Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (89 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Sixteen-year-old Abraham Holmes will remember the sight of Tecumseh standing near the Arnold mill on the morning of October 5,

his hand at the head of his white pony: a tall figure, dressed in buckskin from neck to knees, a sash at his waist, his headdress adorned with ostrich plumes—waiting until the last of his men have passed by and the mill is safe. Holmes is so impressed that he will name his first-born Tecumseh.

Years from now Chris Arnold will describe the same scene to his grandson, Thaddeus. Arnold remembers standing by the mill dam, waiting to spot the American vanguard. It is agreed he will signal its arrival by throwing up a shovelful of earth. But Tecumseh’s eyes are sharper, and he is on his horse, dashing off at full speed, after the first glimpse of Harrison’s scouts. At the farm of Arnold’s brother-in-law, Hubble, he stops to perform a small act of charity—tossing a sack of Arnold’s flour at the front door to sustain the family, which is out of bread.

Lemuel Sherman’s sixteen-year-old son, David, and another friend, driving cows through a swamp, come upon Tecumseh, seated on a log, two pistols in his belt. The Shawnee asks young Sherman whose boy he is and, on hearing his father is a militiaman in Procter’s army, tells him: “Don’t let the Americans know your father is in the army or they’ll burn your house. Go back and stay home, for there will be a fight here soon.”

Years later when David Sherman is a wealthy landowner, he will lay out part of his property as a village and name it Tecumseh.

Billy Caldwell, the half-caste son of the Indian Department’s Colonel William Caldwell, will remember Tecumseh’s fatalistic remarks to some of his chiefs:

“Brother warriors, we are about to enter an engagement from which I shall not return. My body will remain on the field of battle.”

Long ago, when he was fifteen, facing his first musket fire against the Kentuckians, and his life stretched before him like a river without end, he feared death and ran from the field. Now he seems to welcome it, perhaps because he has no further reason to live. Word has also reached him that the one real love of his life, Rebecca Galloway, has married. She it was who introduced him to English literature. There have been other women, other wives; he

has treated them all with disdain; but this sixteen-year-old daughter of an Ohio frontiersman was different. She was his “Star of the Lake” and would have married him if he had only agreed to live as a white man. But he could not desert his people. Now she is part of a dead past, a dream that could not come true, like his own shattered dream of a united Indian nation.

In some ways, Tecumseh seems more Christian than the Christians, with his hatred of senseless violence and torture. He is considerate of others, chivalrous, moral, and, in his struggle for his people’s existence, totally selfless. But he intends to go into battle as a pagan, daubed with paint, swinging his hatchet, screaming his war cry, remembering always the example of his elder brother Cheeseekau, the father figure who brought him up and, in the end, met death gloriously attacking a Kentucky fort, expressing the joy he felt at dying—not like an old woman at home but on the field of conflict where the fowls of the air should pick his bones.

LEMUEL SHERMAN’S FARM, UPPER THAMES, OCTOBER 5, 1813

Procter’s troops, who have had no rations since leaving Dolsen’s, are about to enjoy their first meal in more than twenty-four hours when the order comes to pack up and march—the Americans are only a short distance behind. Some cattle have already been butchered, but there is no time to cook the beef and there are no pans in which to roast it. Nor is there bread. Ovens have been constructed but again the baker has run off. Some of the men stuff raw meat into their mouths or munch on whatever crusts they still have from the last issue; the rest go hungry.

There is worse news. The Americans have seized all the British boats, captured the excess ammunition, tools, stores. The only cartridges the troops have are in their pouches. The officers attempt to conceal that disturbing information from their men.

The army marches two and a half miles. Procter appears and brings it to a halt. Here, with the river on his left and a heavy marsh

on his right, in a light wood of beech, maple, and oak, he will make his stand.

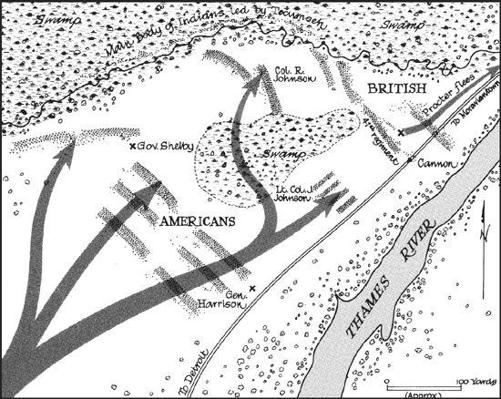

It is not a bad position. His left flank, resting as it does on the high bank of the river, cannot be turned. His right is protected by the marsh. The General expects the invading army to advance down the road that cuts through the left of his position. He plants his only gun—a six-pounder—at this point to rake the pathway. The regulars will hold the left flank. The militia will form a line on their right. Beyond the militia, separated by a small swamp, will be Tecumseh’s Indians.

But why has Procter not chosen to make his stand farther upstream on the heights above Moraviantown, where his position could be protected by a deep ravine and the hundred log huts of the Christian Delaware Indians, who have lived here with their Moravian missionaries since fleeing Ohio in 1792? It is to this village that Procter brought his main ordnance and supplies. Why the sudden change of plan?

Once again the Indians have dictated the battle. They will not fight on an open plain; that is not their style. Procter feels he has no choice but to anticipate their wishes.

His tactics are simple. The British will hold the left while the Indians, moving like a door on a hinge, creep forward through the thicker forest on the right to turn Harrison’s flank.

