Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (117 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

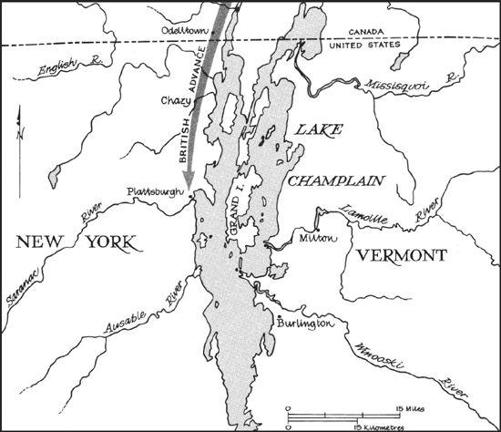

With thousands of Wellington’s veterans shipped across the Atlantic to reinforce his thin army, Sir George Prevost can at last go on the offensive. He intends to march his troops—eleven thousand strong—down the Richelieu-Champlain corridor and take the war into New York State. To succeed he must seize Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain and destroy the newly built American fleet anchored in Plattsburgh Bay. All year, the two opposing navies on the lake have been engaged in a shipbuilding contest. As the British flotilla nears completion and Prevost’s army marches south, the American commodore, Thomas Macdonough, awaits the coming attack

.

ABOARD U.S.

SARATOGA

, PLATTSBURGH BAY, NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 4, 1814

Sunday dinner aboard the flagship of Commodore Thomas Macdonough, commander of the American fleet on Lake Champlain. The Commodore’s gig arrives bringing a guest, a Yale student, John

H. Dulles of Philadelphia. As the sun approaches the meridian, a pre-dinner service is held on deck, and young Dulles notes that the three hundred members of the naval congregation are more than usually devout. He remarks on this to the Commodore, who replies, drily, “You must not be deceived by an inference that it is from pious feelings altogether.” He smiles and adds, “There are other considerations controlling their conduct.” There are indeed. Thomas Macdonough is totally in control of his fleet. Dulles, chatting with some junior officers, is “struck with the palpable evidence of the one pervading spirit of a master mind.”

In spite of the stalemate on the Niagara peninsula, the war is far from over. On this Sunday afternoon, as Gordon Drummond continues to lob cannonballs at Fort Erie and the five Americans at Ghent begin, at last, to fence with their British counterparts, Sir George Prevost’s vast army is marching down the western shore of Lake Champlain, virtually unopposed. A few miles to the north,

a new British fleet is nearing completion. But here on Thomas Macdonough’s flagship, all is calm.

Lake Champlain, 1814

In his cabin, Macdonough quietly discusses the possibilities of the coming action. If the British destroy his fleet, he explains, Sir George Prevost can march his army, unobstructed, to the capital at Albany—even on to New York City, there to dictate an ignominious peace. The next few days will be decisive.

Dulles is impressed by Macdonough, who speaks “with the singular simplicity and with the dignity of a Christian gentleman.” The Commodore looks younger than his thirty-one years. He has a light, agile frame and a bony face—all nose and jaw. His faith in a living God is unbounded. To Dulles he quotes from the epistle of St. James with its naval illustrations:

“He that wavereth is like a wave of the sea driven with the wind,” and “Behold the ships, though so great, are turned about with a very small helm.”

The chaplain offers a blessing before the midday meal. Halfway through a message arrives, which the Commodore relays to his officers:

“Gentlemen … I am just informed by the commander of the army that the signs of advance by the British forces will be signalled by two guns, and you will act accordingly.”

He leaves the table and the conversation livens. One of the juniors makes so bold as to illustrate a remark with an oath, whereupon another turns to him and declares:

“Sir, I am astonished at your using such language. You know you would not do it if the Commodore was present.”

Dead silence as the rebuke sinks in. What a curious company is this! Hardly the blasphemous and salty fraternity of song and story.

