A History of the World in 100 Objects (22 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

In domestic ceremonies, families offered food and drink to their watchful dead; but on a grander scale governments offered them to the mighty gods. If the

gui

addressed the ancestors and the world of the past, it also emphatically asserted authority in the present – at a troubled transitional moment for China, when the link between heavenly and earthly authorities was supremely important.

The Shang Dynasty, which came to power in about 1500

BC

, had seen the growth of China’s first large cities. Their last capital, at Anyang on the Yellow River in north China, covered an area of 30 square kilometres (10 square miles) and had a population of 120,000 – at the time it must have been one of the largest cities in the world. Life in Shang cities was highly regulated, with twelve-month calendars, decimal measurement, conscription and centralized taxes. As centres of wealth, the cities were also places of outstanding artistic production, in ceramics, jade and, above all, bronze. But then, about 3,000 years ago, from the Mediterranean to the Pacific, existing societies collapsed and were replaced by new powers.

The Shang, which had been in power for around 500 years, was toppled by a new dynasty, the Zhou, who came from the west, from the steppes of central Asia. Like the Kushites of Sudan who conquered Egypt at roughly the same time, the Zhou were a people from the edge who challenged and overthrew the old-established, prosperous centre. They ultimately took over the entire Shang kingdom and, again like the Kushites, appropriated not just the state they had conquered but its history, imagery and rituals too. They continued to support artistic production of many different kinds, and they continued the ritual central to Chinese political authority of elaborate feasting with the dead using vessels like our

gui

. This was in part a public assertion that the gods endorsed the new regime.

The inscription inside the

gui

commemorates the Zhou’s suppression of a Shang rebellion

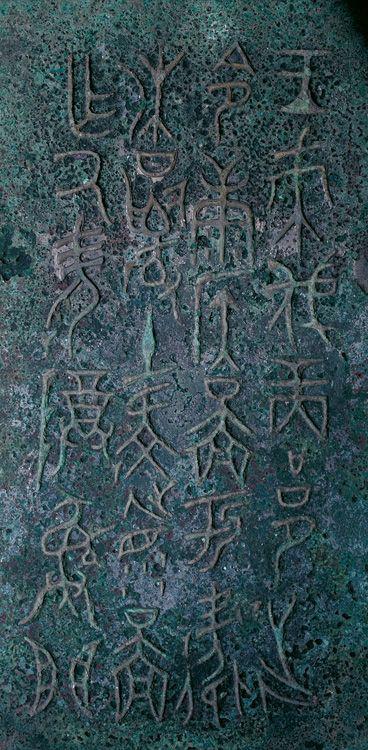

If you look inside the

gui

there is a surprise, which makes it into an instrument of power as well as an object of ritual. At the bottom, where it would have normally been hidden by food when in use, there is an inscription in Chinese characters, not unlike those still used today, which tells us that this particular bowl was made for a Zhou warrior, one of the invaders who overthrew the Shang Dynasty. At this date, any formal writing is prestigious, but writing in bronze carries a very particular authority. The inscription tells us of a significant battle in the Zhou’s ultimate triumph over the Shang:

The King, having subdued the Shang country, charged the Marquis K’ang to convert it into a border territory to be the Wei state. Since Mei Situ Yi had been associated in effecting this change, he made in honour of his late father this sacral vessel.

So the man who commissioned the

gui

, Mei Situ Yi, did so in order to honour his dead father and at the same time, as a loyal Zhou, commemorated the quashing of a Shang rebellion in about 1050

BC

by the Zhou king’s brother, the Marquis K’ang. As writing on bamboo or wood has perished, bronze inscriptions of this kind are now our principal historical source, and through them we can reconstruct the continued tussling between the Shang and the Zhou.

It is not at all clear why the smaller and much less technically sophisticated Zhou were able to defeat the powerful and well-organized Shang state. They seem to have had a striking ability to absorb and to shape allies into a coherent attacking force, but above all they were buoyed up by their faith in themselves as a chosen people. In first capturing and then ruling the Shang kingdom they saw themselves – as so many conquerors do – as enacting the will of the gods; so they fought with the confidence born of knowing that they were the rightful inheritors of the land. But – and this was new – they articulated this belief in the form of a controlling concept that was to become a central idea in Chinese political history.

The Zhou were the first to formalize the idea of the ‘Mandate of Heaven’, the Chinese notion that heaven blesses and sustains the authority of a just ruler. An impious and incompetent ruler would displease the gods, who would withdraw their mandate from him. Accordingly it followed that the defeated Shang must have lost the Mandate of Heaven, which had passed to the virtuous, victorious Zhou. From this time on, the Mandate of Heaven became a permanent feature of Chinese political life, underpinning the authority of rulers or justifying their removal. Dr Wang Tao, an archaeologist at the University of London, describes it this way:

The mandate transformed the Zhou, because it allowed them to rule other people. The killing of a king or senior member of the family was the most terrible crime possible, but any crime against authority could be justified by the excuse of ‘the Mandate of Heaven’. The concept equates in its totemic quality to the Western idea of democracy. In China if you offended the gods, or the people, you would see omens in the skies – thunder, rain, earthquakes. Every time that China had an earthquake, its political rulers were scared, because they interpreted it as a reaction to some kind of offence against the Mandate of Heaven.

