Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (16 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Smith himself would not marry until he was thirty-nine. His bride was the outgoing Bertha Barnes of Chicago, and for a time they were a popular couple in New York and Newport society. Bertha was an accomplished amateur musician and composer, and in 1904 she persuaded her husband that they should move to Paris. Once there, Bertha soon became well known in musical circles—particularly after she launched a popular all-female orchestra. Her husband was less at home in Paris and regularly boarded the liners to return to New York and the world he knew. This took a toll on the marriage and after a few years they were essentially living apart. In January of 1912, however, Bertha asked Jim to come to Paris and during that visit the couple were reconciled and Bertha agreed to come back to America and the Smithtown homestead. In April a family friend received a letter from Paris with the message “

Jim sails today on the great

Titanic

for New York to get ready the old home for Bertha, who follows in October.”

For someone who simply wanted the quiet life of a Long Island squire, fate had a way of finding Smith in the wrong place at the wrong time. Six years before boarding the

Titanic

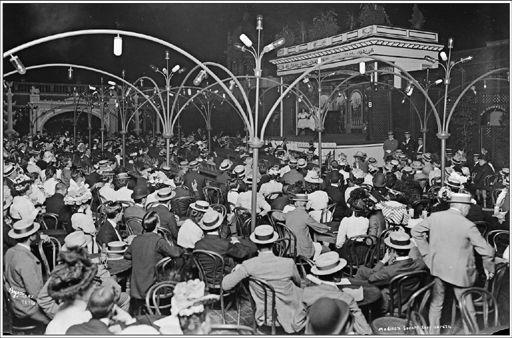

, he had been a witness to the very public murder of his brother-in-law, Stanford White, and had been required to give testimony at the most sensational murder trial of the new century. On the night of June 25, 1906, he was sitting alone at a table in the roof garden restaurant atop Madison Square Garden, a massive Moorish-style complex designed by his brother-in-law. Below him was the giant amphitheater he knew well from attending the annual New York Horse Show; it could hold fourteen thousand people, and Stanford White had once had it flooded to create a Venetian spectacle. Looming above Smith’s table, illuminated against the night sky, stood the building’s thirty-two-storey tower, topped by Saint-Gaudens’s golden statue of a naked Diana drawing her bow. For the roof garden, White had created a partly outdoor restaurant decorated with trellises, potted palms, and Japanese lanterns that were laid out around a stage where light cabaret was performed on summer evenings.

The roof garden restaurant (top) at Madison Square Garden (middle) was designed by Stanford White (above) as a venue for musical shows.

(photo credit 1.4)

(photo credit 1.37)

For lack of anything better to do on this hot June night, Jim was attending the premiere performance of a musical revue entitled

Mamzelle Champagne

. Not long after the show began, a man in evening dress and a long overcoat appeared at his table and asked if he could join him. His face was familiar and after he sat down Jim realized that he was Harry Thaw, the eccentric young millionaire from Pittsburgh whom people said was a cocaine addict or mad or both. Thaw offered Jim a cigar and began chatting about Wall Street and investments. The talk soon turned to travel and Jim mentioned that he was going abroad next week on the

Deutschland

. Thaw replied that he thought the

Deutschland

broke down too much and said he preferred the

Amerika

. Jim responded that he knew the captain of the

Deutschland

and that he was always very nice to Jim’s wife.

“

Where’s your wife?” Thaw asked.

“She’s in Paris.”

“Are you very much married?”

Jim asked what he meant by that.

Thaw pressed on, asking if he was “above meeting a very nice girl” and offered to fix him up with a “buxom brunette.”

Jim answered icily and turned away to watch the stage. So far

Mamzelle Champagne

didn’t have much fizz and there was distracted chatter at nearby tables. Thaw tried to restart the conversation but Smith was unresponsive so he eventually stood up and left. As the show limped onward, the pretty actress in the title role popped out of a giant champagne bottle, but even that generated only meager applause. Later, there was a mild stir as Stanford White passed through the crowd to take his usual table—he was a large, imposing figure and a famous one in New York. Everyone knew the man who had designed the Washington Square Arch, the Colony Club, the Villard Houses, and many other city landmarks. Onstage the lead tenor was singing “If I Could Love a Thousand Girls” while twenty girls from the chorus pranced about him. The architect beamed up at the chorus girls, his teeth flashing from beneath his outsized mustache.

Suddenly there was a gunshot, followed by another and another. Someone laughed, thinking it was part of the show, but then came a crash followed by a loud scream.

Stanford White’s body lay on the floor beside his toppled table, a pool of blood spreading across the white tablecloth twisted underneath him. Harry Thaw stood over him holding his revolver in the air. “

I did it because he ruined my wife!” he turned and shouted. “He had it coming to him. He took advantage of the girl and then deserted her!”

