Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (95 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

On November 6, the flotilla reaches Morristown. Wilkinson is four days later than his most pessimistic promise to Armstrong. Now he must halt, for he fears the British guns at Prescott, a dozen miles downstream. He decides to strip his boats of all armament, march his men along the river bank, hauling the supplies in wagons, and

pass Prescott with the lightly manned boats under cover of darkness. That will cost him another day.

While the boats are being unloaded and the troops formed, he issues a proclamation to the British settlers along the river, urging the farmers to remain at home, promising that the persons and property of non-combatants will be protected.

These sentiments might as well be directed to the wind. This is Loyalist country, and the settlers are already priming their muskets to harass the American flotilla. The river shortly becomes a shooting gallery, with gunfire exploding from the bushes at every twist in the channel.

At noon, Colonel William King, Hampton’s adjutant-general, arrives with the official news of the debacle at Châteauguay. Morgan Lewis takes King downriver to find Wilkinson, who is reconnoitring Prescott. The three men sit on a log as King describes Hampton’s defeat, adding that “our best troops behaved in the most rascally manner.”

“Damn such an army!” Wilkinson cries. “A man might as well be in hell as command it.”

Still, Hampton’s force remains intact—that is some consolation. The two armies number close to eleven thousand men—more than enough, surely, to seize Montreal.

At eight that night the river is shrouded in a heavy fog. Brown, the officer of the day, gives the order to move. Out into the water they go

with muffled oars. The fog lifts, and Brown’s leading gig is subjected to a fearful cannonade. Fifty twenty-four-pound balls are hurled at her from the Canadian shore but with no effect, for the guns are out of range and set too high to do any damage. Brown halts the flotilla, waiting for the moon to set. Its pale light, gleaming on the bayonets of the troops trudging along the shore, has helped identify the manoeuvre to the British, as have signal lights flashing in the homes of certain Ogdensburg citizens friendly to the British cause.

In the midst of all this uproar the irrepressible Winfield Scott arrives. Wilkinson had left him in charge of a skeleton command at Fort George until relieved by the New York State militia. Now, having left his own brigade with the Secretary of War’s permission, he has ridden for thirty hours through the forests of northern New York in a sleet storm. Taken aboard Wilkinson’s passage boat, he is stimulated by the bursting of shells and rockets and the hissing of cannonballs. Scott finds it sublime, though he distrusts and despises his general—an “unprincipled imbecile,” in Scott’s acid view. Years before he was court-martialed for referring publicly to Wilkinson as a liar, a scoundrel, and a traitor. But the ambitious Scott has learned that the road to promotion and power must not be strewn with invective and keeps his feelings to himself. The two men, who have no use for one another, conceal their mutual antipathy behind masks of cordiality.

Wilkinson leaves the passage boat and returns to his gig. Scott, knowing his reputation, is convinced he is drunk, but it is more likely that he is simply intoxicated from repeated draughts of opium, prescribed to ease his dysentery, an ailment that has now spread to most of the older officers, including his second-in-command, Morgan Lewis.

Wilkinson’s condition is so serious that he is finally forced to go ashore and relieve himself at Daniel Thorpe’s farmhouse on the river bank a mile below Ogdensburg. Benjamin Forsyth of the rifle company meets him and helps him up the bank with the aid of another officer. Wilkinson is muttering to himself, hurling imprecations at the British, threatening to blow the enemy’s garrison to dust

and lay waste the entire countryside. The two officers sit him down by the hearth, post a guard at the door to keep the spectacle from prying eyes, and try to decide what to do. By this time Wilkinson is singing bawdy songs and telling obscene stories, to the horror of Thorpe, who also believes him to be drunk. Finally, the General begins to nod and, to the relief of all, allows himself to be put to bed.

November 7 dawns clear and bright, a perfect day for sailing. But the British have reinforced every bend with cannon and sharpshooters. Wilkinson detaches an elite corps of twelve hundred soldiers to clear the bank, with Forsyth’s riflemen detailed as a rearguard. By nightfall the flotilla has moved only eight miles.

