Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (108 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

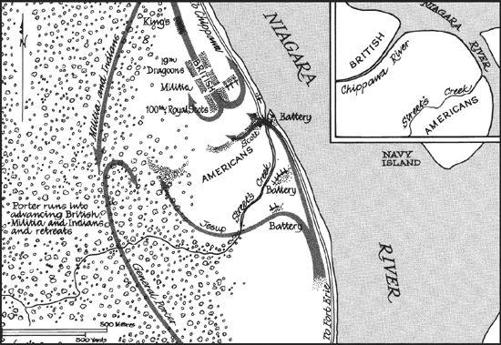

Riall has been on the gallop since eight in the morning, gathering his troops and dispatching appeals to York for reinforcements. At the British camp on the north side of the Chippawa, all is fever and bustle as troops and refugees pour in. Riall’s defensive position is well chosen, for the sluggish creek is unfordable, and there is no other bridge for miles upstream. The Chippawa cuts the peninsula in two: no invading force can roll up the frontier without seizing and holding this bridge.

To frustrate such an attempt, Riall has his army dug in on the north side of the creek and an artillery battery on the south side amid a cluster of houses and warehouses that forms the community of Chippawa. The settlement marks the southern terminus of the portage route around Niagara Falls, where schooners and wagon trains switch cargoes to circumvent the great cataract. Tomorrow it will be a battlefield. The residents have already fled to the protection of the British camp, and a long line of refugees snakes along behind.

For more than twelve months these victims of a baffling and mysterious war—old men, women, small children—have been harassed and plundered by raiding parties from across the river. Their horses are spavined, for the best animals have all been stolen or eaten. The remaining wagons are broken down. Everything of value has long since been taken—livestock, flour, bacon, household goods, silverware, cutlery. Half starved through the winter, their able-bodied

men seconded to the militia, their fields sometimes unsown, oftener ravaged, they cross the bridge and seek a camping place in the open fields beyond the British lines.

As dusk falls, Winfield Scott’s advance brigade is reinforced by Ripley. A force of Pennsylvania militia under Peter B. Porter is also on the way. By noon the following day, Jacob Brown will have five thousand fighting men and Seneca Indians to contest the bridge at the Chippawa. Riall will have two thousand. As midnight approaches and more reinforcements straggle into camp and bed down, the two armies, more than a mile apart, slumber and await the approach of a bloody tomorrow.

CHIPPAWA, UPPER CANADA, JULY 5, 1814

It is seven o’clock of a bright midsummer morning. Captain Joseph Treat of the U. S. 21st Infantry has been up all night on picket duty. He is lame, worn down by fatigue and burdened by extra responsibility, for the second-in-command of his company is not only ill but also under arrest. As well, a fall from a horse a few days earlier has rendered him unfit for duty. But he has refused to report sick and has marched with his regiment to Street’s Creek.

As the lemon sun begins to warm the meadows along the Niagara, an order reaches him to march his forty men back to camp. Comes a rattle of musketry from the British picket lines. Treat’s men throw themselves to the ground, hidden in the waist-high grass. He orders them to their feet, but when the enemy fires again his new recruits break and run toward the rear, directly into the muzzles of their own cannon.

Treat, running after his men, calls on them to halt, form up, return and face the enemy. At this moment, Major-General Jacob Brown arrives on the scene.

The new commander of the Army of the North is a big, handsome figure, with a smooth oval face and clear searching eyes. He comes from a long line of Pennsylvania Quaker farmers but has also been schoolmaster, surveyor, land speculator, and—more significantly—a

smuggler. Smuggling is an honourable calling in Sackets Harbor, Brown’s home; most of the male populace engages in it. Brown, however, is no minor smuggler. A road is named for him, Brown’s Smuggler’s Road, and his nickname, “Potash Brown,” comes directly from the illicit potash trade across the border. His smuggler’s resourcefulness—aggressive action, swift decisions—has already stood him in good stead as an army commander; he is several cuts above the posturing and indecisive leaders he has replaced. Quick to act, he is also quick to anger—too quick, sometimes. His worst fault is a refusal ever to admit he is wrong. Now he is enraged at what he sees: an officer running away with his men in the face of enemy fire. As Treat tries vainly to explain, his sergeant runs up to report that one of the men hiding in the grass has not risen. Brown is aghast: a wounded man deserted by his cowardly officer! Captain Treat again tries to explain, but Brown brusquely sends him off to bring back the wounded man, then strips him of command, charges him with cowardice, and rides away. Treat is outraged; it will take ten months and all his persistence to clear his name.

All that morning, to Brown’s annoyance, the skirmishing continues. The Americans are camped on the south side of Street’s Creek, the British on the north side of the Chippawa. Between these two streams lies an empty plain, three-quarters of a mile wide, bordered on the east by the river, on the west by a forest. At noon, Brown determines to clear the forest of British pickets—Indians and militia—who are exposing his whole camp to a troublesome fire.

He decides to employ Peter B. Porter’s mixed brigade of Indians and Pennsylvania militia who, having crossed the river at midnight, are marching toward the camp. He rides out to meet them and explains his plan.

Porter is touchy where the militia are concerned and jealous of the regulars who, he believes, get better treatment than his civilian army. Brown flatters him, explaining that it is necessary to drive the British out of the forest and that the militia and Indians are better equipped for bush fighting than the regulars.

