Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (18 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

Remarkably, there was another millionaire on board the

Titanic

who had also fallen for a twenty-four-year-old Paris cabaret singer and had also purchased a cabin so she could travel with him. The passenger in cabin C-90 was listed as “Mrs B. de Villiers,” but her real name was Berthe Mayné, though she sometimes used the stage name Bella Vielly. Berthe was actually Belgian, and it was in Brussels that she had met twenty-four-year-old Quigg Baxter, from Montreal. Quigg was sturdily built, handsome despite having lost an eye in a hockey game, quite rich, and besotted with her. He also spoke perfect French, though with an

accent Canadien

, since that was his mother’s first language.

Quigg’s mother, Hélène Baxter, was from an old Quebecois family that dated back to the time of Champlain. In 1882 she had married Quigg’s father, James Baxter, nicknamed “Diamond Jim,” who was of Ontario Irish stock but was busily making a fortune in Montreal as a diamond trader and banker. He eventually opened his own bank and built a twenty-eight-store retail development known as the Baxter Block. Diamond Jim was a bit of a rogue, and in 1900 he was sentenced to five years in prison for embezzlement. He died shortly after his release, and it was believed that by then most of his wealth was gone. But Baxter had cash squirreled away in Swiss bank accounts and in some investments in France and Belgium. The widowed Hélène soon made a habit of departing for Europe each fall to escape the Montreal winter and to keep an eye on her money. In November of 1911, she had sold the Baxter Block and sailed for Paris, taking her twenty-seven-year-old married daughter, Suzette, and younger son, Quigg, with her. For the trip home in April she had reserved one of the more elegant B-deck suites on the

Titanic

, unaware that Quigg had booked another cabin one deck down for his Belgian girlfriend. Whether he planned to marry Berthe in Montreal is unknown; the match would likely not have received

Maman

’s blessing—a Belgian newspaper had described the singer as being “

well-known in Brussels in circles of pleasure.”

For the first few days of the voyage, nausea had kept Hélène Baxter confined to her cabin, which allowed her son more time to spend with Berthe. On the evening of Friday, April 12, Quigg may also have chosen the Ritz Restaurant as the place for them to dine. But whether Ben Guggenheim and Quigg Baxter ever spoke or the two curiously similar couples even acknowledged each other on the

Titanic

is unknown.

AT 7:45 P.M

. on that Friday evening a wireless message was received from the captain of the French liner

La Touraine

saying that they had “

crossed [a] thick ice-field” and had then seen “another ice-field and two icebergs” and giving the positions of the ice and that of a derelict ship they had spotted. Captain Smith sent his thanks and compliments back and commented on the fine weather. While adding this information to the map in the chart room, Fourth Officer Boxhall remarked to the captain that

La Touraine

’s positions were of no use to them since French ships always took a more northerly course. “

They are out of our way,” he noted as the ship’s helmsman guided the new liner onward through the calm, dark sea.

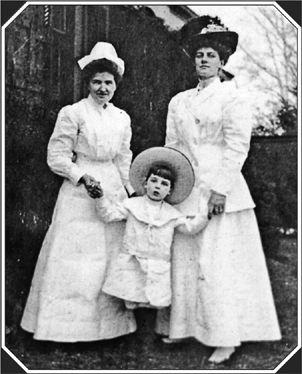

Daisy Spedden (at right) took her son’s nursemaid, Elizabeth Burns (left), for a Turkish bath on Saturday morning.

(photo credit 1.31)

I

took a

Turkish bath this morning,” Daisy Spedden recorded in her diary entry for April 13. “It was my

first

and will be my

last

, I hope, for I never disliked anything in my life so before, though I enjoyed the final plunge in the pool.” Daisy had taken “Miss B,” her son’s nursemaid, Elizabeth Burns, for what was probably her first steam bath as well—Turkish baths had been popular in Britain since the 1860s but were less common in the United States. Installing them on ships was a White Star innovation, the first having been introduced on the

Adriatic

in 1907. For their

Olympic

-class liners, White Star had decided that the baths would be a showpiece amenity and had decorated them in a style hailed in

The Shipbuilder

as evoking “

something of the grandeur of the mysterious East.”

At the entrance to the bath complex on F deck, Daisy and Miss Burns were given a complete set of towels and directed to the small changing rooms at the far end of the cooling room. Upon entering this room, the nurse and even her more-traveled employer were no doubt momentarily dazzled by the décor, which, from its gilded ceiling hung with bronze Arab lamps to its intricate tilework and fretted “Cairo” screens, was pure

Arabian Nights

fantasy. Once they were swathed and turbaned in white toweling, the first stop for most bathers was the elaborate weighing chair, a canvas seat encased in a gilded wooden bench with brass scales that printed out a ticket of one’s weight. From there, they proceeded to the temperate room for fifteen minutes or so of moderate dry heat, before advancing to the hot room, which was maintained at around two hundred degrees Fahrenheit. Daisy Spedden apparently soon fled the hot room to recline on one of the gilt-edged loungers in the cooling room, possibly taking a glass of water from the lion’s head faucet on the wall.

