Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (94 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

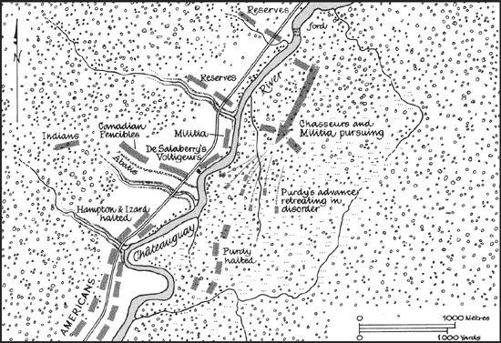

“Defy, my damned ones!” cries de Salaberry. “Defy! If you do not dare, you are not men!”

The battle continues for the best part of an hour, the Americans firing rolling volleys, platoon by platoon, the half-trained Canadians returning the fire raggedly. There are few casualties on either side. Izard does not attempt to storm the abatis.

Now de Salaberry turns his attention to the action on the far side of the river. The two Canadian companies that drove off Purdy’s forward troops have been advancing cautiously toward his position and are now tangling with his main force.

De Salaberry hurries to the river bank, climbs a tree, and begins to shout orders to Captain Charles Daly of the Embodied Militia, speaking in French so the Americans cannot understand him. At the same time he lines up his force of Voltigeurs, Indians, and

Beauharnois militia along his side of the river to fire on Purdy’s men, should they emerge from the woods.

The Battle of Châteauguay: Phase 2

As the two forces face each other in the swampy forest, Daly orders his men to kneel before they fire, a manoeuvre that saves their lives. Purdy’s overwhelming body of crack troops responds with a shattering volley, but most of it passes harmlessly over the Canadians’ heads.

Now Purdy’s force swoops forward on the river flank of the Canadians, determined to take them from the rear. The situation is critical, but as the Americans burst out of the woods and onto the river bank, de Salaberry, watching through his glass, gives the order to fire. The bushes on the far side erupt in a sheet of flame. The Americans, badly mangled, retreat into the forest; exhausted by fourteen hours of struggle, they can fight no more.

A lull comes in the skirmishing. Hampton, sitting his horse on the right of his troops, is in a quandary. A courier has just swum the river with news of Purdy’s predicament. The Major-General is rattled, angry at Purdy for not reporting his position sooner, unaware that the original message has gone astray.

He considers his options. Izard has not attempted to storm the abatis; to do so, Hampton is convinced, would cause heavy casualties. He believes there are five to six thousand men opposing him. In fact, there is only a fraction of that number. De Salaberry has perhaps three hundred men in his advanced position. Macdonell has about two hundred in reserve. The remainder (apart from the two companies across the river) are several miles back at La Fourche, where the English River joins the Châteauguay. These do not number more than six hundred, and none have been committed to battle. De Salaberry, either by accident or by design, has failed to inform Major-General de Watteville of the American advance—a delinquency that nettles his senior and might easily provoke a court martial in the event of failure.

De Salaberry is a bold officer. His defensive position is strong. But it is Hampton’s failure of nerve more than de Salaberry’s brilliance of execution that decides the outcome of the so-called Battle of Châteauguay. In reality, it is no more than a skirmish, with troops on both sides peppering away at each other at extreme range and to little effect. De Salaberry, on his side of the river, has lost three men killed, eight wounded.

Hampton’s heart is not in it. Purdy is bogged down, the afternoon is dragging on, rain is in the offing, twilight but a few hours away. A host of emotions boils up inside the hesitant commander: jealousy of Wilkinson, who will gain all the glory if Hampton, by a victory, helps him to seize Montreal; anger at Armstrong, who he rightly believes is resigned to defeat; and, most telling, a lack of confidence in himself. He does not have the will to win. Much of his force has yet to be engaged in battle. His artillery has not been used. Izard’s brigade has fallen silent. Suddenly, the Major-General sends an order to Purdy to break off the engagement on the right bank and tells his bugler to sound the withdrawal.

De Salaberry’s men watch in astonishment as the brigade retires in perfect order. Oddly, they make no attempt to harass it, waiting instead for a rally that never comes. Their colonel, expecting a renewed attack at any moment, has sent back word to all the houses

along the river to prepare for a retreat and to burn all buildings. It is not necessary.

Of this Colonel Purdy, hidden in the forest, is unaware. As the sun sets he starts to move his wounded across the river on rafts and sends a message to his commander asking that a regiment be detached to cover his own landing. He is shocked and angered to discover that Hampton has already retreated three miles, deserting him without support.

The following morning the once elite detachment straggles into Hampton’s camp, many without hats, knapsacks, or weapons, their clothing torn, half starved, sick with fatigue, their morale shattered. Purdy is thoroughly disgusted. Several of his officers have behaved badly in the skirmish, but when Purdy tries to arrest them for desertion or cowardice, Hampton countermands the order. Purdy reports to the General that someone in the commissary is selling the troops’ rations, but Hampton brushes away the complaint. The sick, in Purdy’s view, are being so badly neglected that many have died from want of medical care. In common with several other officers, Purdy is convinced that Hampton is drinking so heavily that he is no longer able to command.

De Salaberry, meanwhile, feels snubbed by the British high command. Sir George Prevost, who arrived on the field with de Watteville shortly after the victory, is his usual cautious self. The brunt of the struggle has been borne by a handful of French-Canadian militia. One thousand fresh troops, held in reserve, are available to harass the enemy. De Salaberry is eager to do just that, but neither senior commander will allow it. Both are remarkably restrained in their congratulations, perhaps because of de Salaberry’s delinquency in not informing them of the American attack. And de Salaberry himself is embittered because, he believes, he has not been given sole credit for repulsing the invaders. “It grieves me to the heart,” he declares to the Adjutant-General, “to see that I must share the merit of the action.” For Prevost and de Watteville insist on a portion of the glory.