But then, no one would describe Thomas Macdonough as salty, though he has spent half his life in the navy. He is a devout Episcopalian, his religion so much a part of him that it cannot be separated from the rest of his personality. He does not flaunt his faith, for he has learned in fifteen years of naval service to keep himself under tight control, to curb a tendency toward impetuosity—even

rashness. He is known as an amiable, even placid officer, not one to betray emotion.

And he is a survivor. One of Stephen Decatur’s favourite midshipmen, he saw active service in the Mediterranean. He is brave and he is tough. Once, in hand-to-hand fighting on a Tripolitan gunboat when his cutlass broke, Macdonough wrested a pistol from his nearest assailant and shot him dead. Later he survived an epidemic of yellow fever that killed all but three of his shipmates. Two years of service on Lake Champlain, however, have worn him down, leaving him prey to the tuberculosis that will eventually kill him.

As on Erie and Ontario, the British and Americans on Lake Champlain have been engaged in a shipbuilding race. It has not been easy for Macdonough, who has had to compete with Chauncey for men and supplies. Yet, with the help of Noah Brown, the New York shipbuilding genius who worked on Perry’s fleet, he has outdone Perry. In the spring, Brown launched the twenty-six-gun

Saratoga

, larger than any of Erie’s vessels. Then, when Macdonough discovered that the British were building an even larger vessel,

Confiance

, he undertook to construct a second, the twenty-gun

Eagle

, launched in a record seventeen days after the keel was laid. Now he has outstripped the British, for

Eagle

has joined his squadron while the British flagship has yet to be rigged.

The creation of Macdonough’s fleet has been a masterpiece of organization and ingenuity. One vessel, the seventeen-gun

Ticonderoga

, is a former steamer, transformed by Brown into a schooner. Guns, cannon, shot, cables, and cordage have been hauled hundreds of miles to the shipyards at Otter Creek. Here, in the saw pits, green timber has been turned into planking while local blacksmiths have hammered out nails, bolts, fastenings, wire. Besides his two large vessels and

Ticonderoga

, Macdonough has three smaller sloops, six two-gun galleys, each manned by forty oarsmen, and four smaller galleys—sixteen vessels in all.

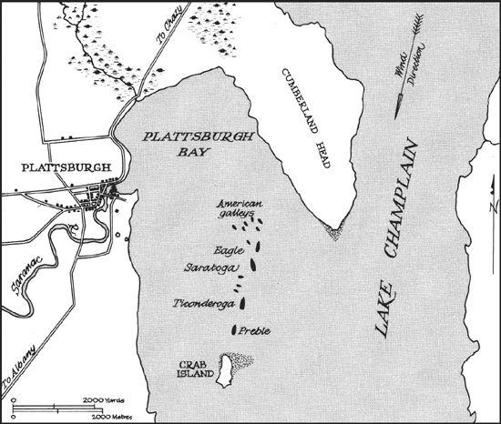

Now, with Prevost’s army sweeping everything before it, Macdonough waits for the British fleet. He knows he cannot beat it in the open water, where the British long guns can savage his vessels at a comfortable distance. He must force them to come to him—to do battle within the confines of Plattsburgh Bay, where his powerful short-range carronades may hammer them to matchwood.

Will Downie, the British commander, hold his fleet outside the bay? Macdonough thinks not: at this season the possibility of a destructive gale is too great. But once they enter the bay, Macdonough can fight at a site of his own choosing.

The long narrow lake runs north and south, with the prevailing winds blowing from the north. Macdonough expects the British fleet will sweep up the lake toward its objective with the north wind behind it. Once the ships round Cumberland Head, however, they must turn into the wind in order to manoeuvre into the bay. They may, of course, drive directly across the mouth of the bay, but that is unlikely, for it would place them within range of the shore batteries on the far side.

With this in mind, Macdonough carefully places his fleet in a chain across the bay, stretching from the shallows near Crab Island on his right to Cumberland Head on his left. The chain runs almost north and south; that will force the British to attack bows on, a position that will allow Macdonough to rake their vessels from bow to stern. Nor can the British stand off out of range and batter the Americans with their long guns. Macdonough has so chosen his position in the cramped bay that there is not enough room.

