Unlikely Warrior (29 page)

Authors: Georg Rauch

It must have been February when I sat up in bed for the first time and let my legs dangle over the side. I immediately lost consciousness. After a few more attempts, I finally succeeded, and looking out from my third-floor window I was able to see the snow-covered roofs of the destroyed city. Another patient pointed out to me the bombed-out factories where they allegedly took the bodies of those who died in the hospital and walled them up. No records were kept of these deaths, no lists of names.

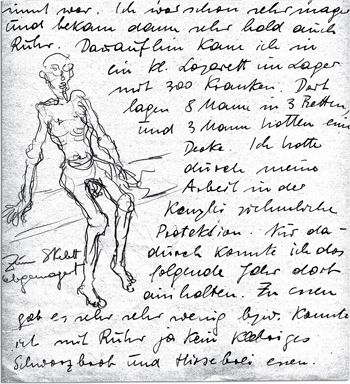

My body was now just skin and bones, and my muscles had disappeared completely. Making a circle with the thumb and forefinger on one hand, I could run it all the way up and down the other arm. Skin detached itself everywhere in large dry scales. I also had many painful sores on my back and sides from lying for so long on the hard bed.

* * *

Captain Pushkin appeared on one of the first days of March, bringing me two red apples. “Well, it looks as though you are back among the living. Dr. Petrovsksy thinks the worst is behind you now, and you are on the way to recovery. Tomorrow you will be transferred to a camp infirmary near the woods, on the outskirts of the city. The air is better there, and pretty soon you’ll be able to lie outside. How does that sound to you?”

“It sounds wonderful,” I said. “Anything that will get me back up on my feet is fine with me!”

The woods hospital was a barracks surrounded by trees and meadows, similar to the one in the bunker camp. A few steps away, behind a wire fence, was the part of the POW camp from which columns of prisoners went out daily to work in the nearby dairy farms, nurseries, and forests.

I was placed in a room with twelve others. At first my fellow patients gave me the usual cold shoulder when they noticed my preferential treatment. Nobody asked why I was receiving all the special privileges. But I had learned by now how to thaw the most stubborn blocks of ice with presents of food. In this way a pleasant atmosphere soon reigned in the room, and that was more important to me now, since I hardly slept anymore during the day. Contact with the other prisoners helped a great deal to pass the time.

Each of my roommates had an interesting story to tell. I asked unusual questions about their professions, and I was a good listener. In this way I found out, from a delicatessen store owner, that one can keep large wheels of cheese freshly stored if they are wrapped from time to time in towels dipped in vinegar. Another told me how to look for and prepare the different kinds of wood required to build a cuckoo clock.

One morning an orderly appeared and said, “They just put a countryman of yours in the next room, a Viennese.”

“From Vienna? What’s wrong with him?” I asked.

“Just a broken arm. It was a woodcutting accident.”

“Well, give him my regards,” I said. “Maybe he can visit me soon.”

He came the next morning, an educated-looking man in his fifties, wearing a white cotton shirt with the corresponding regulation long white underwear.

“Grüss Gott,”

he said, with a light Viennese accent. “My name is Oskar Fuchs.” He stretched out his hand in greeting.

“Georg Rauch. It’s nice to see someone from back home. How are you doing?”

“Oh, it’s not much. The bone was just splintered,” he answered, pointing to his arm. “It shouldn’t take long. And how about you? Have you been here a while?”

After half an hour’s conversation we knew the general outlines of each other’s life histories, and his contained quite a surprise for me. He had been a cello professor at the conservatory in Vienna. As a young music student he had come into Vienna daily by train from the suburbs. In the evenings he often played chamber music with friends, and it was in this way that he had met my mother, who was twenty years old at the time and studying piano.

My grandfather was a very well-to-do man and a great music lover. It was not unusual for the musical evenings at his home to include up to twenty instruments, and hardly a mealtime went by without guests, often from other countries. Many of the young musicians who were “at home” in my grandparents’ house went on to become conductors of the Vienna Philharmonic or famous soloists. Oskar told me that he often stayed overnight at my mother’s when it became too late for him to catch the last train home. What an incredible coincidence!

Oskar was in much better physical condition than I was, since he had never been forced to take part in any of the long starvation marches, nor had he been in camps with outbreaks of dysentery and other similar epidemics.

He spent a great deal of time with me during the following days, and when a bed was vacated in my room, I asked the head doctor for permission to move Oskar in.

Although he must have noticed my unusual status very quickly, during the first few days Oskar said nothing concerning my special care, books, and vitamin pills. Once when I ordered an extra bowl of soup and gave it to him, he finally posed the question that had never been asked before. “How is it that you can get food on demand, and all the other things?”

I couldn’t tell him the truth, so I gave him the answer I had already prepared much earlier. “Before I became ill, I worked as a draftsman for a friendly Russian captain. Evidently he took a shine to me, and when I got sick he arranged all of this. Now and then he comes to visit. He’s married to a Viennese Jew.”

“Not bad. One just has to be lucky. ‘A Viennese doesn’t go under.’”

“Without him I would have gone under, underground, a long time ago,” I said.

A little later Oskar asked, “Is it possible for you to order butter or oil?”

“Why? There’s some butter in the can in my sack hanging there.”

“Your skin is so dry. I could massage it with the butter.”

With this began a daily routine that continued for the following weeks and demonstrated to me what a disciplined and caring person Oskar was. Every day he spent at least an hour systematically massaging one part of my body after the other with butter. He spent another hour bending my joints and having me press my arms and feet against the palms of his hands. I soon felt my skin becoming softer and more elastic, and sitting also became less of an effort.

Self-portrait. Reduced to a skeleton in the camps.

