Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (20 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

If the bespectacled “Hud” Allison and his wife had heard rumors of Molson’s mistress, they would have chosen to ignore them, since they were a quiet and conservative young couple, actively involved in church work at Montreal’s Douglas Methodist Church. While in England, they had arranged for their baby son, Trevor, to be baptized at a church in Epworth where Methodism’s founder John Wesley had once preached. In London, Hudson Allison had attended a directors’ meeting of the British Lumber Corporation, and it was perhaps there that he had encountered Peuchen and agreed to share a table with him on the

Titanic

during the crossing home.

While in his early twenties, Hudson Allison had spent two years in Winnipeg, where he had gotten to know some of the other Canadians now traveling in Peuchen’s shipboard coterie—Thomson Beattie of the “Musketeers,” for one, as well as the real-estate magnate Mark Fortune and his family. Mark Fortune had arrived in Winnipeg in 1871 when it was little more than a fur-trading outpost and he was a young man from rural Ontario sporting a name and an ambition worthy of a Horatio Alger story. He had shrewdly acquired a thousand acres of land through which Portage Avenue, the burgeoning city’s main street, would eventually pass, an investment that would earn him a fortune to match his name. By 1911 Fortune had also made his mark as a city councilor and had built a grand pseudo-Tudor mansion in the city’s poshest neighborhood. The following year he decided to take his wife, Mary; nineteen-year-old son, Charles; and three of his daughters, Ethel, twenty-eight, Alice, twenty-four, and Mabel, twenty-three; on a grand tour of Europe.

On the crossing from New York in January aboard the

Franconia

, Alice Fortune had found an admirer in William Sloper, an affable young banker’s son from New Britain, Connecticut, who found her to be “

a very pretty girl and an excellent dancing partner.” Yet the twenty-eight-year-old Sloper was not about to tie himself down to just one girl on this trip of a lifetime. As he recalled in a memoir, there was also the “vivacious, good-looking niece” of a Connecticut couple who caught his fancy, along with “two attractive sisters from Chicago” whom he agreed to join for a few weeks on the Riviera in the spring. But before that there was a Mediterranean cruise to enjoy, followed by an excursion down the Nile. The first stop in Egypt for most tourists was Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo, and when Sloper arrived there in February, he found that the Fortune family was already staying there. He joined them for drinks on the terrace one afternoon, and Alice Fortune soon noticed a small Indian man in a maroon fez waving his hands at them through the terrace balustrades and sent Sloper to fetch him. The Indian proved to be a fortune-teller who, while gazing at Alice’s palm, proclaimed, “

You are in danger every time you travel on the sea, for I see you adrift on the ocean in an open boat. You will lose everything but your life. You will be saved but others will be lost.” This doleful prediction was immediately dismissed with a laugh, and the little fakir was quickly paid and dispatched.

Sloper soon left Cairo on a Nile steamer with the Connecticut couple and their vivacious niece, while the Fortunes and “the Three Musketeers” set off on their own river excursion. They would not see each other again until Sunday, April 7, in London, when Sloper spotted the Fortunes taking tea in the Palm Court of the Carlton Hotel on Pall Mall. “

When are you going home?” was Alice’s first question after he had joined them. Sloper replied that he had just booked a ticket on the

Mauretania

for Saturday. Alice suggested he try and change his ticket to the

Titanic

, which was sailing on Wednesday, and assured him there would be at least twenty people he knew from the

Franconia

on board. She also agreed to join him the following night for dinner and the theater. When Sloper called on her at the Carlton on Monday evening, he proudly announced that he had booked a stateroom on the

Titanic

. “You have forgotten that I am a dangerous person to travel with,” Alice replied playfully, reminding him of the fortune-teller’s prediction in Cairo. Sloper was merely amused at this and on Wednesday morning he met the Fortunes at Waterloo Station to board the Boat Train for Southampton.

BY FOUR O’CLOCK

on Saturday, Daisy Spedden had finished her last hand of cards with Jim Smith and decided to have a tea tray brought to her in the lounge. After tea, she chatted with Malvina Cornell, the wife of a New York judge, and her sister Caroline Brown, whose husband was a partner in the Boston publishing firm of Little, Brown. A third sister, fifty-three-year-old Charlotte Appleton, was also on board, as the three women were returning from the funeral in England of an elder sister who had married a British diplomat. Archibald Gracie’s wife was a friend of “the Lamson sisters,” as these women had once been known, and on meeting them while boarding in Southampton, Gracie had volunteered to be their male “protector” on board, the same quaintly gallant service he had offered to Mrs. Candee. He later met a fourth and younger member of this all-female coterie, thirty-six-year-old Edith Corse Evans, a relation by marriage to Malvina Cornell, who boarded in Cherbourg. “

How little did I know of the responsibility I took upon myself for their safety,” Gracie would later write regarding these four women.

