Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (24 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

In a quick recovery, Woolner interjected, “One of the women I most admire is this one,” noting Ida Straus walking arm in arm with her husband. “They have just finished a Marconi chat with their son, whose east-bound ship is talking to ours,” he added. The Strauses had indeed received a reply that afternoon from the Marconigram they had sent to the

Amerika

, an indication that operators Phillips and Bride had caught up with their message backlog. The

Titanic

’s Marconi Room had also received and relayed a wireless message that the

Amerika

had sent to the U.S. Hydrographic Office in Washington, D.C., reporting “

two large icebergs” in the same area as those already noted by the

Caronia

and the

Athinai

. Since this message concerned navigation, it should have been sent to the bridge, but it was not.

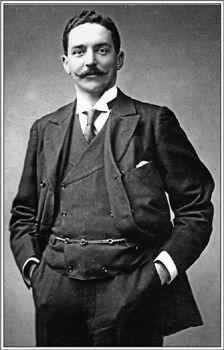

J. Bruce Ismay

(photo credit 1.54)

As the sun drew lower in the sky, Marian Thayer went to the B-deck cabin of her grieving friend Emily Ryerson to persuade her to come and see what promised to be a beautiful sunset. Until now, Mrs. Ryerson had not left her cabin except for some walks with her husband after dark when they were less likely to meet anyone. After strolling for about an hour, the two women settled into steamer chairs on the A-deck promenade, where J. Bruce Ismay unexpectedly joined them.

“

I hope you are comfortable and all right,” he said to Emily Ryerson as he seated himself on the next chair. She thanked him for providing an added stateroom and steward for her family, though she was in no mood for conversation and wished he would leave.

“We are in among the icebergs,” Ismay suddenly announced, in what Mrs. Ryerson called “his brusque manner.” He pulled out the message from the

Baltic

given to him earlier by the captain and held it up for her to see. “We are not going very fast, twenty or twenty-one knots,” he continued, “but we are going to start up some new boilers this evening.”

Mrs. Ryerson noticed a reference to the

Deutschland

(a German oil tanker) in the Marconigram and asked what that meant.

“It is the

Deutschland

wanting a tow, not under control,” Ismay replied.

When she inquired what he was going to do about this, Ismay answered that they were not going to do anything about it but instead would get into New York early and surprise everybody. When the two women’s husbands arrived, Ismay departed. Back in their stateroom, Emily Ryerson discussed with her husband what they would do if they arrived in New York on Tuesday night rather than Wednesday morning.

The message from the

Baltic

remained in Ismay’s pocket until Captain Smith ran into him in the smoking room at around seven-ten and asked for it back so he could post it in the chart room. The captain was already fully aware that ice lay ahead, and for this reason he had delayed the ship’s turning of “the corner,” the point at which it changed course to steam due west for the Nantucket Lightship, from 5:00 to 5:50 p.m. This set the

Titanic

on a course ten miles south of the normal shipping route. When Second Officer Lightoller came on duty at 6 p.m., he asked Sixth Officer James Moody to calculate what time they would reach the ice. Moody soon reported that it would be around eleven o’clock that evening.

With poignant symbolism, the

Titanic

’s final sunset was indeed its most beautiful. When Edith Rosenbaum went on deck that evening she noticed a group of men looking over the side toward the stern, admiring the reflection of the sunset on the water that was being thrown up from the propeller in “

a wide blood-red band from the ship’s side to the horizon.” She had been feeling the cold that afternoon in her cabin and soon noticed how frigid it had become out on deck.

By then “the Two” were seated snugly amid green cushions by the glowing fireplace in the lounge, where they were served tea and toast. It reminded Helen Candee of settling down before a home fire after a frosty afternoon ride over the fields. The Strauses came in and sat nearby and, on seeing Colonel Gracie in the room, told him of receiving a message in reply from the

Amerika

. When the bugle sounded at 6 p.m., the lounge began to clear as passengers returned to their staterooms to dress for dinner. One deck below, the Cardeza poker party broke up and the Harrises walked to the grand staircase to go down to their C-deck stateroom. Suddenly, René slipped on a greasy spot left by a dropped tea cake and, in her words, “

took a header down six or seven steps” and landed “in a heap at the foot of the stairs.” Several men, including Harry, rushed to her aid and lifted her up. “I knew that I was all right,” she recalled, “except for my right arm. I couldn’t bear to have it touched.”

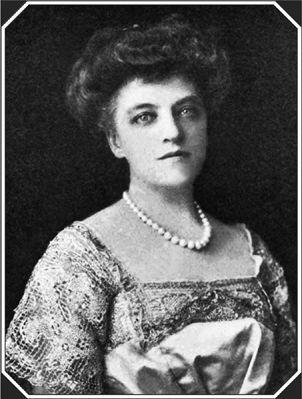

She insisted on walking to her stateroom, where Harry called for the ship’s doctor, William O’Loughlin. The “little doctor,” as René called him, pronounced the arm broken and began to prepare a cast where her arm would be held straight out. But René wanted a second opinion. She had heard that there was a New York orthopedic surgeon on board and, with apologies to Dr. O’Loughlin, asked if he could be consulted. Very soon the burly, bewhiskered figure of Dr. Henry Frauenthal, a specialist in joint diseases, arrived at their cabin door. He recommended that her arm be set with its elbow bent and the palm resting on her shoulder. After this was completed, bed rest was recommended, but René was determined to keep their dinner date with the Futrelles in the Ritz Restaurant. “Although I was suffering torture,” she recounted, “I knew I would feel it no less if I stayed in my room … so I struggled into my dinner dress—a sleeveless one, of course.” Meanwhile news of René’s accident had spread. “Before I left my room,” she recalled, “I had a dozen or more sympathetic messages.”

