Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (93 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The following morning a more reliable force of Canadian Fencibles and Voltigeurs arrives. The latter unit consists not of habitants but of voyageurs, lumbermen, and city-bred youths. They have been drilled all winter like regulars by their leader, a thirty-five-year-old career soldier, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry. They wear smart grey uniforms and fur hats and are used to fighting in their bare feet.

De Salaberry, who has been given charge of the Châteauguay frontier by his superior, the Swiss-born Major-General de Watteville, is that unique product of Lower Canada, the French-Canadian aristocrat. But he is no fop. De Rottenburg refers to him as “my dear Marquis of cannon powder.” Short in stature, big-chested and muscular, he is a strict disciplinarian—brusque, impetuous, often harsh with his men. Dominique Ducharme, the victor at Beaver Dams, now back in Lower Canada, cannot forgive him for dispatching him to track down six deserters, whom he ordered shot. (Ducharme, had he known what would be their fate, would have let them escape.) De Salaberry’s Voltigeurs, however, admire their leader because he is fair minded.

This is our major, [they sing]

The embodiment of the devil

Who gives us death.

There is no wolf or tiger

Who could be so rough;

Under the openness of the sky

There is not his equal.

In the de Salaberry vocabulary, one word takes precedence over all others: honour. He cannot forget his father’s remark to Prevost’s predecessor, Sir James Craig. The elder de Salaberry openly opposed Craig, who wanted to destroy the rights of French Canadians. When Craig threatened to remove his means of livelihood, Ignace de Salaberry retorted: “You can, Sir James, take away my bread and that of my family, but my honour—never!”

The Voltigeurs no doubt know the story of the scar their colonel carries on his brow. It goes back to his days in a mixed regiment in the West Indies, when a German duellist killed his best friend.

The duellist: “I come just now from dispatching a French Canadian into another world.”

De Salaberry: “We are going to finish lunch and then you will have the pleasure of dispatching another.”

But it is the German who is dispatched, de Salaberry merely scarred.

He has been a soldier since the age of fourteen; three younger brothers have already died in the service. His father’s patron and his own was the Duke of Kent, father of a future queen. The Duke prevented him from making an unfortunate marriage; the bride he later chose is a seigneur’s daughter.

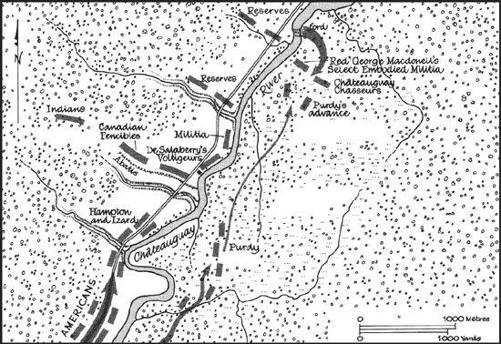

For weeks, de Salaberry has been spying on Hampton’s pickets at Châteauguay Four Corners. Now he is prepared to meet the full force not far from the confluence of the Châteauguay and the English River.

He has chosen his position with care. Half a dozen ravines cut their way through the sandy soil at right angles to the Châteauguay

River. These will be his lines of defence. The first three are only two hundred yards apart, the fourth half a mile to the rear. At least two more lie some distance downriver near La Fourche, where Major-General de Watteville’s reserves and headquarters will be stationed.

By midday on October 22, de Salaberry has his axemen constructing breastworks of felled trees and tangled branches on the forward tip of each ravine. A mile or more in front of the leading ravine—a coulee forty feet deep on Robert Bryson’s farm—they build a vast abatis extending in an arc from the river’s gorge on the left to a swamp in the forest on their right.

The axemen are still hacking down trees and piling up slash when de Salaberry is reinforced in a dramatic fashion. In Kingston, on October 21, Sir George Prevost had decided to send a battalion of Select Embodied Militia—a mixed bag of French-Canadian and Scottish farmers—to Châteauguay. He called on their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel George Macdonell, to ask how soon the battalion could be under way.

“As soon as my men have done dinner,” replied the Colonel, who is known through the county as Red George to distinguish him from a score of other Glengarry Macdonells.