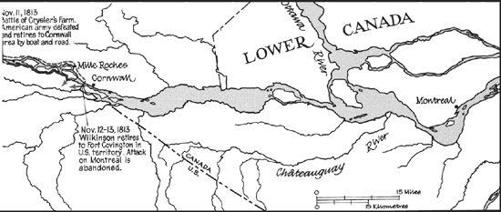

Hampton meanwhile orders his entire force back across the border to Four Corners “for the preservation of the army”—a statement that

would astonish the British, who are convinced that the Americans are planning a second attack. On October 28, Indian scouts confirm Hampton’s decision.

It has been, as de Salaberry asserts in a letter to his father, “a most extraordinary affair.” In this battle in which some 460 troops forced the retirement of four thousand, the victors have lost only five killed and sixteen wounded with four men missing. (The American casualties number about fifty.) It has been a small battle but for Canada profoundly significant. A handful of civilian soldiers, almost all French Canadian, has, with scarcely any help, managed to turn back the gravest invasion threat of the war. Had Hampton managed to reach the St. Lawrence to join with Wilkinson’s advancing army, who would give odds on the survival of Montreal? And with Montreal gone and Upper Canada cut off, the British presence in North America would be reduced to a narrow defensive strip in the lower province. On a military sand table, the battle of Châteauguay seems no more than a silly skirmish. Yet without this victory, what price a Canadian nation, stretching from sea to sea?

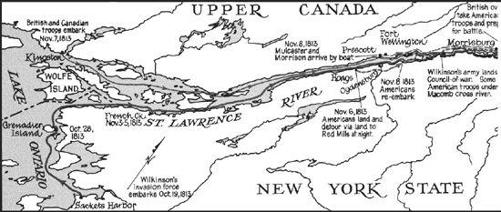

GRENADIER ISLAND, THOUSAND ISLANDS, NEW YORK STATE, OCTOBER 28, 1813

“All our hopes,” James Wilkinson writes to the Secretary of War, “have been very nearly blasted.” Two days have passed since Hampton’s defeat at Châteauguay (a calamity unknown to Wilkinson) and the great flotilla designed to conquer Montreal—or will it be Kingston first?—is still stuck at its rendezvous point. The troops are drenched from the incessant rains, boats are smashed, stores scattered, hundreds sick, scores drunk.

Wilkinson puts the best possible face on these disasters, relying on the Deity to solve his problems:

“Thanks to the same Providence which placed us in jeopardy, we are surmounting our difficulties and, God willing, I shall pass Prescott on the night of the 1st or 2nd proximo, if some unforeseen obstacle does not present to forbid me.”

Unforeseen obstacles have already presented themselves in quantity. On the journey from Sackets Harbor to Grenadier Island—a mere eighteen miles—the flotilla was scattered by gales so furious that great trees were uprooted on the shores. Some boats have not yet arrived.

A third of all the rations have been lost. It is virtually impossible to disentangle the rest from the other equipment. Shivering in the driving rain, the men have torn the oilcloths off the ration boxes for protection, so that the bread becomes soggy and inedible. Hospital stores have been pilfered—the hogsheads of brandy and port wine, which the doctors believe essential for good health, tapped and consumed. The guard is drunk; the officer in charge finds he cannot keep his men sober. The boats are so badly overloaded that they have become difficult to row or steer. Sickness increases daily. One hundred and ninety-six men are so ill that Wilkinson—himself prostrate with dysentery—orders them returned to Sackets Harbor. In spite of the army’s shortage of rations, the American islanders prefer to sell their produce to the British on the north shore. When Jarvis Hanks, a fourteen-year-old drummer boy with the 11th U.S. Infantry, tries to buy some potatoes from a local farmer for fifty cents a bushel, the man refuses, saying he can get a dollar a bushel in Kingston. That night, Hanks and his friends steal the entire crop.

Some of the officers are still half convinced that Wilkinson intends to attack Kingston. Chauncey, in fact, does not learn until October 30 that the Major-General has made up his mind to take the flotilla down the river, joining with Hampton to attack Montreal. The Commodore is, in his own words, “disappointed and mortified.” He clearly does not believe that such a plan has much chance of success, for the season is far advanced.

Three brigades finally set out for the next rendezvous point, at French Creek on the American side of the river directly opposite Gananoque. Brigadier-General Jacob Brown manages to get down the river; bad weather forces the other two back. The bulk of the army arrives on November 3, followed by Wilkinson, now so ill that he has to be carried ashore.

Wilkinson Moves on Montreal, October 31—November 11, 1813

The disillusioned Chauncey, who feels that his navy has been relegated to the position of a mere transport service for the army, is supposed to be guarding the entrance to the St. Lawrence to protect Wilkinson’s flotilla from pursuit by British gunboats. But while Chauncey’s squadron lurks in the south channel, Sir James Yeo’s daring second-in-command, Captain William Howe Mulcaster (the same officer who refused the Lake Erie command) nips down the north channel, evades the Americans, moves down to French Creek, skirmishes with Brown’s brigade, then whips back to Kingston to report at last that Montreal is the enemy’s objective.

The tangle with Mulcaster again delays Wilkinson. The full flotilla does not leave French Creek until November 5.

Providence has at last smiled on the ailing general; the valley of the St. Lawrence is bathed in an Indian summer glow as six thousand men in 350 boats, forming a procession five miles long, slide down the great river, flags flying, brass buttons gleaming, fifes and drums playing, boatmen chorusing. There is one drawback: Mulcaster is not far behind.