What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (30 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

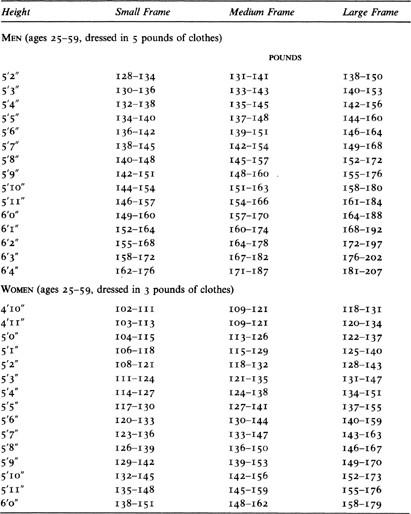

1983 METROPOLITAN LIFE INSURANCE HEIGHT AND WEIGHT TABLES

2

But the crucial claim is unsound because weight (at any given height) has a normal distribution,

normal

both in a statistical sense and in the biological sense. Why is there a distribution of weights at all? Why don’t all 64-inch-tall thirty-five-year-old women weigh 130 pounds? Some women fall on the heavy side of 130 pounds because they are heavy-boned, or buxom, or have slow metabolisms. Others fall there because they overeat and never exercise. In the biological sense, the couch potatoes can legitimately be called overweight, but the buxom, heavy-boned, slow people deemed overweight by the “ideal” table are at their natural and healthiest weight. If you are a 155-pound woman and 64 inches in height, you are “overweight” by around 15 pounds. This means nothing more than that the average 130-pound, 64-inch-tall woman lives somewhat longer than the average 155-pound woman of your height. It does not follow that if you slim down to 125 pounds,

you

will stand any better chance of living longer.

Here is an analogy. Imagine that fifty-year-old men who are gray-haired die sooner than fifty-year-old men who are not. If you are a gray-haired fifty-year-old, should you dye your hair? No, and for two reasons: First, whatever causes grayness may also cause dying sooner, and coloring your hair will add no time to your life because it doesn’t undo the underlying cause of dying sooner. Second, health damage caused by repeatedly coloring your hair with chemicals might itself shorten your life.

In spite of the insouciance with which dieting advice is dispensed, no one has properly investigated the question of whether slimming down to “ideal” weight produces longer life. The proper study would compare the longevity of people who are at their “ideal” weight without dieting to people who achieve their “ideal” weight by dieting. Without this study, the common medical advice that you should diet down to your “ideal” weight is simply unfounded.

3

This is not a quibble, for there is evidence that dieting damages your health and that this damage may shorten your life.

Myths of Overweight

The advice to diet down to your “ideal” weight in order to live longer is one myth of overweight. Here are some others:

Overweight people overeat

. Wrong. Nineteen out of twenty studies show that obese people consume no more calories each day than non-obese people. In one remarkable experiment, a group of very obese people dieted down to only 60 percent overweight and stayed there. They needed one hundred fewer calories a day to stay 60 percent overweight than normal people needed to stay at normal weight. Telling a fat person that if she would change her eating habits and eat “normally” she would lose weight is a lie. To lose weight and stay there, she will need to eat excruciatingly less than a normal person, probably for the rest of her life.

4

Overweight people have an overweight personality

. Wrong. Extensive research on personality and fatness has proved little. Obese people do not differ in any major personality style from nonobese people. They are not, for example, more susceptible to external food cues (the fragrance of garlic bread, for example) than nonobese people.

5

Physical inactivity is a major cause of obesity

. Probably not. Fat people are indeed less active than thin people, but the inactivity is probably caused more by the fatness than the other way around.

Overweight shows a lack of willpower

. This is the granddaddy of all the myths. When I am defeated by that piece of carrot cake, I feel like a failure: I should be able to control myself, and there is something morally wrong with me if I give in. Fatness is seen as shameful because we hold people responsible for their weight. Being overweight equates with being a weak-willed slob. We believe this primarily because we have seen plenty of people decide to lose weight and do so in a matter of weeks.

But almost everyone returns to the old weight after shedding pounds. Your body has a natural weight that it defends vigorously against dieting. The more diets tried, the harder the body works to defeat the next diet. Weight is in large part genetic. All this gives the lie to the “weak-willed” interpretation of overweight. More accurately, dieting pits the conscious will of the individual against a deeper, more vigilant opponent: the species’ biological defense against starvation. The conscious will can occasionally win battles—no carrot cake tonight, this month without carbohydrates—but it almost always loses the war.

The Demographics of Dieting

We are a culture obsessed with thinness. How many times a day do you think about your weight? Each time you catch a glimpse of your naked body or your double chin in the mirror? Each time you touch your midriff bulge? Each meal? Each time you eat something tasty and want more? Every time you’re hungry? My guess is that the average overweight adult (the large majority of us) thinks discontentedly about his or her body more than five times a day. By contrast, how many times a day do you think about your salary? My guess is once a day, or, if you are really strapped, about five times a day. Is being overweight as important as going broke?

You and I, and about 100 million other Americans, share this nagging discontent. In 1990, Americans spent more than $30 billion on the weight-loss industry, almost as much as the federal government spent on education, employment, and social services combined. These billions are poured into hospital diet clinics and commercial weight-loss programs, into health spas and exercise clubs, into 54 million copies of diet books. Ten billion dollars went for diet soft drinks. There were 100,000 jaw-wiring and liposuction operations at $3,500 each. More than $500 was spent on weight loss by each overweight adult in America. We would save this much if we could be convinced that we were not overweight or that there was nothing we could do about being overweight.

