Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (113 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Drummond and his opposite number, Brigadier-General Edmund Pendleton Gaines (Ripley’s replacement) are like blind men, groping

to test each other’s strength. Both have miscalculated. Because the British entrenchments are hidden behind a screen of trees, Gaines can only guess at Drummond’s force, which he estimates at five thousand. Actually, Drummond has fewer than three thousand men. Drummond is misled by his spies and informers into believing the Americans have fifteen hundred troops. In fact, Gaines has almost twice that number. Drummond has made another error: the explosion of the magazine has produced few casualties. And Gaines, shrewdly reading his opponent’s mind, is now expecting an immediate attack.

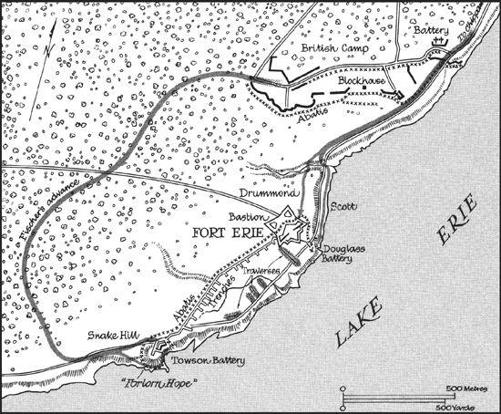

Drummond plans a simultaneous assault on each of the three major gun batteries that protect the corners of the fifteen-acre encampment. The camp is surrounded on three sides by embankments, ditches, and palisades. Directly ahead, at the near corner, not more than five hundred yards from the forward British lines, the Lieutenant-General can see the outlines of the old fort, now bristling with cannon. One hundred and fifty yards to the left, on the edge of the lake, is a second artillery battery commanded by David Douglass. The two are connected by a vast wall of earth, seven feet high, eighteen feet thick. Half a mile up the lake, and also connected to the fort by an enclosed rampart, is Nathan Towson’s battery of five guns, perched on a conical mound of sand, thirty feet high, known as Snake Hill and joined to the lake by a double ditch and abatis. If Drummond’s plan succeeds, his assault forces will strike all three batteries at the same time and seize the encampment.

At 4

P.M

. his main force sets off. Its task is to attack Towson’s battery on Snake Hill. Drummond orders it to march down the Garrison Road, screened from view by the forest, to rendezvous on the far side of the American encampment, and to attack at two the following morning. The General orders the troops to remove the flints from their firelocks and to depend entirely upon the bayonet, identifying the enemy in the dark by their white pantaloons. Loud talking is prohibited and the roll is to be called every hour to frustrate desertions.

This last is a curious instruction. Does Gordon Drummond actually expect a body of his men to steal away in the dark of the night?

Clearly he does. The bulk of the thousand-man force attacking the Towson battery is made up of soldiers from the de Watteville regiment, a foreign corps recruited twenty years before in Switzerland but shattered during the Peninsular campaign and now heavily interlaced with prisoners of war and deserters from Napoleon’s armies—French, German, Dutch, Italian, Polish, and Portuguese. Their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Fischer, is an able officer; he has under his command a smattering of British regulars from the King’s and the 89th. They may stiffen the backs of the less-disciplined de Wattevilles, but the motley foreign corps forms the majority.

The Siege of Fort Erie

Drummond considers the attack on Snake Hill to be the key to success. If Fischer and his men can capture that end of the encampment, victory is certain. But why has he committed his poorest troops to this critical night attack? In his eagerness to rid the peninsula of the invading army, Drummond is acting precipitately. He

has not bothered to reconnoitre the defences at Snake Hill, where a vast abatis of tangled roots and branches can inhibit any assault force. Nor does he plan to soften those defences with cannon fire—he has purposely refrained from bombarding the position in order to conceal his real purpose from Gaines. Secure in his overconfident conviction that the Americans are outnumbered and demoralized, he plunges ahead in the belief that he can conquer by surprise alone.

He has divided his force. While Fischer assaults the far end of the camp, two smaller detachments will attack the near end. The General’s nephew, Lieutenant-Colonel William Drummond of Keltie, will lead 360 men against the ramparts of the original fort. Lieutenant-Colonel Hercules Scott will lead another seven hundred against the Douglass battery on the lakeshore and against the embankment that connects it to the old fort. Scott’s regiment is the notorious 103rd, originally the New South Wales Fencibles, known in that colony as “the rum regiment,” brought up to strength before sailing for Canada by the recruitment of released convicts. Two of its companies are composed of boys below fighting age.

Two more antithetic characters than Hercules Scott and William Drummond could scarcely be found in a single army corps. Scott is a bitter man who despises his commanding officer. He does not believe that the assault on the American encampment has any hope of success. But he is a courageous officer and can be expected to do his duty. He sleeps that night in the drenching rain under a piece of canvas suspended from a tree and jauntily tells his surgeon, “We shall breakfast in the fort in the morning.” Privately he is less optimistic; he has already written out a brief will and mailed it to his brother, for he is half convinced that he will not return from the attack.

Only in this respect does he resemble the General’s nephew. Every army knows at least one field officer like William Drummond—colourful, dashing, eccentric, ruthless—the sort of leader that men will follow into the mouths of cannon. Such men rarely rise above field rank, for they are either killed in action or barred from promotion by their own quirkiness. There does not seem to be a nerve in Drummond’s body. Perhaps he lacks the imagination to be afraid.

He is a fatalist who spends the day in high spirits, spinning yarns with a wide circle of cronies, then as the bugles sound turns solemnly to his friends, and remarks:

“Now, boys! We never will all meet together here again; at least I will never again meet you, I feel it and am certain of it.”

