Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (110 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Brown is aware that as each day passes the British forces grow stronger. The frontier is in a ferment. Guerrilla warfare rages on both sides. The militia in the London district is called out. Civilians harry the troops. Farmers leave their fields and flock into Burlington Heights and to Twenty Mile Creek, where Major-General Riall has his headquarters.

The Canadian population is so hostile to the invaders that, in an act of revenge, the troops of Colonel Isaac Stone descend upon the Loyalist village of St. Davids and burn it to the ground. Brown, in one of his furies—and with bitter memories of the retaliation that followed McClure’s ravaging of Newark—dismisses Stone. The Colonel pleads that he, personally, was three miles away at the time, but Brown is not in a mood to accept excuses. The accountability for the outrage, he says, must rest with the senior officer. It is a harsh principle, indicative of Brown’s frustration.

He cannot even blockade Fort George from his position at Queenston. Parties continue to slip in and out of that thinly held garrison. On July 20, Brown—still expecting the fleet—moves his army up before the fort, a move urged by the aggressive Winfield Scott against the advice of most senior officers.

But Scott can do no wrong in Brown’s eyes. Hanks, the drummer

boy, watches wide-eyed as the tall brigadier rides forward within range of the British cannon, telescope in hand, to reconnoitre the fort. A shell buzzes toward him. Scott raises his sword, sights it at the bomb, sees that it will fall directly upon him, spurs his horse, wheels about and escapes. A moment later, the missile drops on the exact spot he has vacated.

Without siege guns, Brown realizes he can do nothing against the fort. Those guns are at Sackets Harbor and can be transported to the scene only by Chauncey’s fleet—and there is no sign of Chauncey. Chagrined, Brown moves his army back to Queenston, having lost two days in a pointless exercise. At last, on July 23, he learns the hard truth: a letter from Sackets Harbor makes it clear he will get no help from the navy.

The odds have changed dramatically. Brown’s army has been reduced to twenty-six hundred effective soldiers. But the British have somewhere between three and four thousand. Lieutenant-General Drummond is on his way from York to take personal command. Morrison’s 89th has arrived to reinforce Riall. The British have sent troops across the Niagara to the American side, apparently planning to march up the river and threaten Brown’s flank and rear. All of Brown’s reserve supplies are at Fort Schlosser, in the direct path of this movement. Brown loses no time. On July 24, he moves back to Chippawa. There he will attempt to refit and reinforce his army and, leaving both forts in British hands, bypass them and move up the peninsula to seize Burlington Heights.

The zealous Winfield Scott does not want to wait. So eager is he for the contest that he wants to move on Burlington that very night. Brown restrains him. Sometimes Scott is

too

eager, a failing that will be brought home to both men in less than twenty-four hours at the junction of Portage Road and Lundy’s Lane.

CHIPPAWA, UPPER CANADA, JULY 25, 1814

It is five o’clock of a sultry day, the Americans at rest or drill, bathing, washing clothes, checking arms. David Douglass watches curiously

as Winfield Scott’s brigade heads out in column across the creek in the direction of the Falls.

His friend and superior, Colonel Eleazer Wood, explains what is happening. The British are believed to be crossing the Niagara at Queenston to seize Lewiston, dash upriver, overwhelm the American depot at Fort Schlosser opposite the American camp, and threaten Brown’s army. More troops are thought to be moving toward the American camp on the Canadian side. Scott has been ordered to march on Queenston—an action designed to force the enemy back to the Canadian side of the river—and report on the British dispositions.

Douglass, eager to be part of the action, gets permission to ride with Wood in the vanguard of Scott’s brigade.

Actually, the Americans are misinformed. Brown has been operating on rumour. He is convinced that the main British attack will come on his supply depot at Schlosser, directly across the river, but Gordon Drummond, now on the scene, has cancelled that movement. In fact, his deputy, Riall, is massing British troops three miles away at Lundy’s Lane, the main route between the Falls and the head of Lake Ontario. Riall has established a strong defensive force on this road to keep watch on the American camp at Chippawa. Drummond, meanwhile, having landed at the mouth of the Niagara, is marching to Riall’s aid with eight hundred men.

