What You Can Change . . . And What You Can't*: The Complete Guide to Successful Self-Improvement (36 page)

Authors: Martin E. Seligman

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness

When Vaillant compared the men who became abstinent with the men who died or remained alcoholic, he found four natural healing factors among those who recovered. First, the abstinent found a substitute dependency to sustain themselves: candy binges, compulsive eating, Librium, prayer and meditation, chain smoking, work, or a hobby. Second, the abstinent men were threatened with painful and disastrous medical consequences: Hemorrhaging, a fractured hip, seizures, and ghastly stomach problems all brought these men face-to-face with physical destruction (painless liver disease was not enough to drive the point home). Third, the men found a source of increased hope: Religious conversion and Alcoholics Anonymous (of which more in a moment) were typical. Finally, the men often found new love relationships, un-scarred by the guilt and the devastation they had already inflicted on their wives. The more of these four healing factors the men were able to incorporate, the better their chances.

It is against this background of a natural healing process that formal treatment must be compared. Sadly, formal treatments work only marginally better than the natural rate of recovery.

Your first impulse, if you have the means, is probably to enter one of the many elaborate inpatient medical-treatment units for alcoholics. These programs are expensive and usually involve a team of helpers. The best ones offer a wide range of services: drying out

(detoxification)

, counseling, behavior therapy, medical treatment for complications, aversion therapy, a comfortable setting, and AA-type groups. You can have all or some of these. Long-term outcome sometimes seems quite good: For example, one unit points with pride to a recent ten-year follow-up of two hundred former patients. Sixty-one percent were “completely” or “stably” remitted.

16

But the patients from this study were not from skid row—they were socially stable, and so could be expected to have roughly this good an outcome anyway. To determine if such programs do any better than natural recovery, a matched control group is required. This study lacked one, and, indeed, controlled-outcome studies of inpatient units are rare. The patients are usually paying customers, they don’t want to be randomly put into a control group, and they will go elsewhere for treatment if so assigned.

However, there have been some attempts to do controlled studies. A particularly dramatic one was done in London fifteen years ago. One hundred married male alcoholics were randomly given either of two treatments. The first treatment was elaborate: a year of counseling and social work, an introduction to AA, aversion therapy with drugs, drugs to alleviate withdrawal, as well as free access to inpatient medical treatment. The second treatment was merely one session of advice, involving the drinker, his wife, and a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist told the couple that the husband had alcoholism and that he should abstain from all drinking. Further, he should stay in his job, and the couple should try to stay together. The theme was that recovery “lay in [the couple’s] own hands and could not be taken over by others.” Twelve months later, the two groups looked the same: About 25 percent from each group were doing better.

17

George Vaillant found the same result when he compared his own program of intensive clinic treatment at the Cambridge (Massachusetts) Hospital to no treatment. His one hundred patients dried out, received medical and psychiatric consultation, halfway housing, an alcohol-education program, and twenty-four-hour walk-in counseling for themselves and their relatives. Two years later, one-third were improved and two-thirds were doing poorly. Vaillant pooled four more similar treatment studies and had roughly the same results: one-third improved, two-thirds doing poorly. Then he compared all these treatment outcomes to three pooled no-treatment studies. With no treatment, one-third improved and two-thirds did poorly.

18

One study of 227 union workers newly identified as alcoholic contradicts these results. The workers were randomly assigned to either inpatient hospital treatment, or compulsory attendance at AA for a year without hospitalization (or they could choose no treatment). The hospital treatment, which lasted about three weeks, included drying out and AA meetings, and was aimed toward abstinence; afterward, these workers were required to attend AA three times a week for a year and to be sober at work. The compulsory AA group had the same constraints, but without hospitalization. Two years later, the hospitalization group was doing much better than the other two groups: It had twice as many abstainers (37 percent versus 17 and 16 percent), almost twice as many men who were never drunk, and only half as many who needed to be hospitalized again.

19

Putting all this information together, I can recommend inpatient treatment,

but only marginally

. It is expensive, and there is only one decent study showing that it improves on the natural course of recovery; many studies, admittedly of lesser quality, contradict that study.

As for outpatient psychotherapy, there is no evidence that any form of talking therapy—not psychoanalysis, not supportive therapy, not cognitive therapy—can get you to give up alcohol. There has been only one small-scale study of behavior therapy. In it, alcoholics learned skills of how to control their drinking. The study had promising results, but little follow-up of this treatment has taken place.

20

Once abstinence has taken hold, however, talking therapy might help ease the difficult adjustment back into sobriety, responsible family life, and steady employment. Overall, recovery from alcohol abuse, unlike recovery from a compound fracture, does not depend centrally on what kind of inpatient or outpatient treatment you get, or whether you get any treatment at all.

21

With regard to medications, the most widely used drug is Antabuse (disulflram). Antabuse and alcohol don’t mix: When an alcoholic takes a dose of Antabuse and then drinks alcohol, he becomes horribly nauseated and short of breath. This discourages alcohol drinking; but the alcoholic can always decide to eliminate Antabuse rather than alcohol. To avoid this, Antabuse is surgically implanted under the skin. In controlled studies, however, there is no difference in later drinking between alcoholics who have implanted Antabuse or a placebo. Both groups continue heavy drinking when the implantation ends.

