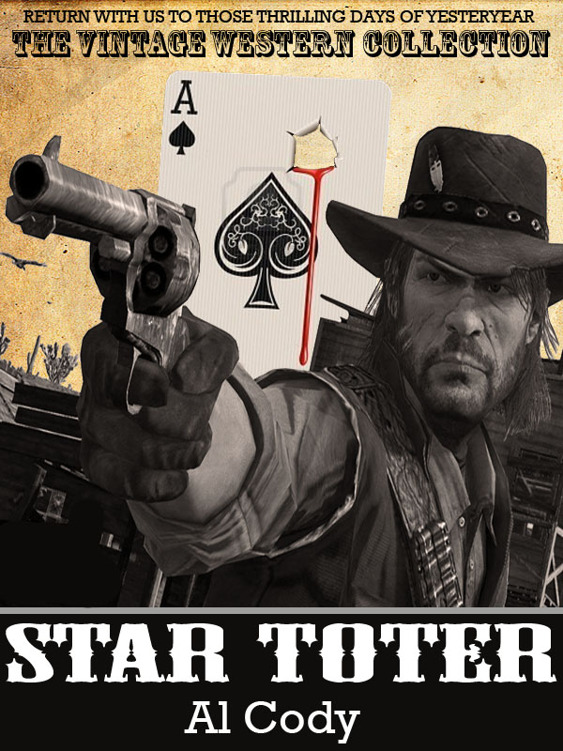

Star Toter

by Al Cody

Scanned and Proofed by RyokoWerx

Fletcher Bannon was drowning his sorrow in Kirke's dingy saloon when Locke returned to Highpoint. Bannon had been immersing his woes at the same table when Locke had last seen him seven years before.

For a moment, Locke stood unnoticed just inside the door—a tall man, who at first glance seemed too thin for his height, too finely drawn to a whipcord hardness. His skin was weathered by sun and wind, and his eyes caught the glint of light like the polished barrel of the forty-fives which swung at either hip. A sprinkling of gray was showing at the edges of his dark hair, and his mouth looked as though laughter had long been foreign to it.

The man he looked upon was ageless. Time had placed no lines in his face, no fat on his comfortably fleshed frame. It had failed even to glaze his eyes, though beer had puffed and curiously tinted the skin. His sandy hair was thick, unchanging in color. No one would have suspected that Dr. Fletcher Bannon had been in his thirties the day he had first set foot in Highpoint, or that that day had been nearly three decades forgotten.

Bannon lifted his head, like a fox aware of an alien odor. He turned it, blinked, then came lightly to his feet, hand outstretched. "Orin Locke, as I'm a taster of the rye!" he exclaimed. "Man, it's good to see you again!"

Locke's frosty eyes warmed. For a moment the two clasped hands silently; then Locke sank into the chair which Bannon kicked toward him. "You're like Ben Bolt, Fletcher," he said finally. "There never is any change in you."

"No," Bannon agreed, "I don't change. I'm still the sot I was when you went away, Orin, still a disgrace to the community and my profession. But you, now—you return to the Wild Buttes with a reputation."

"And little else." Locke shrugged. "No good in that."

"They say that you're the fastest man with a gun in a land of fast men, the coldest-hearted marshal that ever tamed a town. But if that be so, which I would not doubt, it has done things to you." Bannon studied him closely, shaking his head. "You're less than half my age, but you look older than I do."

"And I feel that way," Locke agreed. "I saw a funeral procession as I came into town. That's unusual."

"What's so unusual about it?"

"Those usually come

after

I hit town." The words were bitter.

"There are plenty of funerals these days," Bannon commented sadly. "Since gold was found right under our noses, where the town had walked for a quarter of a century above it, Highpoint has changed. That funeral was for the sheriff, Burnt Cassell."

"Cassell, you say?" Locke's eyes clouded. "I knew him in Dodge; he was my deputy when I wore the star there."

"So I had heard. He was a good man, a good star toter—till they drygulched him." Bannon's eyes were inquiring, kindly. "You've come home, Orin?"

"Home?

Quien sabe

? The wind blows."

"And it carries odors. The town could use a man of your ability, now that Cassell's gone; a man with your reputation and your guns."