Now Prevost has come post-haste to Châteauguay where, to his astonishment, he encounters Red George. The battalion has made the trip in just sixty hours without a man absent.

That same day, October 24, as Hampton’s main body moves up along the road his engineers have hacked through the bush, a spy watches them go by and carefully counts the guns, the wagons, and the troops, immediately sending detailed reports to the British.

More than fourteen hundred of Hampton’s militiamen, he writes, have refused to cross the border. The Americans are badly clothed, having so little winter gear that they have had to cast lots for greatcoats. The Virginians are not used to the Canadian weather. One regiment of a thousand Southerners has lost half its force to “a kind of distemper.” He has also heard a report that Major-General Wilkinson is bringing his army down the St. Lawrence by boat and plans to join Hampton in an assault on Montreal.

Now the British are aware of the full American strategy. Hampton has upwards of four thousand men assembled at Spears’s farm. All that stands between him and the St. Lawrence are the sixteen hundred militiamen seven miles downriver. The brunt of the attack will be borne by de Salaberry’s three hundred Canadian Voltigeurs and Fencibles manning the forward ravines. They wait behind the tangle of roots and branches, knowing that they are heavily outnumbered and outgunned. The spy has counted nine pieces of field artillery, a howitzer, and a mortar and suspects there is more moving toward the Canadian lines by an alternative route.

Who is this secret agent who seems to know everything that is going on at Spears’s farm and Four Corners? He is, of course, David Manning, the Loyalist farmer, whom Wade Hampton believes to be safely behind bars at Greenbush. But Hampton has not reckoned on the uncertain loyalties of the border people. He does not know, will never know, that Hollenbeck, his sergeant of the guard, is not only David Manning’s friend and neighbour but also an informant who is perfectly prepared to salute the Stars and Stripes in public while secretly supplying the British with all the information and gossip they require.

SPEARS’S FARM, CHÂTEAUGUAY RIVER, LOWER CANADA, OCTOBER 25, 1813

Major-General Wade Hampton considers the problem of de Salaberry’s defence in depth and realizes he cannot storm those fortified ravines without serious loss. He decides instead on a surprise flanking movement that will take the French Canadians in the rear.

He summons Robert Purdy, Colonel of the veteran U.S. 4th Infantry, and gives him his orders. Purdy will take fifteen hundred elite troops, cross the Châteauguay River at a nearby ford, proceed down the right bank under cover of darkness, bypass de Salaberry’s defences on the opposite shore, recross the river at dawn by way of a second ford, and attack the enemy from behind their lines. Once Hampton hears the rattle of Purdy’s muskets, he will launch

a frontal attack on the abatis, thus catching de Salaberry’s slender force between the claws of a pincer.

It is an ingenious plan on paper, impossible to carry out in practice. Hampton is proposing that Purdy and his men, accompanied by guides, plunge through sixteen miles of thick wood and hemlock swamp in pitch darkness. That would be difficult in familiar territory; here it becomes a nightmare. The guides prove worthless, have, in fact, warned Hampton that they are not acquainted with the country. But Hampton is bewitched by a fixed idea; nothing will swerve him.

The result is disaster. Hampton accompanies the expedition to the first ford, then returns to camp. The night is cold; rain begins to fall; there is no moon. On the far side of the river Purdy’s men flounder into a creek, stumble through a swamp, trip over fallen trees, stagger through thick piles of underbrush. Any semblance of order vanishes.

After two miles the guides themselves are lost. Purdy realizes he cannot continue in the dark. The men spend the night in the rain, shivering in their summer clothing, unable to light a fire for fear of betraying the plan.

At the camp, Hampton receives a rude shock. A letter arrives from the Quartermaster General relaying Armstrong’s instructions to build huts for the army’s winter quarters at Four Corners—south of the border.

Winter quarters at Four Corners!

Hampton has been expecting to winter at Montreal. The order can have one meaning only: Armstrong doubts that the expedition will reach its objective. The fight goes out of Hampton. Heartsick, he considers recalling Purdy’s force but realizes that in the black night it cannot be found.

Dawn arrives, wan and damp, the dead leaves of autumn drooping wetly from the trees. In a tangle of brush and swamp, Purdy shakes his men awake. On the opposite bank, the American camp is all abustle, the forward elements already in motion along the wagon road that leads to the French-Canadian position.