A thick rain is falling; soon it becomes a torrent. The General’s nephew leaves the leaky hut in which the others are smoking and talking, finds a rocket case, stows himself away in it, and is soon fast asleep as if this were not his last day on earth.

Beyond the American camp, the same downpour soaks Fischer’s mixed bag of British regulars and foreign mercenaries as they move through the forest.

It is two in the morning. In a clump of dripping oaks, three hundred yards in front of Snake Hill, a picket of one hundred Americans hears the steady

swish-swish

of the approaching column and sounds the alarm. Surprise, the essence of Drummond’s plan, has not been achieved.

Towson’s artillery is already in action. The British attackers are illuminated in a sheet of flame, a pyrotechnical display so bright that Snake Hill will shortly be dubbed Towson’s Lighthouse.

Now Fischer comes up against the formidable abatis that the Americans have constructed between Snake Hill and the lake—thousands of tree trunks, four to six inches in diameter, their branches cut off three feet above the base, pointing in all directions and forming an impassable tangle. Unable to breach this labyrinth and the embankment behind it, Fischer’s Forlorn Hope dashes around the end on the American left and into the lake in the hope of taking the defenders from the rear. The current is swift, the channel a maze of slippery rocks. The men struggle in waist-deep water. Part of the Forlorn Hope does reach the rear of the battery to fight hand to hand with the defenders, but two companies of Eleazer Wood’s 21st, especially detailed for such an emergency, pour a galling fire on those who follow.

Panic seizes the men of the de Watteville regiment struggling in the water. Some, dead or badly wounded, are being borne into

the Niagara River by the stiff current. Shouting wildly, they break in confusion, turn tail, and plunge directly into the King’s, carrying those veterans with them like a torrent. Only the seasoned 89th holds fast. The hundred men of the Forlorn Hope who have managed to penetrate the American defences are killed or captured.

Fischer, meanwhile, is attempting to storm the Towson battery with the rest of his force, only to find that his scaling ladders are too short to reach the parapet. Worse, he cannot reply to the heavy fire being poured down on him because, to ensure secrecy, his men have been ordered to remove the flints from their muskets. He charges the parapet five times before giving up. His losses are heavy. Many of the de Watteville regiment have deserted and are hiding in the woods. The King’s, too, have been badly mauled during the panic. Only the 89th, which maintained its order, is intact.

Drummond’s principal attack has failed. Success now depends entirely on the forces of his flamboyant nephew and those of the embittered Hercules Scott.

At the other end of the American camp, David Bates Douglass has kept his men on the

qui vive

, warned by his commander, Brigadier-General Gaines, that a British attack is certain. Midnight passes without incident; then two o’clock. Nothing. Stretched out on his camp bed, Douglass begins to doubt that the assault will come. Slowly, the tension that has been keeping sleep away subsides and he slips into slumber.

Still asleep, he hears—what? A musket shot? Or is it part of his dream? Another volley follows. His body responds before his brain; he is on his feet before he is awake. In the distance, on the far left, comes another volley. This is no dream!

The cry “To arms! To arms!” ripples along his line of tents. The reserve is aroused and formed in the space of sixty seconds. On Douglass’s left, the American 9th battalion, bayonets fixed, has already formed a double line. His own corps is wide awake and

standing to their guns, the primers holding their hands over the priming to protect it from dampness, the firemen opening their dark lanterns, lighting their slow matches.

Up the river, at Snake Hill, the sky is brilliantly lit with rocket flares, bomb bursts, and musket fire. The sound of small arms and artillery, blended together, becomes a continuous roar like a stupendous drum roll.

Douglass has seen the signal rockets rise from the woods in front of him in answer to those from Fischer’s column, but there is yet no hint of an attack on his battery. As the minutes tick by, tension starts to build.

“Why don’t the lazy rascals make haste?” someone whispers.

It is another axiom of war that the more complex the plan the more unlikely it is of success. Drummond’s three attacks were supposed to take place simultaneously—difficult enough in broad daylight, let alone pitch darkness. Hercules Scott’s men should have assaulted Douglass’s position the instant Fischer’s rockets went up, but his battalion is still moving along the lakeshore, just below the embankment, as yet unseen but certainly heard. The tramp of seven hundred pairs of feet on the soft sand and the low whispers of the officers keeping their men together carries clearly through the night air:

“Close up … Steady! … Steady men, steady … Steel … Captain Steel’s company.”

The sound of plodding feet grows louder. Then, as if on a signal, a sheet of fire blazes, and the batteries along the entrenchment from the water to the fort open up in reply.

It is three o’clock. Douglass is firing his cannon at point-blank range, cramming each to the muzzle with round shot, canister, and bags of musket balls—stuffing each barrel so full that he can touch the last piece of wadding with his hand.

From the direction of the old fort comes a sudden cry:

“Cease firing! You are firing on your own men!”

As Douglass considers, the fire slackens momentarily. But the voice was stiffly British; this, he guesses is a

ruse de guerre

. A second voice calls out in an American twang:

“Go to hell. Fire away, there, why don’t you?” and the cannonade continues.

Hercules Scott’s column surges forward with scaling ladders, seeking to surmount the breastwork. Again and again the British are repulsed. Of twenty officers, only four escape without wounds. More than half the regiment are casualties. By dawn it is clear that the attempt has failed.

On Scott’s right, Drummond of Keltie is more successful. He forms up his men in a deep ravine, unbuckles his sword, and asks his friend Dunlop, the surgeon, to keep it for him; he prefers a boarding pike and pistol. Then he leads his 350 men in a dash across the open plain to the fort.