Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (115 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Lieutenant George Gleig, an eighteen-year-old subaltern in the British 85th, clambers off a landing launch, loaded down with equipment, sweltering in his thick wool uniform, feeling the effects of ten weeks on shipboard. Since leaving France at the end of May he has been almost constantly cooped up in a tiny stateroom with forty

fellow officers, without exercise, subject to seasickness, threatened with typhoid—not the best preparation for a long march in the August heat with the prospect of a battle at the end.

The villagers have deserted Benedict, but now the empty streets come alive as forty-five hundred British soldiers—Wellington’s Invincibles—pile out of the boats and sort themselves into three brigades. Some begin to forage for extra food. Gleig finds three ducks, and the following morning he and his friend Lieutenant Codd manage to buy a pig, a goose, and a couple of chickens from a solitary farm wife. But before they can enjoy their feast, the bugle sounds assembly.

As the three brigades march off toward Washington, their commander, Major-General Robert Ross, a blue-eyed Irishman of forty-seven, one of Wellington’s best officers, rides past to the cheers of his men. Ross has some doubts about this venture. His troops, languishing aboard ship, are badly out of shape. He has no cavalry and only three small field guns. The terrain ahead, cut by streams and bordered by forests, can be easily defended. He has been persuaded, however, by his naval colleague, Rear-Admiral George Cockburn, that a two-pronged attack up Chesapeake Bay is practical—with the fleet seizing the American flotilla of gunboats and the army marching on the capital by a parallel route.

Ross is new to North America, but Cockburn has been skirmishing off the coast for more than a year and knows every inlet in the long, narrow bay. At forty-two he is a seasoned commander, famous for his lightning thrusts at American seaboard settlements. In an earlier decade he might have been a buccaneer. The plan to seize and burn Washington is his.

Ross’s column manages only six miles. The march is a horror, the men groaning under their heavy baggage, choking with dust, half dead from heat and fatigue. Scores fall exhausted by the wayside. George Gleig has never felt so tired, though he remembers that during the Peninsular campaign he often marched thrice this distance without difficulty.

Surprisingly, the British advance is unimpeded. No one has blocked the road or burned any bridges. Except for a few shots fired from the

woods there is no harassment on the flanks, no attempt at ambush. The real enemy is the weather. In August, Maryland is a furnace.

Still, General Ross has misgivings. Admiral Cockburn, having chased the Americans into a cul-de-sac and forced them to blow up their gunboats, arrives on horseback to stiffen his colleague’s resolve. The high command is also nervous. At two in the morning of August 24, both commanders are awakened by a courier from their commander-in-chief, Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, who orders them to return at once.

A whispered argument follows between Ross and Cockburn as Ross’s aides strain to listen. Clearly Cockburn wants to go on, in spite of orders. They hear the phrase “stain upon our arms.” They hear him pledge success. They see Ross waver and finally, as dawn breaks, see him strike his head and say: “Well, be it so, we will proceed.”

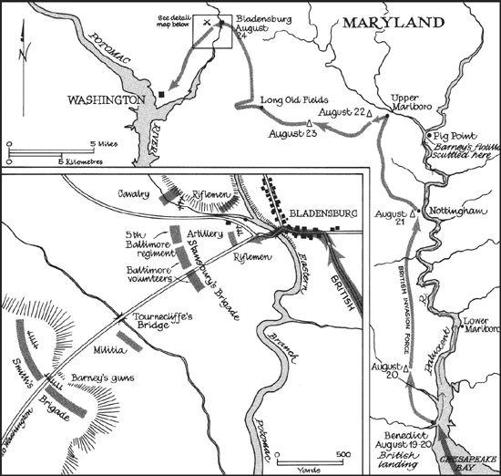

George Gleig has spent a sleepless night on picket duty, two miles ahead of the main British force, with only sixteen men, fearing imminent capture. He has no time to rest, for when he returns to camp at five, the army is ready to march. He can hardly drag one foot ahead of the other, but he knows that Washington is only a few miles ahead, across the Potomac. Just past the community of Long Old Fields the road forks, one route leading directly to the capital, the other circling around to the right, a longer distance through the village of Bladensburg. Ross leads his weary men onto the direct fork, then suddenly reverses his column and opts for the Bladensburg road. His plan is to throw the Americans off guard; they will not have been expecting this. Nor have his men. By the time they reach the village in the scorching sun, they have marched fourteen miles and some are lying dead from exhaustion by the wayside.