In spite of his intelligence system, de Salaberry is not expecting an attack this morning. A party of his axemen, guarded by forty

soldiers, is strengthening the abatis a mile in front of the forward ravine when, at about 10

A.M

., the first Americans come bounding across the clearing, firing their muskets. De Salaberry, well to the rear, hears the staccato sounds of gunfire, moves up quickly with reinforcements. The workmen have scattered, and the Americans, cheering lustily, push forward, only to be halted by musket fire.

The Battle of Châteauguay: Phase 1

De Salaberry—a commanding figure in his grey fur-trimmed coat—moves forward on the abatis, climbs up on a large hemlock that has been uprooted by the wind, and, screened from enemy view by two large trees, watches the blue line of Americans moving down the river road toward him. The firing has sputtered out; the expected attack does not come.

Hampton is waiting to hear from Purdy across the river. The Americans settle down to cook lunch. On the Canadian side of the abatis a company of Beauharnois militia kneel in prayer and are told by their captain that having done their duty to their God, he now expects they will do their duty to their King.

Meanwhile, de Salaberry’s scouts have discovered Purdy’s presence on the east bank of the river—a few stragglers emerging briefly

from the dense woods along the far bank. Purdy is badly behind schedule; his force of fifteen hundred has got no farther than a point directly across from de Salaberry’s forward position. Back goes word to Red George Macdonell, who has been given the task of guarding the ford in the rear. Macdonell sends two companies of his Select Embodied Militia across the river to reinforce a small picket of Châteauguay Chasseurs who, despite their formidable title, are untrained local farmers, co-opted into the Sedentary Militia of Lower Canada.

The Canadians move through the dense pine forest, peering through the labyrinth of naked trunks, seeking the advancing Americans. Purdy’s advance guard of about one hundred men is splashing through a cedar swamp when the two forces meet. Both sides open fire. Macdonell’s men stand fast, but the Chasseurs turn and flee. The American advance party also turns tail and plunges back through the woods where the main body, mistaking them for Canadians, opens fire, killing their own men.

Purdy, thinking the woods full of enemies, attempts to regroup and sends a messenger to Hampton, asking for reinforcements. The courier heads for Spears’s farm, only to discover that Hampton is no longer there, having moved downriver. As a result, Hampton has no idea whether Purdy has achieved his objective. Nor can he tell what is happening on the far bank because of the thickness of the forest.

Finally, at two o’clock Hampton decides to act. He orders Brigadier-General George Izard to attack in line. Izard, another South Carolina aristocrat, is a professional soldier of considerable competence. His well-drilled brigade moves down the road toward the vast tangle of the abatis.

Behind their breastwork, de Salaberry’s Voltigeurs watch as a tall American officer rides forward. After the battle is done, some will claim to remember his cry in French, which will become a legend along the Châteauguay:

“Brave Canadians, surrender yourselves; we wish you no harm!”

At which de Salaberry himself fires, the American drops from his horse, and the battle—such as it is—is joined.

De Salaberry shouts to his bugler to sound the call to open fire. The noise of sporadic musketry mingles with the cries of a small body of Caughnawaga Indians stationed in the woods to the right of the Canadian line. The Americans, firing by platoons, as on a parade ground, pour volley after volley into the woods, believing that the main Canadian force is concentrated there. The lead balls whistle harmlessly through the treetops.

Now Red George Macdonell sounds his own bugles as a signal that he is advancing. Other bugles take up the refrain; de Salaberry sends buglers into the woods to trumpet in all directions until the Americans believe they are heavily outnumbered. Izard hesitates—a fatal error, for he loses momentum. Two other ruses reinforce his misconception about the Canadian strength. Some of Macdonell’s men appear at the edge of the woods wearing red coats, then disappear, reverse their jackets, which are lined with white flannel, and pop out again, appearing to be another corps. In addition, twenty Indians are sent to dash through the forest to the right of the Canadian line, appearing from time to time brandishing tomahawks. The ruse is similar to the one used by Brock against Hull the previous year: the Americans are led to believe that hundreds of savages are lurking in the depths of the woods.