He intends to fight at anchor, forcing the British to come to him, his vessels little more than floating batteries. It can be dangerous. He must be aware that Nelson destroyed two fleets at anchor—the French on the Nile, the Danes at Copenhagen. But Nelson had the wind behind him. By hitting the enemy line on the windward he was able to bear down on the opposing fleet and roll it up, ship by ship. Downie, the British commodore, cannot duplicate Nelson’s feat from the leeward; the geography of Plattsburgh Bay makes that impossible. It is hard enough with lake vessels of shallow drafts and flat bottoms to beat up, close-hauled, against the wind.

Macdonough plans one further precaution. He must be able to manoeuvre quickly at anchor, without putting on sail. To do that, he equips his flagship,

Saratoga

, with a series of anchors and cables

that will allow him to twist it about in any direction—through an arc of 180 degrees if necessary—in order to bring his guns to bear on targets of opportunity.

Macdonough at Anchor, Plattsburgh Bay, September, 1814

He cannot know what the British will do. He can only make an educated guess, based on his knowledge of the winds, the geography of the lake, his own capabilities, and the enemy’s objectives.

The British are determined to seize Plattsburgh and destroy its defenders. To accomplish that and to continue on through the state, they must have naval support. That they cannot have without a naval victory. For once, the approaching winter is to the Americans’ advantage. With the season far advanced, Macdonough is betting that Prevost will not hazard a blockade but will opt immediately for a combined attack by Downie’s squadron and his formidable army. If he does, and if the God in whom the Commodore so devoutly believes gives him favourable winds, Macdonough is calmly confident of victory.

PLATTSBURGH, NEW YORK, SEPTEMBER 7, 1814

Sir George Prevost’s mighty army—the greatest yet assembled on the border—pours into Plattsburgh’s outskirts in two dense columns, brushing aside the weak American defenders like ineffectual insects.

These are Wellington’s veterans. With Napoleon confined to Elba and the conflict in Europe at an end, sixteen thousand were brought across the Atlantic to finish the war in North America. Prevost has at least eleven thousand on this march through upper New York State. The logistics are awesome. To maintain its new army in Canada, Britain must ship daily supplies weighing forty-five tons across the ocean—a drain upon the British treasury which English property owners, facing new taxes, are beginning to deplore.

At eight in the morning, Major John E. Wool attempts to stem the scarlet tide. He has no chance. The heavy British column presses forward at a steady 108 paces to the minute, completely filling the roadway and routing the militia. An artillery captain tries to support Wool. His cannonballs tear heavy lanes through the British ranks, but the disciplined veterans march inexorably on, filling the gaps as they go. They disdain to deploy into line. Instead, as the bugles sound, the flanking companies toss aside their knapsacks, rush forward at a smart double, and disperse the fleeing Americans at bayonet point even as the main body marches on.

Prevost’s brigades are under the direct control of Major-General De Rottenburg, who commands three battle-wise major-generals from Wellington’s army—Manley Power, Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, and Frederick Philipse Robinson. They have been hand picked by the Iron Duke himself; he considers them the best he has. Not surprisingly, all three are sceptical of the colonial high command. Neither Prevost, De Rottenburg, nor the Adjutant-General, Colonel Baynes, now promoted to major-general, have much battle experience.

As the troops march into Plattsburgh against light resistance, Robinson has further cause to question Prevost’s capabilities. He has already realized that the army is moving on its objective without

any carefully thought-out plan. Now, as he approaches the Saranac River, the major obstacle between the American redoubts and the advancing British, his doubts are confirmed.

Prevost proposes an immediate attack. Is Robinson prepared to launch his demi-brigade in an assault on the heights across the river?

Robinson is always ready, but he has some questions:

Is the river fordable and, if so, where? What is the ground like on the other side? How far will the men have to march to reach the American redoubts? Are experienced guides available?

To his dismay, he is told that no one has the answers to any of these queries.