Porter suspects he is about to become a sacrificial goat. He can see no prospect of glory in this kind of skirmish, which can end only in retreat. And Porter desperately needs a moment of glory after the humiliations visited on him at Black Rock. (Can he ever forget being forced from his home in his nightshirt?) He is a pugnacious man with a pugnacious face—bulldog nose, snapping black eyes—pugnacious in politics (Henry Clay’s leading War Hawk) and pugnacious in war. He does not lack zeal: he has scoured the countryside for volunteers, not always with success. Almost half of his Pennsylvanians have refused to cross into Canada—another setback to add to his litany of mortifications. But he has, by dint of oratory and persuasion, managed to attract four hundred Senecas to the American cause.

Brown hastens to assure the belligerent militia general that there is not a single British regular on the south side of the Chippawa-only militia. At the moment this is true. Further, he promises that Winfield Scott’s brigade will cover Porter’s right in case the British should attack.

Porter agrees. The Pennsylvanians are less than enthusiastic. Their rations have been left behind. At two o’clock the troops are given two biscuits per man, the first food they have eaten that day. Captain Samuel White, who expects to enjoy a good supper later on, gives one of his biscuits away, only to learn, belatedly, of the projected attack. When Porter calls for volunteers, White and two other officers, with some 150 others, volunteer as privates.

White watches in fascination as the Indians tie up their heads with yards of white muslin, then paint their faces, making red streaks above the eyes and forehead, rubbing their hands on burnt stumps to streak charcoal down their cheeks. That accomplished, Porter leads his force of several hundred in single file through the woods on the left.

He does not know, of course, that Phineas Riall, the British commander, has decided to mount an all-out attack on the American position. Riall has sent a screen of militia and Mohawks under John Norton to cover his right flank in the same woods through which

Porter’s men are advancing. At the same time he is forming up his regulars to cross the Chippawa bridge and advance against Jacob Brown’s army.

Riall is a Tipperary Irishman, short, stout, near-sighted, gutsy, but without much fighting experience. He is impetuous to the point of rashness. He has badly underestimated the size of the enemy force and believes, wrongly, that the enemy plans a two-pronged attack, with Chauncey’s fleet bombarding the lakeshore above Newark. Consequently, he has weakened his force by sending a regiment back to Queenston. Yet he does not order out the militia from the neighbouring countryside or call on the 103rd Regiment, eight hundred strong, at Burlington Heights, which could be rushed to the scene within two days. When the three hundred members of the exhausted and badly mauled King’s Regiment arrives from York early in the morning, Riall decides he has an army strong enough to attack.

Besides the King’s, he has two regular regiments: the Royal Scots under Lieutenant-Colonel John Gordon and the 100th under the remarkable Marquis of Tweeddale, a physical giant, famous as a swordsman, horseman, gambler, and fox hunter, thrice wounded under Wellington, limping from a game leg. A recent arrival, Lord Tweeddale comes to Canada with a towering reputation for chivalry, dash, and eccentricity. Stories about him are rife in the camp: how, on one memorable long march with Irish recruits, he appointed a rearguard with shillelaghs to hurry on the laggards; how he knocks his men down when they get drunk, bails them out when they are in trouble, thinks nothing of leaping from his horse and shouldering a private soldier’s knapsack to march as an example to his troops; how he once risked his life under fire to swim a river and rescue the wife of a German hussar, forgotten during a retreat. His baggage on the Peninsula included cases of champagne and claret, which he often served in his own mess to captured officers. At his waist he carries two pistols presented by Wellington himself following a cavalry action.

Lord Tweeddale is in bed, suffering from a violent case of ague—a vague term that could mean anything from influenza to

malaria—when he receives Riall’s order. He replies that he is “in the cold fit of the disease” but expects the hot fit shortly. Riall agrees to postpone the attack for an hour when, presumably, the Marquis will be hot enough for action. By four o’clock the troops are drawn up on a plain between the two creeks, hidden from the Americans by a screen of bushes along the Chippawa.

At this moment, Peter B. Porter is moving his men in file through the woods, blissfully unaware of his predicament. Just ahead, masked by trees and underbrush, a strong enemy column is advancing toward him. A few yards to his right, on the plain beyond the forest’s rim, Riall’s scarlet-coated regulars are drawn up in battle order, bayonets gleaming. When he realizes that he is caught between the two forces, Porter shouts the traditional cry:

“Sauve qui peut.”

In an instant his column is in full retreat, the Indians bounding ahead, many carrying their small sons, whom they have brought into battle, on their shoulders. Porter himself is scarcely able to keep ahead of the pursuing British until he reaches the safety of Street’s Creek. Once again, the bellicose congressman has been frustrated in his search for glory.

The Battle of Chippawa

Not all of his men outrun the enemy. Captain Samuel White, who volunteered to fight as a private under Porter, is surrounded by enemy Indians with two fellow officers from the Pennsylvania militia, Lieutenant-Colonel John Bull and a Major Galloway. An Indian seizes his coat, another his vest, a third his neck-cloth. Soon he is stripped to his shirt and pantaloons. Everything including his watch is taken.

Galloway has lost his boots and must walk barefoot. A more ghastly fate awaits the Colonel. The party has proceeded less than half a mile to the rear when one of the guard whoops, raises his rifle, and shoots him through the body. Bull falls, reaches out to Galloway for help, and is dealt a tomahawk blow through the skull. His captors scalp him and leave the corpse where it fell. As they hurry their two remaining prisoners through the woods, White expects a similar fate at any moment. A vagrant thought courses through his mind: why hadn’t he eaten the second biscuit in his rations while he had the chance? If he lives, he is unlikely to have supper.

Major-General Jacob Brown sees the clouds of dust and hears the firing in the forest. He rightly concludes that the British are moving to the attack. It is five o’clock. Winfield Scott, in full uniform, has decided, in the cool of the afternoon, to drill his brigade in grand evolutions on Dan Street’s meadow. But now his commander dashes up on horseback.