Wilkinson is losing his nerve. In his weakened condition he imagines himself in the grip of forces he cannot control. Providence has been fickle, wrecking all his plans for a speedy descent down the river. He has little faith in his own army, especially the contingent from Sackets Harbor. He knows that he has been held up too long, giving Mulcaster every chance to catch him from the rear: the word is that two armed schooners and seven gunboats have already reached Prescott carrying a thousand—perhaps fifteen hundred—men. In his fevered imagination, the General magnifies the forces opposed to him. The farmers on the Canadian shore have been purposely stuffing their interrogators’ heads with wild stories about the dangers ahead—the terrifying rapids, batteries of guns at every narrows, savage Indians prowling the forest, no fodder for the horses. It is said that the army will face five thousand British regulars and twenty thousand Canadian militia—a fantastic overstatement.

On November 8, Wilkinson, who can hardly rise from his bunk, calls a council of war. It agrees, hesitantly, to continue on to Montreal. Still concerned about the forces gathering on the Canadian side, the Major-General orders Jacob Brown to disembark his brigade and take command of the combined forces clearing the north shore.

Ahead lies the dreaded Long Sault, eight miles of white water in which no boats can manoeuvre under enemy fire. Brown’s job is to clear the banks so that the flotilla can navigate these rapids without fear of attack. Harassed now from the rear, Wilkinson

cannot get under way until Brown reaches the head of the rapids. Wilkinson moves eleven miles and, with Mulcaster nipping at his heels, stops again.

The following day, November 10, Mulcaster’s gunboats move in to the attack. At the same time, Brown’s force on the shore runs into heavy resistance. By the time Brown has cleared the bank, the pilots refuse to take the boats through the white water. The flotilla moves two miles past John Crysler’s farm to Cook’s Point, a mile or two above the Long Sault. The troops on shore build fires from the farmers’ rail fences and shiver out the night in the rain and sleet. Jarvis Hanks, the drummer boy in the 11th, pulls a leather cap over his head and curls up so close to the fire that by morning both his cap and his shoes are charred. Brown, meanwhile, has gone aboard Wilkinson’s passage boat to find out exactly who is in charge. But Wilkinson is too sick to see him. It has taken eight days for the fleet to move eighty miles. A log drifting down the river could make the same distance in two.

JOHN CRYSLER’S FARM, ST. LAWRENCE RIVER, UPPER CANADA, NOVEMBER 11, 1813

Dawn breaks, bleak and soggy. John Loucks, one of three troopers in the Provincial Dragoons posted with three companies of Canadian Voltigeurs and a few Indians a mile ahead of the main British force, spots a movement through the trees ahead. A party of Americans is advancing from Cook’s Point, where Wilkinson’s flotilla is anchored. A musket explodes from the woods on his left, where a party of Indians is stationed. The Americans reply with a volley that kicks the sand in front of the troopers’ horses. Off goes young Loucks at a gallop, heading for the headquarters of the British commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Wanton Morrison.

As the three dragoons dash through the ranks of the 49th Regiment, Lieutenant John Sewell is in the act of toasting a piece of breakfast pork on the point of his sword. He needs hot nourishment, for he has slept on the cold ground all night, his firelock

between his legs to protect it from the icy rain, laced with sleet. Now it seems, there will be no time for breakfast, as his company commander shouts to him:

“Jack, drop cooking, the enemy is advancing.”

The British troops are scrambling into position behind a stout rail fence, but the warning is several hours premature. All that Loucks has encountered is an American reconnaissance party. A regular officer chides him gently for his precipitate gallop: it is perfectly all right to fall back, he explains, but it is bad form to ride so fast in the face of the enemy.

At his headquarters in the Crysler farmhouse, hard by the King’s Highway that runs along the river bank, Colonel Morrison assesses his position. He has been chasing Wilkinson in Mulcaster’s gunboats for five days, ever since word reached Kingston that the main American attack would be on Montreal. Now he has caught up with him. Will the Americans stand and fight or will the chase continue? With a force of only eight hundred men to challenge Wilkinson’s seven thousand, Morrison is not eager for a pitched battle. But if he must have one, it will be on ground of his choosing—a European-style battle here on an open plain where his regulars can manoeuvre, as on a parade ground, standing shoulder to shoulder in two parallel lines, each man occupying twenty-two inches of space, advancing with the bayonet, wheeling effortlessly when ordered, or moving into echelon—a staggered series of platoons, each supporting its neighbour.