Locke shook his head. "I'm through with that sort of thing, and sick to the soul of the smell of powdersmoke. All I ask is peace. I shall go out to the Wagon Wheel—at least for a look. I want to forget that there ever was such a thing as an officer's star."

Understanding pity clouded Bannon's eyes. "Do you think they'll let you?" he countered. "A man can dream, Orin, but waking always follows. And are you sure that you will find peace on the Wagon Wheel?"

"I long ago learned that you can never be sure of anything," Locke returned grimly. "Is it that bad?"

"Maybe.

Quien sabe

?"

On that note Locke arose. Outside again, he stood, his eyes ranging the town. Highpoint had changed; a gold rush did that to a town. And the change was not for the better.

Highpoint was set upon a hill. There were loftier mountains to the north, and more off south, sprinkled with evergreens. Gaunt canyons cut between the hills. The grasslands, more gentle of slope, lay east and west.

Locke found his horse and left the town behind, riding out through a gap, taking a remembered road. The Wagon Wheel lay to the west.

A hunger to see familiar faces had brought him home; also a hope that after all these years he might be made welcome. He rode slowly, hearing the murmur of Queasy Creek, before it swung south and east to lose itself in a maze of hills.

He had covered half the distance to the Wagon Wheel when his eye caught the light ahead. Here a road crossed an open meadow, but he was still under the shadows of cottonwoods which crowded a spring. A similar grove was ahead, and in their soft dusk a cigarette glowed.

Locke stopped. Presently he made out two horses and two riders. Voices came in whispers. It was undoubtedly a lovers' tryst.

He was about to ride ahead when the cigarette made an arc like the flight of a firefly. Then the man who had discarded it raised his voice, saying good night and riding on up the road, the way Locke was heading.

Recognizing the voice, Locke sat rigid. There had been no change in seven years. It was still the same assertive voice that he had come to hate, and it belonged to his younger brother Ray.

Apparently the voice, raised in a careless leavetaking, had rasped on the nerves of the girl as well. Her horse burst from under the trees and headed for the road across the open meadow, running as from a sudden wild kick of spurred boots. Locke had time to see flying hair, pale gold in the light of the moon. A slender figure leaned forward in the saddle, her face white and set. The next instant brought catastrophe.

This was not so high as Highpoint. The road to the west had been dipping ever since Locke had left town. The meadow was dotted with tiny hummocks of dirt, some fresh—the work of pocket gophers.

One tunnel had undermined the meadow, and the cayuse's hoof had broken through, down into the tunnel. Ordinarily such a break would have caused no particular damage, but since the horse was running hard, the wrench was disastrous. It threw the pony, which sprawled wildly, and the girl was tossed from the saddle to fall heavily.

Snorting, the cayuse got to its feet, unhurt. But the girl lay where she had been flung. She was still motionless when Locke reached her.

As he stooped, her eyes opened, wide with momentary terror. She stared, and for an instant he thought she was going to scream. His own voice was quick, reassuring. "Take it easy, ma'am. You'll be all right."

She had good stuff in her. The fright passed, and she struggled to sit up. Then, becoming aware of the disarray of her dress across shapely ankles, color drove the whiteness from her cheeks, and she reached to arrange the dress more decorously. Her eyes never left his face.

"What happened?" she asked. "It was all so quick—"

"It was that," Locke agreed. "Your pony put his foot in a gopher hole and took a tumble—you likewise. I hope you're not hurt?"

She shook her head, still watching him. "I'm all right, I think. But you—haven't I seen you somewhere before?"

Locke shook his head. "I wouldn't think so, ma'am."

"But—now I have it! You look like Ray Locke. That's it!"

"Might be," Locke conceded, his face expressionless, "since he's my brother."

Her eyes widened with quick interest. "His brother? Then you're the marshal? Orin Locke?"

"I'm Orin Locke, yes."

She looked at him for a moment longer, frankly curious. "I've never seen a real town tamer before," she said.

"Some of them look almost human," Locke assured her. "Don't judge them all by me."

She colored, as if at a rebuke. "But I wasn't," she protested. "What I mean is, Mr. Locke, I think you're very good-looking, distinguished and all—"

He was no ladies' man, and no one had ever accused him of it. But seeing her confusion, he took pity on her. "You've got the advantage of me," he reminded. "You know who I am."

"Oh, yes, of course. I'm from the Three Sevens."

