Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (8 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

The stunt was a huge success, as was the entire luncheon, and the presidential couple lingered to admire Archie’s Spanish furniture and the collection of Chinese fans he had acquired during his time in the Philippines. Archie’s description of this happy occasion, however, would comprise one of the last letters he sent to his mother, who would die only days later. Archie was devastated, for he was the most devoted of sons. His mother, widowed when he was twelve, had taken a library job at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, to help pay college fees for Archie and his younger brother, Lewis. She had died in England while visiting his older brother, Edward, and this distance made it even harder for Archie. He eventually hand-carried her ashes by train to Augusta, Georgia, for burial in the family plot. Later he would write to Clara that “

each day I seem to miss Mother the more and the awful fact that I will not see her again almost paralyzes my brain.”

The Roosevelts were extremely kind to Archie in his grief and the first lady arranged a cruise down the Potomac on the presidential yacht for his first day back. The president and his family, however, were soon packing up to leave the White House following the November election of William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s anointed successor. Butt had met Taft when he was governor of the Philippines, and it didn’t take long after the inauguration for Archie to be embraced by the new first family. “The big man,” as Archie called Taft, would come to regard his military aide “as if he were a son or brother.” Taft was a keen horseman and golfer, despite his three-hundred-pound girth, and Archie joined him in these pursuits and on his daily walks. He also accompanied the president, his wife, Helen “Nellie” Taft, and their teenaged daughter, Helen, when they sailed on the presidential yacht

Mayflower

and during visits to their summer home in Beverly, Massachusetts. One White House staffer nicknamed Archie “The Beloved,” and Taft came to rely on “The Beloved” even more after Nellie Taft suffered a stroke in May of 1909 and was unable to shoulder many of the first lady’s duties for some months afterward.

In 1911 Archie used his closeness to Taft to try to mend the rift that had developed between the new president and his predecessor. Right after Taft’s inauguration in March of ’09, Roosevelt and his son Kermit had departed for an African hunting expedition, and the former president did not return to America until June of 1910. In the midterm elections that November, the Democrats seized control of both the House and the Senate, which raised serious doubts about Taft’s ability to carry the White House for the Republicans in 1912. Taft soon became convinced that Roosevelt would challenge him for the nomination. The tireless Teddy was not a man for the sidelines and couldn’t stifle his disappointment at Taft’s timid continuance of his progressivist policies. Archie paid a peacemaking visit to Sagamore Hill on January 28, 1912, and afterward wrote to Clara that he didn’t think that Roosevelt would run. But only weeks later Roosevelt announced, “

My hat is in the ring.”

It is often written that the strain of trying to preserve his allegiances to both men pushed Archie to the brink of a nervous breakdown in early 1912. His letters, however, reveal that the reason for his low mood was a physical ailment brought on by stress and overwork. Archie had been at Taft’s side during a grueling precampaign swing through twenty-eight states in the fall of 1911. According to his own tally they were on the road for fifty-eight days and had made 220 stops, with 380 speeches by Taft, who had been seen by “

3,213,600 ear-splitting citizens.” (Archie was particularly incensed by “saucy little brats” who yelled out “Hello Fatty” to the president.) As he declared to Clara, “Do you wonder that our nerves have been disintegrated and that our innards are all upside down?” Archie’s innards were actually in serious trouble from “auto-intoxication,” a stress-induced illness that left him unable to digest food properly and caused ever-increasing levels of toxins to be released into his bloodstream. It was this illness that had caused the weight loss of twenty pounds that he had mentioned to the

New York Times

reporter, and it prompted friends to comment on how gaunt and ill he looked.

On February 23, 1912, Archie wrote to Clara of his decision to go to Rome for a little holiday with Frank Millet. “

I hate to leave the Big White Chief just at this time, though … if I am to go through this frightful summer I must have a rest now.” Loyal soldier that he was, Archie had decided to stick with Taft through the fall election. “

My devotion to the Colonel [Roosevelt] is as strong as it was the day he left, but this man [Taft] has been too fond of me for the past three years to be thrown over at this time.”

In an oft-quoted sentence from this same letter Archie tells Clara, “

Don’t forget that all my papers are in the storage warehouse and that if the old ship goes down you will find my affairs in shipshape condition.” Though this is often cited as a

Titanic

premonition, Archie then adds, “As I always write you in this way, whenever I go anywhere, you will not be bothered by presentiments now.” Archie’s time in Rome would prove to be restorative but his low and fatalistic moods continued to reappear. While staying with his cousin Rebie Rosenkranz in London before sailing, he had seemed to her husband to be “

in a depressed and sad state of mind … nerves he called it.” On his last full day in England he had suggested a visit to Westminster Abbey, saying, “If I do not see it now I shall never see it.” Yet Archie was not fatalistic about the

Titanic

, which he had heard was unsinkable, and in Father Browne’s photograph of him he is caught chatting amiably on A deck. So there is every reason to believe that at dinner on April 10, 1912, his customary affable nature was on display.