Brown’s weakness is his stubbornness and inflexibility. He finds it difficult to change his mind once it becomes fixed—a trait that has been impressed on the unfortunate Captain Treat and also on the cautious brigadier, Ripley. Earlier in the day, Colonel Henry Leavenworth, officer of the day, reported seeing two companies of British infantry and a troop of dragoons at Wilson’s Tavern near the Falls. Leavenworth tries to warn Brown that these must be the advance guard of the British army; he cannot believe that Drummond would trust such a force so close to the enemy without sizeable support. But Brown cannot be budged. Off goes Scott toward Queenston with Nathan Towson’s artillery, dragoons and volunteers—upwards of twelve hundred men. But Riall has three times that number, with more on the way.

The widow Wilson’s tavern, one of the few buildings not burned by American partisans, overlooks the famous Table Rock, just above the Falls. As Scott’s column comes into view, David Douglass sees eight or ten British officers hastily mount their horses. Some ride off briskly, but three or four face about and coolly examine the advancing Americans through glasses. They wait until the column is within musket shot, whereupon their leader, an officer “of dignified and commanding mien,” waves a military salute, wheels and rides away. In the distance, through the woods beyond, Douglass can hear a series of bugle signals.

Wood and Douglass are the first men to enter the tavern.

“Oh, sirs!” cries Mrs. Wilson, “if you had only come a little sooner you would have caught them all.”

“Where are they and how many?”

“It is General Riall,” says the widow, “with eight hundred regulars, three hundred militia and Indians, and two pieces of artillery.”

At this moment Winfield Scott enters, questions the tavernkeeper closely, then sends Douglass back to camp with word that Scott is about to engage the British army at Lundy’s Lane.

It does not occur to the eager brigadier-general to wait for reinforcements from Brown or even to sound out the enemy’s strength. It is an axiom of warfare that one does not engage an entrenched enemy piecemeal. But the aggressive Scott moves forward blindly until, suddenly, he realizes that he is heavily outnumbered by the forces directly ahead of him. The widow Wilson’s information, perhaps by design, was deceptive.

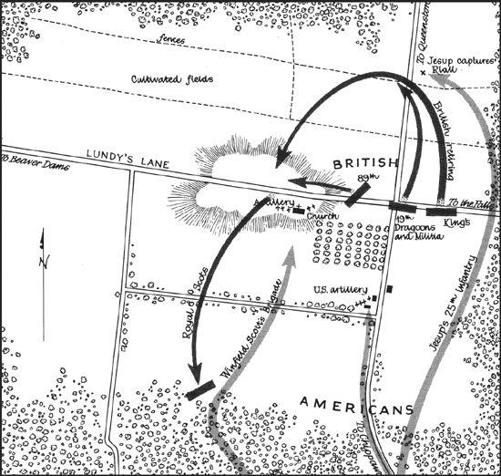

Scott is now within cannon shot of the red frame Presbyterian church, which occupies a high knoll one hundred yards to the left of the river road. To the right of the church is a small graveyard, and below it an orchard. The British hold the knoll and the ground around it, their line in the shape of a crescent with seven big field guns at the centre. Scott is caught in the curve of this crescent. Behind the ridge, Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond’s advancing reinforcements, including the veteran 89th, are already forming up.

What is Scott to do? Fall back? He does not know that Riall is preparing to do just that, believing, in his own blindness, that Brown’s entire army is before him. Only Drummond’s timely arrival countermands Riall’s order to withdraw.

Scott ponders. He is in a tight spot. If he advances he may be torn to shreds. If he turns back, he may panic the main army. There is another consideration, undoubtedly the paramount one for a man like Scott. He and his brigade have a reputation to uphold. His name is magic; his men can do no wrong. Can he suffer the ignominy of a retreat? A more cautious, less egotistical officer—Ripley, for one—might accept that. Scott cannot. He decides to push ahead against overwhelming odds, not waiting for Brown’s army, to glory, honour, and acclaim, even if it means the sacrifice of his brigade.

