we have thrones, portraits of kings and, very often, the concept of centrality, placing the king at the centre of the world. And so, on this finely carved serpentine mask, we see four elements on the cheek which are probably the four cardinal directions. For the Olmec, of major concern were the world directions and world centre, with the king being the pivotal world axis in the world centre.

As well as honouring a wide range of gods, the Olmecs also revered their ancestors – so it’s possible that this mask with its particular features and markings might well represent a historic king or a legendary ancestor. Karl Taube has observed that in many sculptures we find what seems to be the same person’s face, with incisions that represent tattooing; as this pattern is seen often, he suggests there might have been an actual individual who had this facial marking. Olmec specialists refer to him as the ‘Lord of the double scroll’.