A History of the World in 100 Objects (11 page)

Read A History of the World in 100 Objects Online

Authors: Neil MacGregor

In the last few chapters, we have been looking at the way we now think humans began to domesticate animals and to cultivate plants. As a consequence, they started to eat new things and to live differently – in short, they settled down. It had long been assumed that pottery must have coincided with this shift to a more sedentary life. But we know now that, in fact, the earliest pottery was made around 16,500 years ago, in what most experts recognize as the Old Stone Age, when people were still moving about, hunting big-game animals. Nobody really expected to find pottery quite as early as that.

You’ll find pots all around the world, and in museums all around the world. In the Enlightenment gallery of the British Museum there are lots of them – Greek vases with heroes squabbling on them, Ming bowls from China, full-bellied African storage jars and Wedgwood tureens. They are an essential part of any museum collection, for human history is told and written perhaps more in pots than in anything else. As Robert Browning put it: ‘Time’s wheel runs back or stops: Potter and clay endure.’

The world’s first pots were made in Japan. This particular one, made there about 7,000 years ago in a tradition that even then was almost 10,000 years old, is initially quite dull to look at. It’s a simple round pot about the shape and size of a bucket that children might play with on the beach. It is made of brown-grey clay and is about 15 centimetres (6 inches) high. When you look more closely, you can see that it was built up with coils of clay and then fibres were pressed into the outside, so that when you hold it you feel as though you are actually holding a basket. This small Jomon pot looks and feels like a basket in clay.

The basket-like markings on this and other Japanese ceramics of the same period are in a cord pattern. That’s what the name ‘Jomon’ means in Japanese, but the word has come to be used not just for the pots but also for the people who made them, and even the whole historic period in which they lived. It was these Jomon people living in what is now northern Japan who created the world’s first pots. Simon Kaner, of the University of East Anglia, a specialist in ancient Japanese culture, puts them in context:

In Europe we’ve always assumed that people who’ve made pottery were farmers, and that it was only through farming that people were able to stay in one place, because they would be able to build up a surplus on which they could then subsist through the winter months, and it was only if you were going to stay in one place all the year round that you’d be making pottery, because it’s an awkward thing to carry around with you. But the Japanese example is really interesting, because here we have pottery being made by people who were not farmers. It’s some of the best evidence we have from prehistory anywhere in the world that people who subsisted on fishing, gathering nuts and other wild resources, and hunting wild animals also had a need for cooking pots.

The Jomon way of life seems to have been pretty comfortable. They lived near the sea and they relied on fish as a main source of food – food that came to them, so they did not have to move around as land-roaming hunter-gatherers did. They also had easy access to abundant plants with nuts and seeds, so there was no imperative to domesticate animals or to cultivate particular crops. Perhaps because of this plentiful supply of fish and food, farming took a long time to establish itself in Japan compared to the rest of the world. Simple agriculture, in the form of rice cultivation, arrived in Japan only 2,500 years ago – very late, on the international scale; but in pots the Japanese were in the lead.

Before the invention of the pot, people stored their food in holes in the ground or in baskets. Both methods were vulnerable to insects and to all kinds of thieving creatures, and the baskets were also subject to wear and weather. Putting your food in sturdy clay containers kept freshness in and mice out. It was a great innovation. But in the shape and texture of the new pots the Jomon did not innovate: they looked at what they already had – baskets. And they decorated them magnificently. Professor Takashi Doi, Senior Archaeologist at the Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan, describes the patterns they produced:

The decorations were derived from what they saw around them in the natural world – trees, plants, shells, animal bones. The basic patterns were applied using twisted plant fibres or twisted cords, and there was an amazing variety in the ways you could twist your cords – there is an elaborate regional and chronological sequence that we have identified. Over the years of the Jomon period we can see over 400 local types or regional styles. You can pin down some of these styles to 25-year time slots, because they were so specific with their cord markings.