In the late afternoon, the decks began to fill up once again with passengers taking their pre-dinner exercise. Norris Williams and his father had walked on the boat deck that afternoon in their fur coats, and Norris recalled that the main topic of conversation among those they met was “

the speed of the boat and how she would prove by far the most popular boat on the ocean.” As the sun headed toward the Atlantic horizon for another end-of-day display, Steward Fletcher put his bugle to his lips to signal that it was time for passengers to dress for what would be the

Titanic

’s penultimate dinner.

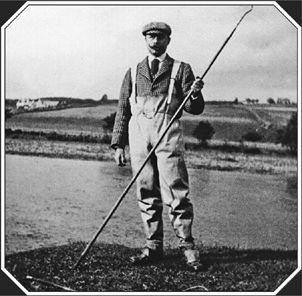

Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon, and her husband, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, seen fishing at his Aberdeenshire estate.

(photo credit 1.73)

W

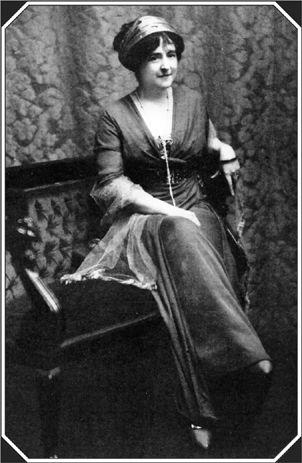

hile Helen Candee, Edith Rosenbaum, and Ninette Aubart contemplated which of their Paris-designed gowns they would don for Saturday’s dinner, some of the other first-class ladies were selecting dresses created by the most fashionable English couturiere, Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon. That the designer of their exquisitely finished Lucile gowns was actually on board was not something many of them realized, since she was traveling under an assumed name. On the passenger list a “Mr. and Mrs. Morgan” appear as the residents of portside cabins A-16 and A-20 when, in fact, these rooms were occupied by Sir Cosmo and Lady Duff Gordon.

The “Morgan” pseudonym was likely employed to allow the Duff Gordons a quiet crossing, free from a flurry of shipboard invitations that would have required Lucile to spend her time charming the wealthy ladies who formed so much of her clientele. And for her husband, a reserved Scottish baronet, seven days of making small talk with ostentatious Americans would have been a week of purgatory. Sir Cosmo particularly detested the New York reporters who would be waiting at the pier to pester his wife with impertinent questions if they knew that she was on board. Lucile did not travel often with her husband, but this trip required his steady business hand as she was about to negotiate the lease for larger premises for the New York branch of Lucile Ltd. It was business that had first brought them together—Cosmo had invested in her fledgling fashion house in 1895—but he had soon become captivated by the small, spirited woman behind the enterprise. His mother, however, was adamantly opposed to a “scandalous union” with a divorcée, so they were not married until after her death in 1900.

Like Helen Candee, Lucile had made an unfortunate first marriage. At the age of twenty-one she had married James Stuart Wallace, a wine merchant who was twenty years her senior. Wallace soon displayed an excessive fondness for the product he sold and was serially unfaithful, giving Lucile what she called the worst six years she ever knew. After he abandoned her for a music hall dancer, she was determined to divorce him, an action that at the time was both expensive and stigmatizing for a woman. Left with a young daughter and no source of income, Lucy (as she was familiarly known) realized she must find work, though options for genteel women were limited. But soon she had an idea. “

One morning when I was making a little dress for [daughter] Esmé,” she wrote, “I had a flash of inspiration. Whatever I could or could not do, I could make clothes. I would be a dressmaker.”

Lucy could indeed make clothes—for most of her life it had been a necessity. Much of her childhood had been spent in Canada, in what was then the backwoods town of Guelph, Ontario. Her father, Douglas Sutherland, an engineer from Nova Scotia, had met her mother, Elinor Saunders, the daughter of the local magistrate, while working there in 1859 on the construction of the Grand Trunk railway line. Shortly after their marriage in 1861, engineering work took Sutherland first to New York, then to Brazil, and finally to Italy. His wife went with him but stayed in lodgings in London while he was working in Italy, and it was there that Lucy was born in June of 1863. The following year another daughter, Elinor, was born in October of 1864, but only five months later Douglas Sutherland fell ill with typhoid and died. His wife was forced to return to Canada with her two small girls and live with her family at a farm called Summerhill on the outskirts of Guelph.

The household at Summerhill was dominated by Lucy’s grandmother, a formidable Victorian matriarch in black bombazine who was determined to instill genteel manners in her granddaughters. Life could be rather drab in the gray limestone house on the hill, particularly during the long winter months, but each year was brightened by the arrival of

le tonneau bienvenue

, a barrel sent from Paris by the family’s French relatives. The two girls shivered with anticipation as the top of the barrel was pried off to reveal brightly colored dresses, silk stockings, ribboned bonnets, frothy lace petticoats, corsets, and even gloves and wigs. Most important for Lucy, there were bolts of cloth, the scraps from which she used to create outfits for her handmade dolls.