The evening gown that René struggled into was likely one that she had recently purchased in Paris. Her friend and table companion May Futrelle later recalled “

how fondly” the women wore their newly acquired Parisian finery that evening. And René’s tumble on the stairs may also have been fashion-related—the narrow, tapered “pencil” skirts then so much in style hampered movement and could have contributed to her becoming, quite literally, a fashion victim. Most constricting of all was the ankle-cinched “hobble” skirt championed by designer Paul Poiret, which had been much in vogue in 1910–11. In reaction, Lucile Duff Gordon had designed some of her “pencil” skirts with slits (discreetly covered with fabric) to allow for freer movement. But tapered skirts were for day wear only, and for this Sunday dinner, the most gala so far, the ladies in first class were selecting their showiest evening gowns. Helen Candee observed the women in the Palm Room “

shining in pale satins and clinging gauze” before dinner and spotted “the prettiest girl” in a “glittering frock of dancing length with silver fringe around her dainty white satin feet.” (Dorothy Gibson would later include just such a pair of white satin slippers in her lost luggage claim.) During the dressing hour, jewelry cases had been retrieved from the purser’s safe, and May Futrelle recalled how jewels flashed from the gowns of the women at dinner.

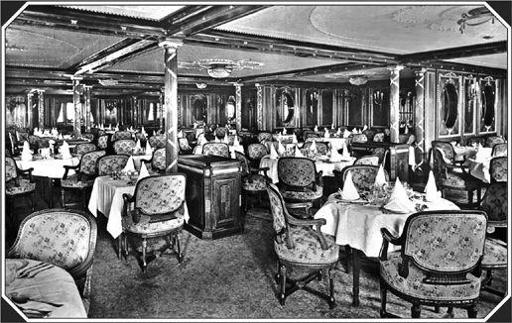

Eleanor Widener would probably have donned her famous multi-strand pearl necklace (valued at $250,000), since she and her husband and son Harry were hosting a dinner for Captain Smith in the Ritz Restaurant at seven-thirty that evening. They had invited their Philadelphia Main Line neighbors—the Thayers from Haverford and William Carter and his wife Lucile from Bryn Mawr. “Billy” Carter, thirty-six, was a keen horseman and polo player, and during the winter he and his family rented Rotherby Manor in Leicestershire so that he could take part in the many fox hunts held near Melton Mowbray. The Carters were returning to “Gwedna,” a large colonial-style mansion in Bryn Mawr, with their two children, three servants, two dogs, and a 25-horsepower Renault that was crated and stored in the forward hold. The ninth guest invited to the Wideners’ table was Archie Butt, who could be relied on to keep the conversation lively with witty stories and Washington gossip. For the evening, Archie likely selected his dress uniform, the same one he had worn for his audience with the pope, considering a show of gold lace to be appropriate for dining with the captain and the cream of Philadelphia society. Eleanor Widener would have conferred earlier with the restaurant’s manager, Signor Luigi Gatti, regarding the menu and placement for her guests in the elegant room, which, with its gilded Louis XVI décor, was remarkably similar in style to her own dining room at Lynnewood Hall.

As many of the passengers dressed for dinner, they noticed that the rhythm of the ship’s engines had increased, an indication that extra boilers had been lit and that an even better mileage tally might be posted at noon tomorrow. At 7:15 Seaman Samuel Hemming, one of the ship’s lamp trimmers, arrived on the bridge to report to First Officer Murdoch that all the ship’s navigation lights had been lit. Murdoch was then acting as officer of the watch since Lightoller had gone to the officer’s mess for dinner. As Hemming was leaving, Murdoch called him back and asked him to close the fore scuttle hatch on the forecastle deck since there was a glow coming from it. “

I want everything dark before the bridge,” Murdoch ordered in his Scottish-accented voice. With ice ahead, any ambient light could interfere with the lookouts’ ability to see clearly. The steamship

Californian

had advised at 6:30 p.m. that it had seen three large bergs five miles to the southwest, but this message wasn’t received by the

Titanic

’s Marconi Room. Junior operator Harold Bride was then writing up the day’s accounts and letting the equipment cool down after a very busy day. An hour later, when the transmitter was operating again, he intercepted the same message being sent from the

Californian

to the

Antillian

and delivered it to the bridge. By then Second Officer Lightoller had returned from dinner, and on his arrival, Murdoch had remarked on how the temperature had gone down four degrees, to thirty-nine degrees Fahrenheit, in the half hour that he had been gone. Within an hour it would drop to just above freezing.

The passengers, too, were aware of the plunging temperatures, and according to Margaret Brown, some of the women wore warm wraps over their evening dresses to dinner. There was much discussion that evening of the ship’s increased speed and the possibility of arriving earlier in New York. There was also talk that icebergs lay ahead. Yet, remarkably, there was no thought of any pending danger. As May Futrelle later wrote:

In the elegantly furnished drawing room [lounge], no premonitory shadow of death was present to cast a cold fear over the gaiety of the evening. It was a brilliant scene, women beautifully gowned, laughing and talking—the odor of flowers—ridiculous to think of danger. Why, it was just like being at some beautiful summer resort. There was not one chance in a million of an accident happening.

Eleanor Widener had reserved a table for nine in the Ritz Restaurant for a dinner in honor of Captain Smith.

(photo credit 1.74)