This is the kind of warfare for which his two regiments have been trained: Brock’s old regiment, the 49th, known as the Green Tigers both from the facings on their lapels and for the fierceness of their attack; and his own regiment, the 89th. The Green Tigers have had their fill of fighting, from Queenston to Stoney Creek, but the 89th are new to North America. Morrison, their commanding officer and senior commander on the field, has just turned fifty. Like his father before him, he has served half his life in the British Army, shifted from continent to continent wherever his country needs him, from Holland, where he was wounded, to the Caribbean, to Canada. He has never handled a battalion in battle; but he has been singled out as an attentive and zealous officer, and he has solid support in John Harvey, his second-in-command, and Charles Plenderleath of the 49th, both veterans of Stoney Creek.

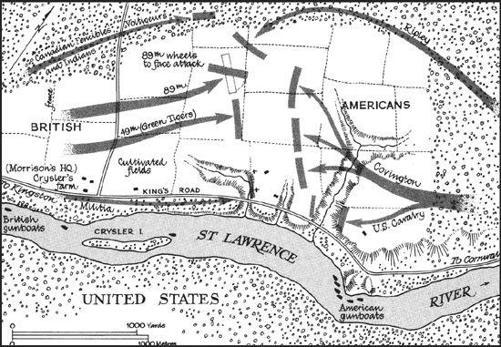

The Battle of Crysler’s Farm: Phase 1

He has chosen his position carefully, anchoring his thin line between the river on his right (where Mulcaster’s gunboats will give support) and an impenetrable black ash swamp about half a mile to his left. His men are protected by a heavy fence of cedar logs, five feet high. Ahead for a half-mile stretches a muddy field covered with winter wheat, cut with gullies and bisected by a stream that trickles out of the swamp to become a deep ravine running into the St. Lawrence.

Behind the fence, the 49th occupies the right, close to the river and to the King’s Highway that runs along the bank. The 89th is on the left, nearer the swamp; its soldiers wear scarlet coats, but the battle-seasoned 49th hide their distinctive tunics with grey overcoats.

Half a mile forward of this main body are lighter troops, including Canadian Fencibles. Another half-mile farther on are the

skirmishers—Indians and Voltigeurs, the latter almost invisible in their grey homespun, concealed behind rocks, stumps, and fences.

Though heavily outnumbered, Morrison is counting on the ability of the British regulars to hold fast against the more individualistic Americans. Here the contrast between the two countries, so recently separated and estranged, becomes apparent. Wilkinson’s men are experienced bush fighters, brought up with firearms, blooded in frontier Indian wars, used to taking individual action in skirmishes where every man must act on his own if he is to escape with a whole skin. But the British soldier is drilled to stand unflinching with his comrades in the face of exploding cannon, to hold his fire until ordered so that the maximum effect of the spraying muskets can be felt, to move in machine-like unison with hundreds of others, each man an automaton. The British regular follows orders implicitly; the American volunteer is less subservient, sometimes to the point of anarchy. This British emphasis on “order” extends, in Canada, to government. If the Canadians accept a form of benevolent dictatorship, or at least autocracy, it is because they have opted for a lifestyle different from that of their neighbours, a lifestyle based on British attitudes and institutions. Under the impetus of war, that attitude is hardening.

Morrison has one advantage of which he is unaware. The American high command is prostrate. In separate boats anchored at Cook’s Point, the chief of the invading army and his second-in-command both lie deathly ill, unable to direct any battle. Lewis, confined to a closet-like cabin and dosing himself on blackberry jelly, is even less capable than his enfeebled superior. Wilkinson, unable to rise from his bunk, awaits word from Jacob Brown on shore that the rapids ahead have been cleared of British troops. At 10:30 a dragoon arrives with the expected reassurance. The Commander-in-Chief is in a quandary. Mulcaster is directly astern. What if the British gunboats should slip past him? He gives a tentative order to the flotilla to get under way and orders Brigadier-General Boyd, on land, to begin marching his men toward Cornwall. Even as he does so he is alerted to the presence of British redcoats on Crysler’s field. At the

same time Mulcaster begins to lob shot in his direction. Wilkinson decides to destroy the small British force before moving on.