After a cooling shower or plunge in the pool, bathers then went into one of the two “shampoing” rooms for a full body wash in showers with an encircling spray. Each of these rooms also had a long marble slab where patrons could receive a horizontal shower massage from an invention called a “

blade douche,” an overhead pipe fitted with adjustable nozzles. The adjoining swimming pool in which Daisy Spedden took her plunge was filled with seawater warmed by heated salt water piped down from a tank on the boat deck. When finished, Daisy and Miss Burns likely returned to their cabins on E deck before heading to the dining saloon for luncheon—and the erasure of any weight loss shown on their post-bath weigh-in tickets.

Much of the talk at luncheon, once again, was of the miles the ship had covered; today’s posted tally was 519 nautical miles, besting yesterday’s mileage and pleasing those who had guessed as much in the betting pool. It was also the subject of an after-luncheon conversation between J. Bruce Ismay and Captain Smith that was overheard by a passenger named Elizabeth Lines. Mrs. Lines was yet another American in Paris; she had taken up residence there some years ago with her husband, a doctor and former medical director of the New York Life Insurance Company. With her sixteen-year-old daughter, Mary, Mrs. Lines was making the crossing to New York to attend her son’s graduation from Dartmouth College. After luncheon, as had become her custom, she took her coffee alone in the Palm Room, finding a table in a quiet corner. Before long, Captain Smith and Bruce Ismay sat down together on a nearby settee. Mrs. Lines recognized Ismay from when they had both lived in New York some years before and confirmed his identity with her table steward. She also noted that the White Star director was doing most of the talking while the captain merely nodded his assent. Ismay compared the

Titanic

’s mileage to the

Olympic

’s and expressed great satisfaction with the new liner’s performance. He repeated several times that he was certain they would make an even better run of it tomorrow as more boilers were lit. Finally, he smacked his hand down on the arm of the wicker settee and said emphatically, “

We will beat the

Olympic

and get in to New York on Tuesday!”

Mrs. Lines’s recollection of this conversation has been disputed by historians who feel that Ismay has been made a scapegoat for the sinking. They point out that arriving in New York on Tuesday night could have caused docking problems and would have disrupted passengers’ arrival plans, not to mention the ceremonious harbor welcome for the maiden crossing. Moreover, Captain Smith himself had said to the press after the

Olympic

’s maiden voyage, “

There will be no attempt to bring her in on Tuesday. She was built for a Wednesday ship.” Yet the New York arrival time was not measured by when the liner docked but by when it passed the Ambrose Lightship, a navigation beacon moored off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, where it marked the main channel into New York harbor. On her maiden voyage the

Olympic

had passed the Ambrose Lightship at 2:24 a.m. on Wednesday, June 21, 1911. Ismay knew that to beat the

Olympic

’s maiden crossing record and “arrive on Tuesday,” the

Titanic

had simply to pass the Ambrose Lightship before midnight and best her sister’s time by only two and a half hours. On her second westbound crossing, the

Olympic

had, in fact, reached the lightship at 10:08 p.m. on Tuesday, July 18. With the

Titanic

already achieving average speeds of just under twenty-two knots over the last two days, she was well on her way to making the Tuesday arrival that Ismay had so enthusiastically predicted.

DAISY SPEDDEN SPENT

most of Saturday afternoon playing cards with Jim Smith in the lounge. Smith and the Speddens moved in similar circles in New York society and even had a few relatives in common. Yet Daisy and Frederic Spedden were not drawn into the shipboard clique that Smith and his tablemates Archibald Gracie and Edward Kent had become part of by Saturday. To Walter Lord, this circle of seven people was “

one of those groups that sometimes happen on an Atlantic voyage, when the chemistry is just right and the members are inseparable.” Archibald Gracie dubbed them “our coterie.” The queen bee of “our coterie” was the Washington socialite and writer Helen Churchill Hungerford Candee. She was one of the “unprotected ladies” on board whom Colonel Gracie, adhering to a rather quaint practice, had offered to “safeguard.” In “Sealed Orders,” her account of the voyage published in

Collier’s Weekly

, Mrs. Candee would dub Gracie “the talkative man,” and she soon found that she had more in common with “the sensitive man,” the Buffalo architect Edward Kent, who shared her interest in antiques and interior decoration. The tall, genteel Kent, fifty-eight, a lifelong bachelor, was remembered by the writer Mabel Dodge Luhan as a man “

with a leaning toward beauty and lovely colors.”