Next he made plans for my diet. He told me to order two loaves of bread and extra butter. When they arrived he disappeared with them. He also took the wine bottle half full of vodka that I had in my cloth bag. Weeks earlier someone had come up with the crazy idea that two tablespoons of vodka per day would be good for my digestion and would also stimulate my appetite. I accepted the vodka, but when the nurse left I always poured it out of the cup into my bottle. The only time I had tried it, it burned my tongue and I had been unable to swallow it.

When Oskar returned a couple of hours later, he brought two plates, one with lightly browned fresh fish, sliced new potatoes, and a fresh green salad. The second was filled with beautiful red strawberries, partially covered with cream.

When I saw all this, I thought I had to be hallucinating. I, the poor fellow with no appetite, felt my mouth watering for the first time in months.

“Where did you get all this?” I asked.

“I traded the bread and butter at the fence with workers coming home. If someone has had nothing but fish all day long, he dreams of bread and butter. The same for those coming from the nursery and dairy farm. All of them steal something and smuggle it into camp. I found out that there’s always heavy trading every evening at the fence.”

“But who prepared it so beautifully?”

“Oh, that overstuffed cook will do anything for a little extra vodka.” Oskar laughed.

Everyone in my room ate well. Thanks to Oskar, I ate particularly well. A large part of Oskar’s day was occupied with my exercises and obtaining special foods. Often when I ordered shamelessly large amounts of food, I would think I had surely overstepped my limits, but nothing happened. Promptly, and without further ado, I received whatever I had requested.

By mid-April I had made such progress that I was able to walk up and down the room, and I began visiting the large barrel out in the hall a few times a day. Two men could sit on it at one time, and all that were able to get out of bed used this primitive toilet facility. Quarrels often broke out if the barrel was occupied and someone was in a particular hurry. After so many months, with no reason or occasion for laughter, it struck me as really funny to see my fellow skeletons, their white pants halfway down, fighting to decide who would sit on the barrel first. On one such occasion the half-full barrel was tipped over, and the skinny squabblers lay exhausted in the brew.

Once again, the world was beginning to bloom, and I obtained permission to lie outside on a mattress in the shade. Supported by Oskar, I would walk back and forth for several minutes a few times per day. I began to enjoy ever more fully the reality that I was still alive.

Spring also had its less pleasant aspects, however. When it rained the water came through the roof, and the orderlies pushed our beds into a chaotic arrangement so that we wouldn’t get wet. The flies also returned with the warmer weather and crawled around on us endlessly. After a while we gave up shooing them away, because they were everywhere, by the hundreds.

Bedbugs also fell down on us from the ceiling to suck our blood during the night. At dawn they crept past our beds on their way back up the walls to the ceiling, where they disappeared into the cracks for their hard-earned rest. When they passed my bed within reach on their way up the wall, I squashed them, trying to produce an interesting design at the same time.

One afternoon, as I was lying under a tree in the meadow, Captain Pushkin came and sat down beside me.

“How are you feeling?” he asked.

“I’m doing much better, thanks to my compatriot, Oskar Fuchs. He has been massaging me with such patience and persistence. I’ll miss him when he is well and has to go back to work.” I imagined I was being subtle.

“Herr Fuchs has been well enough to return to work for some time now. We know that. But don’t worry, he’ll stay.”

“Hmmm,” I murmured, reddening a little from embarrassment.

“We also know all that you have been ordering from the kitchen … and receiving.”

I smiled somewhat guiltily. The captain also smiled, so everything seemed to be all right.

“Do you remember the task we assigned you?”

“I remember,” I answered.

“We haven’t pressed you during the past months, because you were in such poor physical condition. Now you should start thinking about your assignment again.”

“I’ll do that,” I replied.

After a few more polite phrases the captain made his departure. I knew I definitely wouldn’t be alive at that moment if I had decided differently in Captain Pushkin’s office back in November. But now it was all too clear that the day of reckoning had finally arrived. I would now be obliged to deliver, to pay for all those good things I had managed to squeeze out of them since I had agreed to spy for Russia.

While hoping to figure out a way to evade my mission, I began analyzing the various individuals in my sickroom. One of them was a Romanian, another a Pole. They could be omitted as suspect Nazis right from the beginning. Foreigners hadn’t been party members; the Nazi party had been purely a German affair.

Another prisoner, a German, lay near death and probably wouldn’t survive the following day. The man in the bed across the way from me was a farmer who had a little farm high up in the Bavarian Mountains near the Austrian border. I didn’t believe he could be considered as a party member, especially remembering the stories about how he and his brother had smeared their faces with black shoe polish and smuggled bicycle parts across the border into Austria before the Anschluss.

The fellow in the bed next to me owned a delicatessen and had told us not too long ago of all the tricks he had employed in trying to stay out of the army, including some sort of injections that faked a liver problem. He surely wasn’t a Nazi. The boy in the bed to the right of the farmer had just turned seventeen, so he wasn’t a likely candidate either.

In the next row of beds lay an accountant who had worked at a

Lebkuchen

factory in Nuremberg. He was a father of five who had entertained us enormously with his stories of trading sugar stolen from the factory for butter, potatoes, and bacon that the farmers had in abundance. Also not your typical party member.

Farther down the row was a seriously ill man in his midthirties. He had only one arm, and his face was twisted and contorted from the many shell splinters that had entered when he was hit. He had hardly spoken since his arrival, but I seemed to recall that he had been a dentist before the war. “I’ll simply leave him out,” I decided. “He’s already suffered enough, shot up the way he is, and there’s little enough chance that he’ll still make it home anyway.”

The patient in the far corner of the room was an engineer. He was somewhat older than the rest and obviously in the advanced stages of lung tuberculosis—coughing, spitting, and still smoking. Going by his general type, he might have been a Nazi, but it was very unlikely that he would survive the coming week.