It is noon as the troops trudge into the village. They have already seen huge clouds of dust in the distance and realize that the Americans are marching to meet them. But Bladensburg is empty of the enemy; the Americans have not fortified it, an error that causes relief. Few have the stomach for street fighting.

On the heights above the village, directly ahead and beyond the single bridge that crosses the Potomac’s shallow eastern branch—surprisingly

still intact—George Gleig in the light brigade can see the enemy drawn up in line. Few are in uniform, some in blue, some in black, many in hunting jackets or frock coats. To Gleig they look like “country people,” in stark contrast to the disciplined British regulars.

The British March on Washington, August 19–24, 1814

Gleig’s brigade commander, Colonel William Thornton, thinks so, too. He does not want to wait for the rest of the army: the American militia, he insists, cannot stand a determined bayonet charge, supported by rocket fire. When Harry Smith, the General’s aide, urges caution, Thornton becomes furious, and when Ross supports him, Smith is flabbergasted.

“General,” he says, “neither of the other brigades will be up in time to support this mad attack and if the enemy fight, Thornton’s brigade must be repulsed.”

But Ross has made up his mind.

“If it rain militia,” says the General, “we will go on.”

Off goes Thornton on his grey horse, sword flashing in the sun, leading his brigade through the streets. As he reaches the river, the American guns open up. A moment before, George Gleig had felt he could not move another step; now, as the Battle of Bladensburg begins, he finds himself sprinting toward the bridge like a young colt.

WASHINGTON, D.C., AUGUST 24, 1814

Brigadier-General William Winder, the Baltimore lawyer placed in charge of the defence of Washington, worries and frets. For five days, without much sleep, he has been trying frantically to raise a force of militia to oppose the British, whose intentions he does not know and cannot guess. For most of the night he has been stumbling about on foot, his horse played out, his right arm and ankle in pain from a fall in a ditch. His own subordinates cannot find him and, for a time, believe him a captive of the British.

Now, having inspected the forces guarding the bridge over the east branch of the Potomac—the entrance to the city—he snatches an hour’s sleep on a camp cot. If the British do intend to attack Washington, he reasons, they will probably come this way by the direct route from Long Old Fields. On the other hand, they may have another objective—Annapolis, perhaps, or Fort Warburton. He cannot tell. It is also possible they may take a more roundabout route to the capital, through Bladensburg. What to do? If he goes to Bladensburg, he leaves the other route wide open.

Few believe the British intend to attack Washington. The Secretary of War is one doubter. “They certainly will not come here,” John Armstrong has declared. “What the devil will they do here? No! No! Baltimore is the place … that is of so much more consequence.” This incredulity helps explain why so few have answered the call to arms.

Winder’s military career has not been glorious. Captured by the British as he blundered about in the dark at Stoney Creek and exchanged a year later, he holds his present post partly because he is

available and partly because he is a nephew of Maryland’s governor, whose state has not been the most enthusiastic supporter of the war. That blood relationship, however, has not paid off. Of six thousand Marylanders called out by federal draft on July 4, only 250 were under Winder’s command the day the British landed. The Pennsylvania record is even worse. That state was supposed to supply five thousand men but has sent none because its militia law has expired, and no one has yet got around to renewing it.

Winder should have fifteen thousand men—the number called for by the government. Two days before he could count only three thousand. Now, with the redcoats only eight miles away, more troops are trickling in. None are trained because the government would not call on them until the danger was “imminent.” And some will not see action because of a maddening bureaucracy. As Winder fidgets and waits for word of the British line of march, seven hundred frustrated arrivals from Virginia are vainly attempting to get arms from the War Department. The clerk in charge arrives at last and begins doling out flints, one at a time, counting each carefully. When an officer tries to speed things up, he starts the count over again. These men will not see action today.