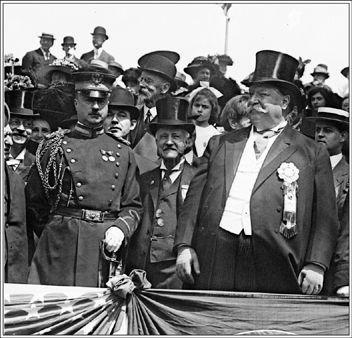

Major Butt (top, at left) was constantly at Taft’s side during official appearances. Following his illness, a thinner Archie (above, at right) accompanies the president on one of his daily walks.

(photo credit 1.34)

As an experienced transatlantic traveler, Archie knew to head for the dining saloon shortly after boarding to reserve a good table for the voyage, in this case for himself, Frank Millet, and his Washington friend, Clarence Moore. As the three men sat at table that evening, the conversation likely recapped Archie’s audiences with the pope and the king of Italy as well as his subsequent trip to England to see his older brother, Edward, a cotton trader who lived in Chester, near Liverpool. There was undoubtedly some talk of horses and dogs since Clarence Moore was a noted sportsman and former master of hounds at the exclusive Chevy Chase Hunt Club. He had just been scouring the north of England in search of a pack of good hounds and had purchased fifty pairs for the newly formed Rock Creek Hunt Club. Archie, too, was an ardent dog lover and the owner of some pointers that he kept kenneled with Moore’s dogs back in Washington.

Clarence Moore was a Washington banker and broker whose wisest investment had been to marry Mabelle Swift, the heiress to a Chicago meat-packing fortune. This helped him to acquire a substantial Beaux Arts mansion on the most fashionable stretch of Massachusetts Avenue and a gaily awninged seaside home called “Swiftmore” near the Taft summer White House at Beverly, Massachusetts. Moore had occasionally joined Archie for rounds of golf with “the big White Chief” at the Beverly country club.

Given Frank Millet’s delayed arrival, Archie and Clarence Moore likely chose to dine with him later in the dining saloon, perhaps in one of the room’s alcoves where backlit leaded-glass windows added to the atmosphere. “

It was hard to realize,” another passenger later wrote, “that one was not in some large and sumptuous hotel.” The menu, too, was large and sumptuous, reflecting the Edwardian fashion for elaborate multi-coursed meals—from hors d’oeuvres, soup, fish, fowl, and meat to a savory, a salad, and a selection of puddings and sweets. Archie’s doctor had prescribed a very restricted diet for him but as a lover of fine food he may have been tempted into “doing exactly as the doctors forbade” in the

Titanic

’s dining saloon.

Archie was an opera lover as well and no doubt recognized the tunes from

Cavalleria Rusticana

and

Tales of Hoffmann

wafting in from the musicians in the Palm Room. Millet, Moore, and Butt may have taken coffee there before repairing to the smoking room on A deck, their regular haunt throughout the voyage. The “smoke room,” as it was often called, was a popular place for masculine conversation and cards. Designed to emulate a Pall Mall men’s club, it featured mahogany paneling with mother-of-pearl inlay and hand-painted stained glass windows. Dark leather chairs were grouped around green-baized tables where card games were usually in progress. Above the glowing coal-burning fireplace, the only real one on board, was a painting by the maritime artist Norman Wilkinson of ships entering Plymouth harbor. Frank Millet likely gave it a close appraisal since a few years before he had painted a similar scene on the ceiling of Baltimore’s Customs House.

After a smoke and a hand of cards, Butt, Millet, and Moore probably called it a night. It had been a long day, after all. As they walked to their cabins, there was barely a movement as the ship made its steady course along the Channel’s southern reaches. Up in the crow’s nest on the foremast, lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee could see the lights of the French coast in the distance and the mast lights of other ships. For a closer look, binoculars would have helped, but the pair they had used in the crow’s nest on the trip from Belfast to Southampton had gone missing. This had been reported to Second Officer Charles Lightoller, but he had said there wasn’t a replacement set available. No one seemed bothered about it, so the lookouts weren’t worried either. Binoculars were not standard equipment in the crow’s nest on many ships. And these things just seemed to happen on a maiden voyage.

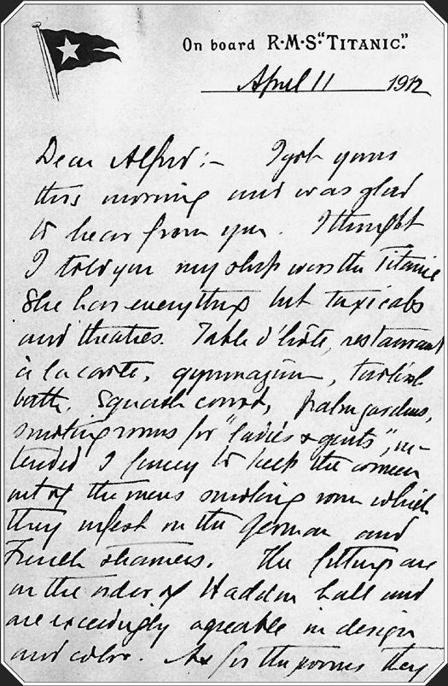

The first page of Frank Millet’s letter to Alfred Parsons. (For full text, see

this page

.)

(photo credit 1.91)