Unlikely Warrior (25 page)

Authors: Georg Rauch

“I think it’s about time to make for the bushes again, don’t you?” I said to the Berliner. “Are you coming along?”

“You’re reading my thoughts. And I wouldn’t mind at all biting into some of those plums and all that other fruit.”

When there didn’t seem to be any Russians in view, we simply wandered off into the high cornstalks. In the adjoining field we found a watermelon, ripped off a few ears of corn, and made ourselves comfortable in a pile of hay, not even caring to consider what might happen later.

I awakened the next morning to the sound of voices. Carefully I moved to the edge of the field, bent a few high stalks apart, and found myself facing only ten meters away a small blond boy, not more than six years old. He was dressed in a miniature Russian uniform, his gray military shirt with stand-up collar pulled together by a wide leather military belt. A little uniform cap with a red star was perched on his yellow curls.

Without a moment’s hesitation, he began walking purposefully toward me while I nervously considered in what manner, preferably as silently as possible, I could kill him. In order to survive myself, I had to get him out of the way. I had to gain time until my foot was healed or else I would never be able to keep up with the column without falling back and being shot.

As the child came up to me and took hold of my jacket with his pudgy hand, I looked down at him … and did nothing at all. He began pulling me, and I followed without resisting. The Berliner, who had been a few yards farther back, remained in the field. My captor led me across autumn fields, past the working women whose voices I had heard, and past farmhouses in front of which men and women stood, calling out admiring comments to the proud youngster. Finally we arrived in the village, where the child handed me over to a few officers at the commandant’s office.

So I was once again in the hands of the Russians, much sooner than planned. They locked me up in the windowless village jail, and around noon they brought a bowl full of food that they permitted me to eat outside, seated in front of the jailhouse door.

A few meters away, in a shady, open space between the adobe houses of the village, a dozen officers sat on benches around a long table. Three or four were women, and all were eating heartily. Cutlery, except for a large, crude knife, was nonexistent. The Russians tore the fried chickens apart by hand, stuffed the flesh into their mouths, and washed it down with wine or vodka. Watching them was fascinating, and this first view of the Russians away from the battlefield or the prisoner columns made a very strong impression on me.

The fried hunks of meat, torn pieces of tomatoes and cucumbers, and half-charcoaled potatoes were dipped into piles of coarse salt on the rustic tabletop. The juice ran over their faces and hands. The chicken bones and the unappealing parts of fruits or vegetables were simply thrown in an arc over their shoulders. Because of the heavy imbibing, the mood grew louder, but finally all were full and most lay down in the grass to rest.

One of the women, who seemed very young to be an officer, came over and examined my heel. She must have noticed me limping as I was brought in. At her order, one of the soldiers took me into a connecting house. The young lady officer was quite attractive, with Slavic features and dark hair. While attending to my foot she asked me, “What city do you come from?”

“From Vienna, in Austria,” I said.

“Waltzes, Strauss, Danube,” she said, smiling. And then all of a sudden she became excited. “Music! Can you fix a broken radio?”

“Of course,” I bragged. “I’m a telegraphist.”

I would have claimed with equal certainty that I could butcher a pig or repair a Venetian mirror. Anything to gain a few hours or days out of the great marching masses. For the moment, I seemed to be the only prisoner in the village, and that also gave me hope for better rations and care.

The young doctor led me to a house on the other side of the street and spoke to an officer. He took me inside and showed me the radio that sat on a table in a glassed-in veranda. It was a Braun portable, exactly the same model I had purchased in Vienna the year before I was drafted. At my request, the officer brought me a screwdriver and pliers. I unscrewed the back cover and peered into the tangle of wires, tubes, and condensers. One of the wires leading to the loudspeaker was loose. To repair it would be a simple matter and take a mere five minutes.

I turned to the officer standing at my shoulder and said solemnly, “I know this type. Given enough time, possibly I could repair it.”

“Karascho,”

he answered.

He arranged for me to be brought a plate of food and a cup of wine, my second meal of the day. This struck me as an unexpectedly friendly gesture, and my hopes rose. Then he sent me back to the town jail for the night.

The next morning a soldier came for me and took me to the doctor. She disinfected my wound and made a new bandage. In her presence I suddenly felt, for the first time in what seemed like ages, that certain male/female feeling. It seemed like a forgotten wonder to me.

A few hours later, after a good breakfast and several appearances of the lady doctor and others, I permitted the radio to emit a loud crackling noise, which was interpreted as a good sign by those present in the next room. The second day I let the radio play music for a few seconds and was immediately rewarded with an especially large plate of food and a cup of wine. That same evening the radio played perfectly. Everyone danced and got tipsy to the program of a Russian military radio station. The doctor brought me two more glasses of wine, referring to it each time as medicine. It was close to midnight before they led me back to the jail.

I gained one more day of good rations for putting the radio back together, but the following day I was loaded into a horse wagon and driven ten kilometers back to the same camp from which I had marched away a week earlier.

The camp was now full to bursting. Twice a day, columns of five hundred to a thousand prisoners marched off to unknown destinations. The third day after my return I was assigned to one of these columns. The landscape was now flat and treeless, and again we received only a few ears of corn for our daily rations. Once or twice a day we were permitted to drink from puddles or ponds.

The guards were very strict and unfriendly, especially following a few incidents. Once a German sprang out of the line toward a well. Bullets brought him down before he ever reached it. During the long nights many also tried to escape and were shot.