Because he cannot be sure of the British intentions, Winder has had to divide his forces. Two thousand Marylanders under Brigadier-General Tobias Stansbury occupy Bladensburg. Some arrived only the previous night and have hardly had time to settle in. Another six hundred are on their way from Annapolis; Winder does not know where they are. At the Potomac bridge on the eastern outskirts of Washington, ready to march in either of two directions, he has fifteen hundred District of Columbia militia under Brigadier-General Walter Smith. In addition, there are a handful of regulars, a couple of hundred dragoons, and four hundred naval men, anxious to get into action now that the flotilla has been destroyed.

The sun is scarcely up before Winder receives mortifying news from General Stansbury at Bladensburg. Fearing the British may take another route and cut him off, he has moved his exhausted Marylanders out of the village and back toward Washington. Winder

orders him forward again. Stansbury’s troops, who have been up most of the night, return as far as the heights above Bladensburg, commanding the bridge across the river, but do not occupy the village.

At ten, Winder’s scouts gallop in and the General finally learns the British intentions: they have taken the longer route through Bladensburg. That is where he must oppose them. He moves to combine his forces, orders General Smith to march his brigade off immediately to join Stansbury. An hour later he follows as does most of the Cabinet, including the President. James Monroe, the Secretary of State, a onetime colonel in the Revolutionary army, dashes on ahead. It has always been his ambition to be commander-in-chief of the American forces in this war; now he has a chance to display his military acumen.

On the heights above the village, John Pendleton Kennedy of the crack United Company of the 5th Baltimore Light Dragoons—the “Baltimore 5th,” as they are known—can hardly keep himself awake. He has actually had the novel experience of sleeping while on the march. What began as a glittering adventure—banners flying, bands playing, the populace huzzahing at every corner—has taken a darker turn. His comrades belong to the elite of Baltimore—barristers, professionals, wealthy merchants; he and his five friends have even brought along a black servant, Lige, to wait on them. But now the picnic is over. Routed out in the dark only hours after arriving, their kits in disarray, marched and countermarched in the night, they are used up. Kennedy has lost his boots in the midnight scramble to retire and is wearing dancing pumps on his swollen feet.

The British are only three miles away, but now another mix-up bedevils the Baltimore 5th. Having taken their position on the left of the forward line, supporting the riflemen and artillery, they are suddenly ordered back a quarter of a mile to an exposed position which leaves the forward guns and rifles without support. This is the work of Monroe, the Secretary of State, who has butted in, uninvited and without the knowledge of General Stansbury. By the time Winder arrives to inspect the lines, it is too late to make any change.

Stansbury’s force is deployed in two ragged lines: the sharpshooters

(most of whom have only muskets, not rifles) and cannons well forward, the three Maryland regiments some distance behind with the crack 5th on the left, its field of fire impeded by an orchard. These will bear the brunt of the British attack. A mile to the rear, another line is hastily forming as the troops arrive—Smith’s brigade from Washington and several hundred footsore militia from Annapolis, who have already marched sixteen miles. None, save a few regulars and the naval detachment, have had any recent training because, as the Secretary of War has told Winder, the best way to use the militia is on the spur of the occasion—to bring them to fight as soon as called out.

The Secretary of War is the last of the Cabinet to arrive on the heights above Bladensburg. The President is already here, a small, frail figure in black, two borrowed duelling pistols at his waist. He stands behind Stansbury’s lines with the Attorney General and the Secretaries of State, War, and Treasury. This is a motley crew, their personal relations fraught with jealousies, hatreds, ambitions. Armstrong has no use for Winder, who was not his choice for commander-in-chief; he has pointedly ignored the General’s letters pleading for reinforcements. Monroe and Madison have little liking for Armstrong, whom they see as a possible political rival. Armstrong for once has nothing to say; having made no effort to defend the capital, he must realize that his days in office are numbered.