Gui

like this have been found over a wide swathe of China, because the Zhou conquest continued to expand until it covered nearly twice the area of the old Shang kingdom. It was a cumbersome state, with fluctuating levels of territorial control. Nonetheless, the Zhou Dynasty lasted for as long as the Roman Empire, indeed longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history.

And as well as the Mandate of Heaven, the Zhou bequeathed one other enduring concept to China. Three thousand years ago they gave to their lands the name of ‘Zhongguo’: the ‘Middle Kingdom’. The Chinese have thought of themselves as the Middle Kingdom, placed in the very centre of the world, ever since.

Paracas Textile

300–200

BC

Looking at clothes is a key part of any serious look at history. But, as we all know to our cost, clothes don’t last – they wear out, they fall apart and what survives gets eaten by the moths. Compared with stone, pottery or metal, clothes are pretty well non-starters in a history of the world told through ‘things’. So regrettably, but not surprisingly, it’s only now, well over a million years into our story, that we’re coming to clothes and to all that they can tell us about economics and power structures, climate and customs, and how the living view the dead. Nor is it surprising that, given their vulnerability, the textiles we are looking at are fragments.

The South America of 500

BC

, like the Middle East, was undergoing change. The South Americans’ artefacts, however, were on the whole much less durable than a sphinx; there, it was textiles that played a central part in the complex public ceremonies. We’re learning new things all the time about the Americas at this date, but, as there are no written sources, much is still very mysterious, compared, for example, with what we know about Asia, belonging to a world of behaviour and belief that we still struggle to interpret from fragmentary evidence like these pieces of cloth, well over 2,000 years old.

In the British Museum these textiles are usually kept in specially controlled conditions, and never exposed to ordinary light and humidity for long. The first thing that strikes you about them is their extraordinary condition. They’re each about 10 centimetres (3 or 4 inches) long, and they’re embroidered in stem-stitch using wool, from either llamas or alpacas, we’re not sure which – both animals are native to the Andes and were soon domesticated. The figures have been very carefully cut out from a larger garment – a mantle or a cape, perhaps. They are strange beings, not entirely human in form, which seem to have talons instead of hands, and claws for feet.

At first glance you might find these figures rather charming, as they appear to be flying through the air with their long pigtails or top knots trailing behind them … but when you look more closely, they are disconcerting, because you can see that they are wielding daggers and clasping severed heads. Perhaps the most striking thing about them, though, is the intricacy of the sewing and the surviving brilliance of the colours, with their blues and pinks, yellows and greens, all sitting very carefully judged next to one another.

These jewel-like scraps of cloth were found on the Paracas peninsula, about 240 kilometres (150 miles) south of modern Lima. In the narrow coastal strip between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific, the people of Paracas produced some of the most colourful, complex and distinctive textiles that we know. These early Peruvians seem to have put all their artistic energies into textiles. Embroidered cloth was for them roughly what bronze was for the Chinese at the same date: the most revered material in their culture, and the clearest sign of status and authority. These particular pieces of cloth have come down to us because they were buried in the dry desert conditions of the Paracas peninsula. Textiles from ancient Egypt have survived from the same period, in similar dry climates thousands of miles away. Like the Egyptians, the Peruvians mummified their dead. And in Peru, as in Egypt, textiles were intended not just for wearing in daily life but also for clothing the mummies: that was the purpose of the Paracas textiles.

The Canadian weaver and textile specialist Mary Frame has been studying these Peruvian masterpieces for over thirty years, and she finds in these funeral cloths an extraordinary organization at work:

Some of the wrapping cloths in these mummy bundles were immense – one was 87 feet long. It would have been a social enactment, a happening, to lay out the yarns to make these cloths. You can have up to 500 figures on a single textile, and they are organized in very set patterns of colour repetition and symmetry. The social levels were reflected in cloth to a tremendous degree. Everything about textiles was controlled – what kind of fibre, colours, materials could be used and by what groups. There has always been a tendency to do that in a stratified society – to use something major, like textiles, to visibly reflect the levels in the society.

There was no writing that we know of at this time in Peru, so these textiles must have been a vital part of this society’s visual language. The colours must have been electrifying against the everyday palette of yellow and beige hues that dominated the landscape of the sandy Paracas peninsula. They were certainly very difficult colours to achieve. The bright red tones were extracted from the roots of plants, while the deep purples came from molluscs gathered on the shore. The background cloth would have been cotton, spun and dyed before being woven on a loom. Figures were outlined first, and then the details – like clothes and facial features – were filled in in different colours with exquisite precision, presumably by young people, as you need perfect eyesight for stitching like this.

Production would have required coordinating large numbers of differently skilled labourers – the people who reared the animals for the wool or who grew the cotton, those who gathered the dyes, and then the many who actually worked on the textiles themselves. A society that could organize all this, and devote so much energy and resource to materials for burial, must have been both prosperous and very highly structured.

Making the mummy bundles, in other words preparing the Paracas elite for burial, involved an elaborate ritual. The naked corpse was first bound with cords to fix it in a seated position. Wrapped pieces of cotton or occasionally gold were put in the mouth, and grander corpses had a golden mask strapped to the lower half of their face. After this the body was wrapped in a large embroidered textile – our fragments must come from one of these – and the encased body was then seated upright in a big shallow basket containing offerings of shell necklaces, animal skins, bird feathers from the Amazonian jungle and food, including maize and peanuts. Then body, offerings and basket, all together, were wrapped in layers of plain cotton cloth to form one giant conical mummy bundle, sometimes up to 1.5 metres (5 feet) wide.