A New York City fireman had the presence of mind to relieve Thaw of his weapon which he meekly handed over. As the eerily placid gunman was escorted to the elevator, his young wife, Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, rushed forward and called out in disbelief, “Oh Harry, what have you done?”

Panicked Roof Garden patrons began streaming toward the exits and Jim Smith joined them. When he walked past the body he was unaware that the murder victim was his brother-in-law since White’s face was partially blown away and blackened by powder burns. Smith would soon learn the truth and by morning the murder was front-page news. With each edition came new revelations about White’s hidden life, accompanied by alluring photographs of the kittenish Evelyn Nesbit Thaw, whom White had reportedly known as a teenaged chorus girl before her marriage to Thaw. Newspaper circulations skyrocketed—never before had wealth, sex, and celebrity come together in quite such a perfect storm. To avoid curious crowds, White’s funeral was moved from Manhattan to Smithtown, and Jim Smith was one of the mourners who accompanied the body on the funeral train from New York to Long Island and then to the small clapboard Episcopal church in St. James.

By the time Harry Thaw’s trial began on January 23, 1907, Stanford White’s name had become notorious. Thaw’s tenacious widowed mother had hired a publicist to plant stories about White’s seductions of young girls and had even sponsored three plays depicting a thinly disguised White as a predatory monster. The strategy worked;

Vanity Fair

headlined one story

STANFORD WHITE, VOLUPTUARY AND PERVERT, DIES THE DEATH OF A DOG

. The man who had once personified the energy and ingenuity of the Gilded Age was decried from pulpits as a symbol of its excess and moral depravity.

At the trial, Jim Smith was a key prosecution witness and his description of Thaw’s lucid manner just prior to the shooting cast serious doubt on the defense’s claim of temporary insanity. Yet it was Evelyn Nesbit Thaw’s testimony that excited by far the greatest interest. Taking the stand in a demure blue suit with a white Peter Pan collar, she was described by one reporter as the “

the most exquisitely lovely human being I have ever looked at.” It was this remarkable loveliness that had made Evelyn a sought-after model for artists and photographers when she was only fourteen. It had then won her a spot in the chorus of the musical

Floradora

. Both Stanford White and Harry Thaw had left gifts and messages for her at the stage door, but it was White who had first taken the prize, thus igniting Thaw’s obsessive hatred.

Over a series of days in court, Evelyn would describe how White had won her over with his charm and attentiveness and had become a generous benefactor to her and her widowed mother and brother. She also described the architect’s studio hideaway on Twenty-fourth Street, exotically decorated with statuary, silken kimonos, a polar bear rug, a mirrored room, and most famously, a red velvet swing on which Evelyn would soar upward to kick at paper Japanese parasols. The most sensational part of Evelyn’s testimony was her description of how White had drugged her and taken her virginity when she was only sixteen. When this testimony was published, it caused a public outcry reminiscent of W. T. Stead’s “Maiden Tribute.” The White House was inundated with letters and telegrams demanding that President Roosevelt stop the newspapers from publishing such pornographic material, and in Congress a motion was introduced recommending that all publications containing “

the revolting details of this case” be banned from the U.S. mail system.

Evelyn Nesbit

(photo credit 1.38)

After four months, the trial ended with a deadlocked jury. The second trial began on June 6, 1908, and moved more quickly, concluding in less than four weeks. In his closing statement, the prosecutor reminded the jurors of how rationally Thaw had behaved at James Clinch Smith’s table only minutes before the murder. The jury, however, took just twenty-four hours to decide that Harry Thaw was not guilty on account of insanity. Thaw was taken to a state institution for the criminally insane where he was given comfortable accommodations until his release in 1915. Evelyn Nesbit pursued a slowly dwindling career as a vaudeville performer and silent film actress, and her later life was marked by alcoholism, morphine addiction, and suicide attempts. “

Stanny White was killed,” she once plaintively commented, “but my fate was worse. I lived.”

In

The Vanderbilt Era

, Louis Auchincloss compares the fury stirred up by the White-Thaw scandal to that caused by the trials of Oscar Wilde a decade before. “

There was surely a note of the philistine in it. ‘So that’s what these artist fellows are really up to!’ ” There are other similarities, too, between the writer who symbolized “the Yellow Nineties” and the architect who was the tastemaker for the Gilded Age. Both men were stalked by privileged, unbalanced, self-righteous pursuers, both were vilified for their sexual nonconformism, and both subscribed to the Bohemian credo that artists were not bound by the same rules as ordinary mortals. This view was embraced for a time by Frank Millet, as demonstrated in his unabashed love letters to Charles Warren Stoddard.