On his right, between road and river, is a thick wood. Scott orders Major Thomas Jesup to creep through this covering with his battalion, work around the British flank, and seize the Queenston road in the rear. With the support of Towson’s artillery, he himself will lead a frontal assault on the hill.

Jesup finds a narrow trail through the woods, moves slowly forward, and, as darkness begins to fall, hits the British in the flank, driving back a detachment of militia and two troops of dragoons. He is about to cross the Queenston road to attack the batteries at the rear of the knoll when he realizes that more British reinforcements are on their way from Queenston. If he crosses the road, he will be caught between two bodies of the enemy. He switches plans, determines instead to harass the new arrivals.

It is now so dark that it is impossible to distinguish friend from foe. On Jesup’s flank, one of his captains is surprised by a party of men emerging from the gloom.

“Make way there, men, for the General,” a British voice barks out.

“Aye, aye, Sir!” comes the quick-thinking reply.

As his aide rides past, the Americans surround the British general and his staff.

“What does all this mean?” asks the astonished Riall.

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane: Phase 1

“You are prisoners, Sir,” comes the answer.

“But I am General Riall!”

“There is no doubt on that point; and I, Sir, am Captain Ketcham of the United States Army.”

Riall, bleeding from a wound that will cause him to lose his arm, mutters, half to himself:

“Captain Ketcham!

Ketcham!

Well, you

have

caught us, sure enough.”

Jesup’s prisoners, who include Drummond’s aide, Captain Robert Loring, are sent back to Scott, eliciting a cheer from his hard-pressed brigade. For Scott is in trouble, his three battalions torn to pieces by the cannon fire of the British. The 22nd, its colonel badly wounded, breaks and runs into the 11th in the act of wheeling. That battalion breaks too, its platoons scattering, all its captains killed or wounded,

its ammunition expended. The brigade has been reduced to a single battalion, the badly mauled 9th, reinforced by a few remnants of the beaten regiments. The attack is a failure.

British reinforcements are pouring in—Drummond’s detachment from Queenston, another twelve hundred from Twelve Mile Creek. Winfield Scott can only hope that his message has got through to Brown and aid is on its way.

David Bates Douglass, his horse lathered, crosses the Chippawa bridge, the distant sound of cannon fire assaulting his ears, and reports directly to Major-General Brown, who immediately orders out Ripley’s brigade to reinforce the embattled Scott. He does not, however, immediately send off Porter’s Pennsylvania militia; clearly the stubborn commander is not yet convinced that the entire British force on the Niagara frontier is engaged at Lundy’s Lane. And so the American army goes into battle piecemeal.

Douglass’s commander, Colonel William McRee, sends him back to the scene of the action. It is dark when he arrives at Wilson’s Tavern, brilliantly lit and ready to receive the wounded. He rides on, soon sees the dim outlines of a hill surmounted by flashing cannon. Wounded soldiers limp past as he gallops on, the balls whizzing over his head, knocking the limbs off trees.

As Douglass reaches Scott’s lines, Colonel McRee overtakes him.

“Come,” says McRee, “let’s see what these fellows are doing.”

The two ride down to the left of the action, guided in the pitch dark by the flash of musketry. McRee spurs his horse directly toward the British lines, draws up at the foot of the knoll, examines the action, turns to his junior.

“That hill is the key to the position and must be taken,” he says.

Brown gallops up. Ripley’s force is not far behind, the men advancing on the run to keep up with their mounted leader. It is Brown’s intention to withdraw Scott’s shattered brigade and to move Ripley’s fresh troops into line. A wan moon, half obscured by the smoke of

battle, occasionally reveals the carnage on the hill above—heaps of corpses, grey uniforms intermingled with scarlet.