There are problems, however, and the worst of these is morale. The troops are slouching about, sitting on logs and stumps. They have already been faced about once, marched forward and then back again for some sixty paces, grumbling about “doing neither one thing or another.” Almost an hour passes before they are brought to their feet and told to form a line. This standard infantry manoeuvre is accomplished with considerable confusion, compounded by the fact that Procter’s six hundred men are too few to stand shoulder to shoulder in the accepted fashion. The line develops into a series of clusters as the troops seek to conceal themselves behind trees. Nobody, apparently, thinks to construct any sort of bulwark—entrenchments, earthworks, or a barricade of logs and branches—which

might impede the enemy’s cavalry. No one appears to notice that on the British side of the line there is scarcely any underbrush. But then, all the shovels, axes, and entrenching tools have been lost to the enemy.

The troops stand in position for two and a half hours, patiently waiting for the Americans to appear. They are weak from hunger, exhausted from the events of the past weeks. They have had no pay for six months, cannot even afford soap. Their clothes are in rags, and they have been perennially short of greatcoats and blankets. They are overworked, dispirited, out of sorts. Some have been on garrison duty, far away from home in England, for a decade. They cannot see through the curtain of trees but have heard rumours that Harrison has ten thousand men advancing to the attack. Many believe Procter is more interested in saving his wife and family than in saving them; many believe they are about to be cut to pieces and sacrificed for nothing. And so they wait—for what seems an eternity.

Tecumseh rides up. The men, he tells Elliott, seem to him to be too thickly posted; they will be thrown away to no advantage. Procter obediently robs his line to form a second, one hundred yards behind, with a corps of dragoons in reserve. Now the Shawnee war chief rides down the ragged line, clasping hands with the officers, murmuring encouragement in his own language. He has a special greeting for John Richardson, whom he has known since childhood. Richardson notes the fringed deerskin ornamented with stained porcupine quills, the ostrich feathers (a gift from the Richardson family), and most of all the dark, animated features, the flashing hazel eyes. Whenever in the future he thinks of Tecumseh—and he will think of him often—that is the picture that will remain: the tall sturdy chief on the white pony, who seems now to be in such high spirits and who genially tells Procter, through Elliott, to desire his men to be stout-hearted and to take care the Long Knives do not seize the big gun.

William Henry Harrison, having destroyed Procter’s gunboats and supplies, has crossed the Thames above Arnold’s mill in order to reach the right bank along which the British have been retreating. The water at the ford is so deep that the men hesitate until Perry, in his role as Harrison’s aide, rides through the crowd, shouts to a foot soldier to climb on behind, and dashes into the stream, calling on Colonel Johnson’s mounted volunteers to follow his example. In this way, and with the aid of several abandoned canoes and keel boats, the three thousand foot soldiers are moved across the river in forty-five minutes.

William Whitley, the veteran scout, seeing an Indian on the opposite side, shoots him, swims his horse back across, and scalps the corpse. “This is the thirteenth scalp I have taken,” he tells a friend, “and I’ll have another by night or lose my own.”

As the army forms up on the right bank, a message arrives for Harrison. A spy has reported that the British are not far ahead, aiming for Moraviantown. Harrison rides up to Johnson, tells him that foot soldiers will not be able to overtake Procter until late in the day, asks him to push his mounted regiment forward to stop the British retreat.

“If you cannot compel them to stop without an engagement, why FIGHT them, but do not venture too much,” Harrison orders.

Johnson moves his men forward at a trot. Half a mile from the British line his forward scouts capture a French-Canadian soldier. The prisoner insists that Procter has eight hundred men supported by fourteen hundred Indians. When Johnson reveals he has only one thousand followers, his informant bursts into tears, begs him to retire. But Johnson has no intention of retreating. He sends back a message to Harrison that the British have halted and are only a few hundred yards distant. If they venture to attack, his men will charge them.

Procter does not attack, and the two armies remain within view of one another, motionless, waiting.

A quarter of an hour passes. Harrison rides up, sends Eleazer Wood forward to examine the situation through his spyglass. Behind him, the American column—eleven regiments supported

by artillery—stretches back for three miles. Harrison holds a council of war on horseback. He sees at once that Procter has a good position and divines the British strategy: they will use the Indians on his left on the edge of the morass to outflank him. That he must frustrate. He will attempt to hold the Indians back with a strong force on his left and attack the British line with a bayonet charge through the woods. At the same time Johnson’s mounted men will splash through the shallow swamp that separates the British from the Indians and fall on Tecumseh’s tribesmen.

Harrison forms up his troops in an inverted L, its base facing the British regulars. Shelby is posted at the left end of the base (the angle of the L). Harrison takes a position on the right, facing Procter. The honour of leading the bayonet charge goes to Brigadier-General George Trotter, a thirty-four-year-old veteran. It is a signal choice, for a high proportion of Trotter’s men come from the same Kentucky counties that bore the brunt of the Frenchtown massacre.

An hour and a half passes while Harrison forms his troops. The British, peering through the oaks, the beeches, and the brilliant sugar maples, can catch only glimpses of the enemy, three hundred yards distant. The Americans, waiting to attack, have a better view of the British in their scarlet jackets.

Meanwhile, Richard Johnson has sent Captain Jacob Stucker to examine the shallow swamp through which his troops must gallop in their attack on the Indians. Stucker returns with disappointing news: the swamp is impassable. Finally, the General speaks:

“You must retire, Colonel, and act as a corps of reserve.”

But Johnson has a different idea:

“General Harrison, permit me to charge the enemy and the battle will be won in thirty minutes.” He means the British—not the Indians.

Harrison considers. The redcoats are spread out in open formation with gaps between the clusters of men. The woods are thick with trees, but there is little underbrush. He knows that Johnson has trained his men to ride through the forests of Ohio, firing cartridges to accustom the horses to the sound of gunfire. Most have ridden horseback since childhood; all are expert marksmen.