What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (33 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

Here are a few steps for how you can stop overeating and get back in touch with hunger:

39

When you see something really tasty, ask yourself, “Do I need something in my stomach, or do I only want a taste in my mouth?” If just the taste, refuse.

Halfway through the main course, stop for a full minute. Ask yourself, “Am I full?” If you are, wrap the rest of the food and end the meal. If not, repeat this three-quarters of the way through.

Eat slowly and sip water frequently to slow down eating. Put your fork down between bites; this gives you a chance to consider if any more food is necessary to fill you up.

Finally, if you are an overeater, you probably eat all the food put before you. This is a very strong habit that must be broken. Excess food is essentially being thrown down the toilet or poured onto your midriff. I want you to do the

flushing exercise

to break this habit. Halfway through the main course of the next big meal you have at home, stop. Cut the rest of your food into pieces. Get the dessert, and cut it up too. Now flush it all down the toilet—this is where it will wind up, and this exercise allows you to skip the middleman.

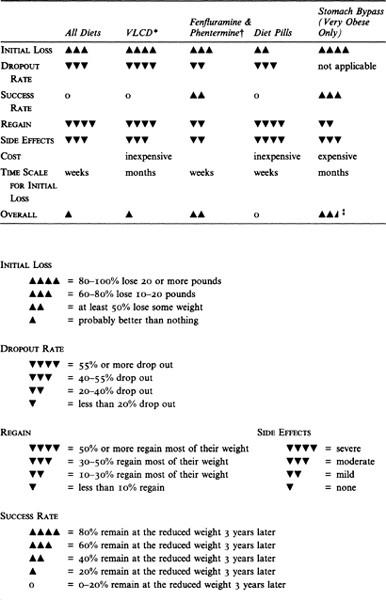

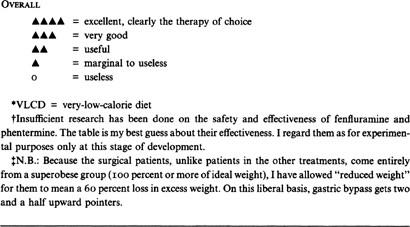

Surgery for the very obese

. Dieting has a poor outcome for the very obese. Most patients regain most of their weight in a few years, and this weight fluctuation itself carries a significant death risk. If you are very obese (double your “ideal” weight or more), you should consider surgery. The most successful operation is a stomach bypass (technically, a “Roux-en-Y gastric bypass”). This four-hour operation hooks your lower intestine to the top of your stomach. This is major surgery with a fair number of complications that must be corrected by more surgery. The mortality rate from the surgery is very low, below 1 percent, but do note that patients have a subsequent suicide rate of around 1 percent. The food you eat for the rest of your life must be soft, for it passes through your body less well digested. Appetite decreases, weight loss is dramatic, and, most important, the weight tends to stay off. In three-and five-year follow-ups of several hundred patients, the majority have done well. The patient who weighed three hundred pounds before surgery weighs only two hundred pounds five years later. Heart function also improves. Only about 15 to 20 percent fail completely and end up weighing close to their original weight. Gastric bypass is the only treatment of obesity with a documented satisfactory long-term outcome. The effect of this surgery on overweight people who are less than enormously obese is presently unknown, but given their desperation about overweight, I will not be surprised if moderately overweight Americans start to seek it out in the near future.

40

A Word to the Professional

I intend this book for two audiences. It is primarily for the consumer. Millions of people are trying to make rational decisions about how to cope with their problems and what to do about their shortcomings. They consume self-improvement regimens, psychological treatment, and psychiatric treatment to the tune of many billions of dollars annually. There is presently no consumer’s guide, nothing comprehensive and scientifically grounded, to tell the public which treatments work and which treatments fail, which problems can be conquered and which are intractable, which shortcomings can be improved and which cannot. Creating such a guide is my primary aim.

My second audience is the professional: the clinical and counseling psychologist, the psychiatrist, the social worker, the physician, the deliverer and designer of self-improvement programs. Dieting is a special case for us. It affects about half our clients, and it dwarfs all the rest of the problems we deal with by its sheer scale. For a half century we have been advising our clients to diet. Initially, our justification was sound: The “ideal weight” tables pointed to increased health risk with overweight. The situation has changed in the last twenty years. It is now clear that

weight is almost always regained after dieting

dieting has a number of destructive side effects including repeated failure and hopelessness, bulimia, depression, and fatigue

losing and regaining weight itself presents a health risk comparable to the risk of overweight

When we encourage dieting, we are in danger of violating our oath to “do no harm.” Help-givers should change their advice. We should tell our overweight clients that unless their only concern is short-term attractiveness, dieting is unlikely to work.

Commercial weight-loss plans, diet books, and magazine diets are under a more urgent obligation: They should warn their clients and their readers

emphatically

that any weight lost is likely to be regained. If commercial programs will not do this voluntarily, disclosure of their long-term success (or failure) rates and of their side effects should be a matter of law.