6

The fashion industry, the entertainment industry, and women’s magazines bombard us with female models of beauty and talent so thin as to represent almost no actual women in the population. We have gotten heavier and heavier, but the models have gotten thinner and thinner. From 1959 to 1978, the average

Playboy

centerfold became markedly more gaunt, and the average Miss America contestant dropped almost one-third of a pound a year. During the same twenty years, the average young American woman gained about the same amount. Both these trends have continued into the 1990s.

7

The purveyors of weight loss are the children of those pioneering advertising campaigners who in the first half of this century created and then preyed upon insecurity (“He said that she said that he had halitosis”). The weight-loss industry’s clout should not be underestimated. It has cornered the bulk of the self-improvement market and a sizable percentage of the American medical dollar. It is self-interested and powerful. It is pleased that the “ideal weight” tables put so many of us in the overweight category. It is delighted that Americans believe minor overweight is a serious health risk. It is ecstatic that men now find thin women sexier than voluptuous women. It thrives on the fact that Americans are so insecure in themselves and so desperately unhappy with their bodies. It has on its payrolls some of the most prominent scientists of appetite, who publish journal articles touting new, improved diets and exaggerating the health risks of overweight.

All this has created a general public that is discontent, even despairing, about their bodies, and willing—even eager—to spend a substantial portion of their earnings in the belief that they can and should become much thinner than they are. It is time for this to end.

The Oprah Effect

There is a professional consensus about two facts:

You can lose weight in a month or two on almost any diet.

You will almost certainly gain it back in a few years.

The American public watched in hopeful fascination as a daytime TV host, Oprah Winfrey, went on Optifast, which is, technically, a

VLCD (very-low-calorie diet)

. She became slimmer and slimmer before our eyes: 180, 160, 150, 140, 120. In a matter of months, she lost 67 pounds and looked trim and petite. Oprah praised the diet, and Optifast’s business soared. Over the next year, the viewing public watched in morbid fascination as Oprah went from no to 120 to 130, all the way back to 180. Embittered, Oprah condemned the diet, and Optifast’s business shrank.

The “Oprah effect” was no surprise to the scientific community. Even before Oprah went on her VLCD, a definitive study of her diet had been published. Five hundred patients on Optifast began at an average of 50 percent over their “ideal” weight. More than half of these patients dropped out before treatment was complete. The rest, like Oprah, lost a great deal of weight—an average of 84 percent of their excess weight. An excellent result. Over the next thirty months, the patients, like Oprah, regained an average of about 80 percent. In another follow-up of VLCD, only 3 percent of the patients were considered successes after five years. In yet another study of VLCDs, 121 patients were followed for years after they lost 60 pounds on average. Half were back at their old weight after three years, 90 percent after nine years. Only 5 percent remained at their reduced weight. The best result I can find is a study in which 13 percent of subjects remained thin after three years.

8

No other diet has been shown to work in the long run. There are about a dozen well-executed long-term studies involving thousands of dieters, and all of them show basically the same dismal result: Most people gain almost all their weight back in four to five years, with perhaps 10 percent remaining thin. The longer the follow-up, the worse the outcome. The trajectory points to complete failure after enough time elapses.

9

More telling than what is published is what is not published. There has been dead silence from the commercial programs. They have long-term weight figures on tens of thousands of their clients, but they have kept their findings secret. It doesn’t take a Sherlock Holmes to figure out why.

A few diet experts take the view that enough is enough: Dieting is a cruel hoax, and it is time for Congress to intervene. Many sit glumly on the fence, perhaps awaiting the day of reckoning. But some respected experts call for new and more innovative diets with far more attention paid to maintenance. Drs. Kelly Brownell and Tom Wadden, two leading obesity researchers, have called for a national obesity campaign with the goal of a ten-pound loss by all overweight Americans.

10

These optimists have one plausible argument: Almost all the long-term failures are

patients

—obese people who go to hospital clinics. These may be the most hopeless cases, the terminally fat. Maybe diets will work better on the slightly overweight, the people who don’t need to go to clinics, the people who have not repeatedly tried and failed.

I doubt it. Workplace and home-correspondence interventions have fared just as poorly as hospital clinics.

11

Maybe someone will discover a way to screen overweight people so that only the ones likely to succeed will be accepted for dieting programs. Maybe someone will have that new insight into maintenance that has thus far eluded everyone. But in the meantime, the clearest fact about dieting is that after years of research, after tens of millions of dieters, after tens of billions of dollars,

no one has found a diet that keeps the weight off in any but a small fraction of dieters

.

12

Yo-yo Dieting

Rats permanently change the way they deal with food after they have been starved once. After they regain the weight, their metabolism slows. They like fatty foods more. They accumulate larger fat deposits. The more cycles of famine and feast, the better they get at storing energy. They may even rebound from starvation to a higher weight than ever before once food is abundant again.

13

It looks as if people do the same thing. After dieting, people radically change the way they deal with food. Dieters become intensely preoccupied with food, thinking about it all day long, even dreaming about it. The body changes, hoarding energy. Normal activities—sitting and exercising—use up fewer calories in formerly obese women who have slimmed down than in matched controls who have never dieted. Even sleeping burns 10 percent fewer calories in the onetime obese. Less energy is given off in heat. Lethargy, a real energy saver, is common. Buttercream frosting tastes better than it used to. It may even take fewer calories for a dieter to put on a pound than for a normal person. So a sizable number of patients don’t simply relapse, but wind up heavier than they were in the first place.

14