It was Locke's turn to stare. "The Three Sevens?" he repeated. "That's Jeb Landers' spread." He shook his head, remembering. There had been Landers' girl—what was her name, Virginia? She'd been a leggy kid, running to freckles, when he'd seen her last.

"You don't mean to tell me you're Ginny Landers?" he ended somewhat lamely.

She shook her head, coloring again in confusion. "No. I forgot that you wouldn't know. My father has had the Three Sevens for years now. I'm Reta Cable."

Locke doffed his big hat gravely.

"I'm right pleased to know you, Miss Cable," he said. She started to get quickly to her feet and all but fell, clutching at him with a little moan.

"Oh-oh, my foot!" she wailed. "It hurts!"

Her face had gone bloodless from the pain, so that he knew it was no trick. He steadied her, and she sat down again. Locke examined her left foot.

"No bones broken," he pronounced, while she watched wide-eyed. "But it's swelling. You must have wrenched it. Best thing will be to get home and take care of it. Here; I'll help you."

He caught her horse, now grazing contentedly near his own, brought it back and helped her to her feet. He solved the problem of getting into the saddle by picking her up in his arms, lifting her, lightly as if she had been a child, and depositing her in it.

"One lucky thing: it's not far to your place," he said. "I'll go along and see that you get there all right."

"That's very kind of you, though hardly necessary, Mr. Locke," she said. "I can ride all right."

"But you wouldn't cheat me out of a moonlight ride with a fair lady?" he protested.

She looked at him quickly, struck more by his tone than by the words. Such phrasing did not suggest the cowboy or the two-gun marshal of a tough town.

"Of course I'll be glad to have you," she agreed. "Ray usually sees me home—but tonight he seemed to have other things on his mind."

"Mebby word had reached him that I was coining," Locke returned.

The moonlight was still bright when Locke approached the Wagon Wheel.

Lights still showed from the windows of two or three rooms in the sprawling house. A man sat huddled in a big rocking chair on the wide porch; the faint creak of the chair was audible in the windless night. Voices came from the bunk house not far away. It was a warm night, this night of full moon, and would be rather hot and stuffy inside. Consequently, no one was in a hurry to get to bed.

He looked again at the figure on the porch. The moonlight reached just to its edge, so that the chair and the man were in shadow. But from what he had heard, he was confident that this would be Ray Locke, Sr., his father; a strong man until he had been stricken with heart trouble, which apparently had grown progressively worse with the years. Locke had heard rumors that now he was all but helpless; that news had made him decide to return.

He sat on his horse, looking around, then swung down from the saddle. As he started forward, a figure emerged from the shadows near the barn and moved to intercept him, as though he had been on watch. "So you're back!" Ray Locke said.

It was more a challenge than a greeting. For a moment they confronted each other, standing equally tall. There was no welcome in Ray's voice or eyes. None of the old animosity was dead.

"I'm back," Locke agreed, and tried to make his voice sound friendly. "I heard about Pa not being well."

"He's over there," Ray said uncompromisingly, "in that chair."

"So I see." Locke held his rising temper in leash with an effort. "How was he hurt?"

"He wasn't hurt," Ray retorted. "He's blind."

Locke felt suddenly deflated by the flat brutality of the words. His father was a proud, hard man who had never been able to adjust or make compromises. To be unable to see or get around or take part in the business of living would be particularly hard for a man who had always been a driver.

"What are the chances of his seeing again?" he asked. "How about an operation?"

"Doc Emery says there's no chance at all. It's one of those things."

Emery! That, too, had an alien sound on the Wagon Wheel. Doc Emery had come to Highpoint about a year before Orin's departure. Probably he was a good enough medico, but Emery had always impressed Locke as a man obsessed with a sense of his own importance; and that, all too often, was a mark of ignorance or inability.

Fletcher Bannon had always been called in the old days when a doctor was needed, at least up to the time when Ray had been thrown from a horse and brought home unconscious. One of the cowboys had summoned Emery, and Emery had brought Ray out of that all right; from then on, apparently, he had been the family medico.

"That's tough," Locke said soberly, "mighty tough."

"Sure it's tough," Ray agreed. "But you don't want to make it any harder for him, do you? He's pretty deaf, too. I think I can manage so that he won't hear about your coming back. That'd be a lot better."

There was no need to ask questions. It was clear that his father hadn't changed.