22

The use of Antabuse is but one in the larger portfolio of treatments that aim to produce an aversion to alcohol. In electrical aversion, shock is paired with taking a drink in the hope of making the taste of alcohol aversive; this treatment does not seem to work. In chemical aversion, drugs that make alcoholics sick to their stomach are paired with the taste of alcohol. There is better theoretical rationale for this move (recall the potency of the

sauce béarnaise

effect discussed in

chapter 6

, on phobias). Over thirty thousand alcoholics have received such treatments, but without clear effect—the treated groups do about as well as matched controls would be expected to do. Astonishingly, there has been only one study with random assignment to aversion or control. Overall, then, I cannot recommend aversion therapy for alcoholism. There is simply no scientifically worthy evidence that aversion treatment improves on the natural course of recovery.

23

Naltrexone provides new hope for the successful medication of alcoholics. Joseph Volpicelli, an addiction researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, proposed that alcohol drinking stimulates the body’s opiate system and so causes a high. By blocking the brain’s opiate system chemically, the high should be blocked. In a twelve-week study of seventy male alcoholics, half got naltrexone (an opioid blocker) and half got a placebo. Fifty-four percent of the placebo-treated men relapsed, but only 23 percent of the naltrexone-treated men did. Most of the men had at least one drink during the study; the placebo-treated men went on to binge, but most of the naltrexone-treated men stopped after one drink—just what you’d expect if naltrexone had indeed blocked the high. A second study, at Yale, has replicated these effects. Caution is in order because of the lack of long-term follow-up, but this is the most promising development to date in the otherwise fruitless history of medication for alcoholics.

24

T

HE SINGLE

most frustrating question is whether Alcoholics Anonymous and the self-help groups that have spun off from it work. Alcoholics Anonymous cannot be evaluated with any certainty for several reasons. First, AA cannot be scientifically compared to the “natural course of recovery,” my criterion for all the comparisons above, because the group itself is such a ubiquitous part of the natural course of recovery in America. Try to create a control group of alcoholics whose members do not already go to AA. When you do, you will find that they are usually less severely alcoholic than those who enter AA, and thus a useless control. Second, AA does not welcome scientific scrutiny. It promises anonymity to its members and inculcates loyalty to the group—two conditions that make long-term follow-up difficult and disinterested self-reporting unusual. AA bears more resemblance to a religious sect than to a treatment, a fact that is not irrelevant to its success. Third, the people who stay in AA and attend thousands of meetings tend to be the people who stay sober. This does not necessarily mean that AA is the cause. The causal arrow may go the opposite way: Drunkenness causes people to slink away in guilt, and being able to remain sober allows people to stay. Finally, AA is a sacred cow. Criticism of it is rare, and testimonial praise is almost universal. The organization has been known to go after its most trenchant critics as if they were heretics, and so criticism, even in the scientific literature, is timid.

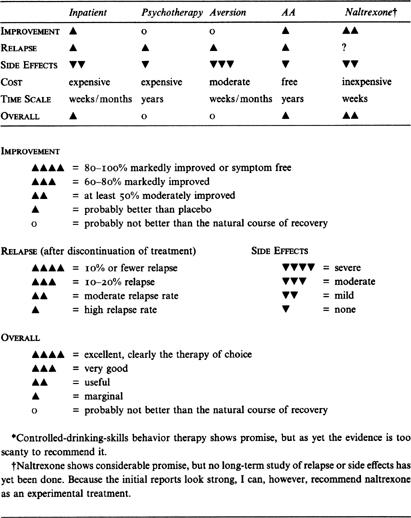

The Right Treatment

ALCOHOLISM SUMMARY TABLE

*

Given this minefield, I will hazard an evaluation anyway. My best guess is that AA is only marginally effective overall, but that it may be quite effective for certain subgroups of alcoholics.

I start with the sad fact that there has not been a single, sound, controlled study of AA. This is unfortunate because AA is the most widespread treatment for alcoholism, and current practice among clinicians, ministers, and family doctors is to send most of their alcoholic clients directly to AA. Advocates publish glowing numbers from uncontrolled studies, but their methodology is so flawed that I am forced to dismiss them.

George Vaillant’s inner-city men provide a sample—with no control group—followed for a very long time. Among the men who were ever abstinent and the 20 percent who became securely abstinent, more than one-third rated AA as “important.” Indeed, AA was second only to “willpower” on this score. In another of his studies, Vaillant followed a clinic sample for eight years, and 35 percent became stably abstinent: Of these, two-thirds had become regular AA attenders. I cannot tell which causes which, but it is an often-repeated finding that of the one-third of alcoholics who have a good long-term outcome, many participate religiously in AA, attending hundreds of meetings a year.

25

AA is not for everyone. It is spiritual, even outright religious, and so repels the secular-minded. It demands group adherence, and so repels the nonconformist. It is confessional, and so repels those with a strong sense of privacy. Its goal is total abstinence, not a return to social drinking. It holds alcoholism to be a disease, not a vice or a frailty. One or more of these premises are unacceptable to many alcoholics, and these people will probably drop out. For those who remain, however, my best guess is that many of them

do

benefit. It would be a mistake to be formulaic about who will find AA congenial. All sorts of unlikely types show up and stay—poets and atheists and loners. AA changes the character of some of those who stick with it. After all, it fills two of Vaillant’s four criteria for bolstering recovery: It provides a substitute dependency, and it is a source of hope.

Total Abstinence

One of my closest friends, Paul Thomas, is a bartender. Paul is nothing if not fanatical. When he took up bridge, he became a Life Master in under two years. When he took up golf, he became a scratch golfer in a summer. When he fathered a Down’s syndrome child, he became president of the Philadelphia chapter for helping Down’s children. When he took up drinking, he drank for ten solid years. He has not touched a drop in the last fifteen years. When asked how he does it, he says he doesn’t need reminders of hitting bottom because he sees them every day among his customers.