These steps will go a long way toward making our profession a more responsible one.

13

Alcohol

Poetry is the lie that makes life bearable.

R. P. Blackmuir (from a poetry lecture,

Princeton University, spring 1959)

F

IFTEEN YEARS AGO

two pioneering graduate students at the University of Pennsylvania—Lauren Alloy and Lyn Abramson—conducted an experiment that yielded the most annoying results I have seen in my scientific lifetime. For a decade I kept hoping their findings would be overturned, but subsequent studies confirmed them.

Subjects were given differing degrees of control over the lighting of a light. For some, the action they took perfectly controlled the light: It went on every time they pressed a button, and it never went on if they didn’t press. The others, though, had no control whatsoever: The light went on regardless of whether or not they pressed the button; they were helpless.

The people in both groups were asked to judge, as accurately as they could, how much control they had. Depressed people were very accurate. When they had control, they assessed it accurately, and when they did not have control, they said so. The nondepressed people astounded Alloy and Abramson: These subjects were accurate when they had control, but when they were helpless, they were undeterred—they still judged that they had a great deal of control. The depressed people knew the truth. The nondepressed people had benign illusions that they were not helpless when they actually were.

Alloy and Abramson wondered if maybe lights and button pushing did not matter enough, so they added money: When the light went on, the participants won money; when the light did not go on, they lost money. But the benign illusions of nondepressed people did not go away; in fact, they increased. Under one condition, where everyone had some control, the task was rigged so that everyone lost money. Here, nondepressed people said they had less control than they actually had. When the task was rigged so that everyone won money, nondepressed people said they had more control than they actually had. Depressed people, on the other hand, were rock solid, accurate whether they won or lost.

Supporting evidence confirms that depressed people are accurate judges of how much skill they have, whereas nondepressed people think they are much more skillful than others judge them to be (80 percent of American men think they are in the top half of social skills). Nondepressed people remember more good events than actually happened, and they forget the bad events. Depressed people are accurate about both. Nondepressed people believe that if it was a success, they did it, it is going to last, and, moreover, that they are good at everything; but if it was a failure, someone did it to them, it is going away quickly, and it was just this one little thing. Depressed people are evenhanded about success and failure. “Success has a thousand fathers, and failure is an orphan” is only true of the beliefs of nondepressives. In a follow-up study, Alloy found that nondepressed people who are realists go on to become depressed at a higher rate than nondepressed people who have these illusions of control.

1

Realism doesn’t just coexist with depression, it is a risk factor for depression, just as smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer.

It is a disturbing idea that depressed people see reality correctly while nondepressed people distort reality in a self-serving way. As a therapist I was trained to believe that it is my job to help a depressed patient to both feel happier and see the world more clearly. I am supposed to be the agent of happiness as well as the agent of truth. But maybe truth and happiness antagonize each other. Perhaps what we have considered good therapy for a depressed patient merely nurtures benign illusions, making the patient think that her world is better than it actually is.

This possibility is more than just disturbing when you flesh it out. It is downright subverting of one of our most cherished beliefs about therapy: that the therapist is the agent of both reality and health. For what other problems does good mental health depend on deluding oneself? For what other problems does cure depend on nurturing illusions rather than facing facts? Maybe the tactics that relieve a problem and the truth about the problem are not the same.

Nowhere is the antagonism between the tactics of recovery and the truth better seen than in problems of substance abuse. This chapter is about alcohol. I will not discuss other recreational drugs or cigarettes at any length, but all of what I have to say applies to the abuse of these substances as well.

Alcohol and Alcoholism

There is a disease called alcoholism.

An alcoholic is powerless before this illness.

Alcoholism is a physical addiction.

Alcoholism is a progressive disease.

Once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic.

There is an addictive personality.

One drink, and relapse is inevitable.

All of these statements are commonly believed. All of them are probably useful. People who abuse alcohol are better off believing them. People who try to help alcohol abusers can be more effective if they believe the statements to be true. Indeed, these beliefs are at the cornerstone of many self-help groups, including the granddaddy of all self-help groups, Alcoholics Anonymous.

Strangely, however, none of them is clearly true. At the very least, each is controversial; many scientists view these “truths” skeptically. Some view them as excusing misbehavior by relabeling it as a medical symptom (as

psychopathic

is substituted for

evil, kleptomaniac

for

thief, sexual deviant

for

rapist, pedophile

for

child molester, temporary insanity

for

murder)

, others view them as political slogans, and others say they are blatant falsehoods.

My primary job is to see if alcohol abuse is curable. Along the way, however, I cannot avoid looking at these beliefs. I will not be able to settle the controversies about alcoholism as a disease, an addiction, a bad habit, or a sin. I do not have the final word about the addictive personality, nor about controlled drinking. I will give you my opinion about these issues, but opinion is all it is. No false modesty here: While I am an authority on emotion, and an active researcher on sex and dieting, I am only an educated reader in the substance-abuse literature. I can give you the latest word, but my clinical and research experience in this field is limited.