The Jomon clearly relished this elaborate aesthetic game, but they must also have been thrilled at the practical properties of their new leak-proof, heat-resistant kitchenware. Their menu would have included vegetables and nuts, but in their new pots they also cooked shellfish – oysters, cockles and clams. Meat too was pot-roasted or boiled – Japan appears to be the birthplace of the soup and the home of the stew. Simon Kaner explains how this style of cooking now helps us to date the material:

We’re quite lucky they weren’t very good at washing up, these guys – and so they’ve left some carbonized remains of foodstuffs inside these pots, there are black deposits on the interior surfaces. In fact, some of the very early ones that are now dated to about 14,000 years ago – there are black incrustations, and it’s that carbonized material that has been dated – we think they were probably used for cooking up some vegetable materials. Perhaps they were cooking up fish broths? And it’s possible they were cooking up nuts, using a wide range of nuts – including acorns – that you need to cook and boil for a long time before you can actually eat them.

This is an important point – pots change your diet. New foods become edible only once they can be boiled. Heating shellfish in liquid forces the shells to open, making it easier to get at the contents, but also, no less importantly, it sorts out which are good and which are bad – the bad ones stay closed. It’s alarming to think of the trial and error involved in discovering which foods are edible, but it’s a process that is greatly speeded up by cooking.

The Jomon hunter-gatherer way of life, enriched and transformed by the making of Jomon pottery, did not change significantly for more than 14,000 years. Although the oldest pots in the world were made in Japan, the technique did not spread from there. Like writing, pottery seems to have been invented in different places at different times right across the world. The first known pots from the Middle East and North Africa were made a few thousand years after the earliest Jomon pots, and in the Americas it was a few thousand years after that. But almost everywhere the invention of the pot was connected with new cuisines and a more varied menu.

Nowadays Jomon pots are used as cultural ambassadors for Japan in major exhibitions around the world. Most nations, when presenting themselves abroad, look back to imperial glories or invading armies. Remarkably, technological, economically powerful Japan proudly proclaims its identity in the creations of the early hunter-gatherers. As an outsider I find this very powerful, for the Jomon’s meticulous attention to detail and patterning, the search for ever-greater aesthetic refinement and the long continuity of Jomon traditions seem already very Japanese.

But the story of our small Jomon pot doesn’t end here, because I haven’t yet described what is perhaps the most extraordinary thing of all about it – that the inside is carefully lined with lacquered gold leaf. One of the fascinating aspects of telling a history through objects is that they go on to have lives and destinies never dreamt of by those who made them – and that’s certainly true of this pot. The gold leaf was applied somewhere between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, when ancient pots were being discovered, collected and displayed by Japanese scholars. It was probably a wealthy collector who had the inside of the pot lacquered with a thin layer of gold. After 7,000 years of existence our Jomon pot then began a new life – as a

mizusashi

, or water jar, for that quintessentially Japanese ritual, the Tea Ceremony.

I don’t think its maker would have minded.

The First Cities and States

4000–2000

BC

The world’s first cities and states emerged in the river valleys of North Africa and Asia about 5,000 to 6,000 years ago. In what are today Iraq, Egypt, Pakistan and India, people came together to live for the first time in settlements larger than villages, and there is evidence of kings, rulers and great inequalities of wealth and power; at this time, too, writing first developed as a means of controlling growing populations. There are important differences between these early cities and states in the three regions: in Egypt and Iraq they were very warlike, in the Indus Valley apparently peaceable. In most of the world, people continued to live in small farming communities which were, however, often part of much larger networks of trade stretching across wide regions.

King Den’s Sandal Label

AROUND

2985

BC

There’s a compelling, beguiling showbiz mythology of the modern big city – the energy and the abundance, the proximity to culture and power, the streets that just might be paved with gold. We’ve seen it and we’ve loved it, on stage and on screen. But we all know that in reality big cities are hard. They’re noisy, potentially violent and alarmingly anonymous. We sometimes just can’t cope with the sheer mass of people. And this, it seems, is not entirely surprising. Apparently, if you look at how many numbers we’re likely to store in our mobile phone, or how many names we’re likely to list on a social networking site, it’s rare even for city dwellers to exceed a couple of hundred. Social anthropologists delightedly point out that this is the size of the social group we would have had to handle in a large Stone Age village. According to them, we’re all trying to cope with modern big-city life equipped only with a Stone Age social brain. We all struggle with anonymity.

So how do you lead and control a city or a state where most people don’t know each other, and you can interact personally with only a very small percentage of the inhabitants? It’s been a problem for politicians for more than 5,000 years, ever since the groups we live in exceeded the size of a tribe or village. The world’s first crowded cities and states grew up in fertile river valleys: the Euphrates, the Tigris and the Indus. This chapter’s object is associated with the most famous river of them all, the Nile. It comes from the Egypt of the pharaohs, where the answer to the question of how to exert leadership and state control over a large population was quite simple: force.

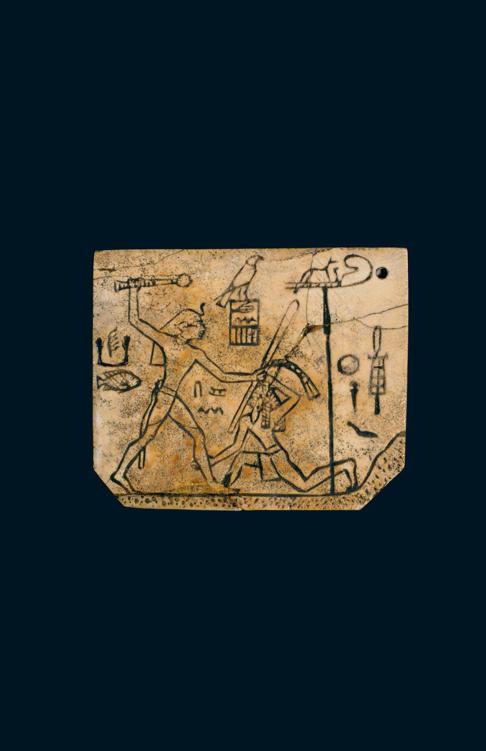

If you want to investigate the Egypt of the pharaohs, the British Museum gives you a spectacular range of choices – monumental sculptures, painted mummy cases, and much more – but I’ve chosen an object that came quite literally from the mud of the Nile. It’s made from a tusk of a hippo, and it belonged to one of Egypt’s first pharaohs – King Den. Perversely for an object that’s going to let us explore power on a massive scale, it is tiny.

It is about 5 centimetres (2 inches) square, it’s very thin, and it looks and feels a bit like a modern-day business card. In fact, it’s a label that was once attached to a pair of shoes. We know this because on one side is a picture of those shoes. This little ivory plaque is a name tag for an Egyptian pharaoh, made to accompany him as he set off to the afterlife, a label which would identify him to those he met. Through it, we’re immediately close to these first kings of Egypt – rulers, around 3000

BC

, of a new kind of civilization that would produce some of the greatest monumental art and architecture ever made.

The nearest modern equivalent I can think of to this label is the ID card that people working in an office now have to wear round their necks to get past the security check – though it’s not immediately clear who was meant to read these Egyptian labels, whether they’re aimed at the gods of the afterlife or perhaps ghostly servants who might not know their way around. The images themselves are made by scratching into the ivory and then rubbing a black resin into the incisions, making a wonderful contrast between the black of the design and the cream of the ivory.

Before the first pharaohs, Egypt was a divided country, split between the east–west coastal strip of the Nile Delta, facing the Mediterranean, and the north–south string of settlements along the river itself. With the Nile flooding every year, harvests were plentiful, so there was enough food for a rapidly growing population and, frequently, surplus to trade with. But there was absolutely no extra fertile land beyond the flooding area, and as a result the ever more numerous people fought bitterly over the limited amount of land. Conflict followed conflict, with the people from the Delta eventually being conquered by the people from the south just before 3000

BC

. This united Egypt was one of the earliest societies that we can think of as a state in the modern sense, and, as one of its earliest leaders, King Den had to address all the problems of control and coordination that a modern state has to confront today.