I had finally given up on the idea of escape. When my foot was so bad, I hadn’t had any other choice, but by now it had become clear that I would never be able to make it all the way home. For now I was happy to have reached a point where I was no longer being shot at. If I could now come to terms with the fact that I was a prisoner, however long that might take, I might have a good chance of surviving.

I reasoned that if the Russians had intended to shoot us, they could have done that right at the start. If I tried to escape again, with the intention of making it home, I would only turn myself into a living target. Obviously I wouldn’t be able to use any public or private transportation, and at any rate I had only the vaguest idea of what direction to take. Thus I would have to face a thousand barefoot kilometers without warm clothing, trying to survive on stolen food and chance finds of water, and all this with another Russian winter just around the corner.

A month had now passed since my original capture. The nights were becoming noticeably cooler, and more and more often it rained for a few hours. On those occasions we were soon covered with mud, and walking on the sodden track became more difficult. The advantage, however, was that we no longer had all that dust to swallow, and the rain provided additional puddles from which we were sometimes allowed to drink.

My strength began to flag once again, not least of all because of the contaminated water and the diarrhea that followed without fail. More and more of us, above all those with injuries, collapsed and didn’t get up again. The Russians made short work of these. We heard the brief bursts from their machine guns more and more often. I had the feeling we were being urged to more speed than at the beginning. Some of the prisoners toyed with the idea of overcoming the guards. In my opinion, that could only have resulted in a monstrous bloodbath.

We began to realize that if this march didn’t soon come to an end there would be very few survivors. Even those who were still relatively healthy couldn’t endure much longer under the terrible conditions. On the sixth day we saw the silhouettes of watchtowers on the horizon. Until then, I would never have imagined that such a landmark could become a goal toward which I would strive with new hope, summoning my last remaining reserves of energy.

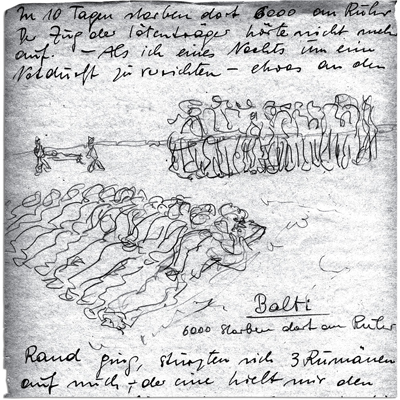

We finally arrived at Balti, an open field fencing in thousands of prisoners with barbed wire. No roof or shelter of any kind was to be seen. Machine-gun emplacements topped the wooden watchtowers. Mounted soldiers patrolled outside, their fingers on their triggers.

Our column was gobbled up into the gigantic mass of prisoners. I stretched out full length on the damp ground and felt relief simply at no longer having to walk. It was the beginning of a new stage, one that didn’t seem to promise anything positive.

During the daytime the sun shone off and on, and the conditions were more or less bearable. We received one loaf of bread a day for twenty men, and its proportioning often led to arguments. When these developed into actual fights, the Russians simply came and took the bread away again. Twice a day we received a ladleful of buckwheat cooked in water. After waiting in the food line for hours, we held out pieces of wood or tin, a mess kit, or, lacking these, our empty hands. Then we gobbled the kasha down with our fingers. Nobody had a spoon.

The nights, however, were ghastly. My thin jacket and pants were no protection at all from the cold, wind, and rain. We had nothing soft or dry to lie on, nothing with which to cover ourselves, no corner into which we could crawl and curl up.

Three methods were developed for getting through the nights. One way was to keep in constant motion, especially important when it rained. We walked on beaten paths, with hundreds of others, in an enormous circle, always in the same tempo as those in front and behind. My eyes became accustomed to the dark, even in the rain, and soon I was familiar with all the obstacles, such as a small ditch or the large root of a bush. With our heads hanging down, half-asleep, we walked behind the others, next to the others. There was no talking.

The second method was to lie down at the end of a long row of prisoners who were lying on their sides, one body pressed spoonlike closely to the next, and hope that someone else would soon move in from behind so that you would be warmed from both sides and protected from the wind. The last man in the row always yelled loudly, making propaganda to enlist the next neighbor. Every half hour another loud call rang out, the signal for everyone to turn simultaneously to his other side. This turn command, a long, drawn-out “

hoo-ruuuck

,” droned throughout the night like an unending dirge.

Finally, there was the third method, the standing groups. Hundreds of men stood motionless, squeezed very tightly together into enormous blocks of humanity. Those on the outer edges also called out, soliciting others to join the block. In such groups you couldn’t fall down, but it also was impossible to get out when you wanted or needed to. I was tempted by the promise of warmth, but the thought of having to stay inside until that entire mass of men dissolved itself at dawn was horrible to me. The standing blocks also stank abominably, since everyone had to answer the calls of nature standing up. I only tried this method once.

Usually I spent the first part of the night in the lying columns, using half a brick for a pillow. The rest of the hours I spent walking in the circle, catching what additional sleep I could during the next day.

One night while I was in the lying group, I heard the command to turn, and when I rolled over I noticed that the man pressed next to me on the left was cold and stiff. I spent the rest of the night sitting, my head on my knees, feeling sorry for myself.

Sleeping methods at Balti, the first POW camp.

The following morning we learned that dysentery had broken out in the camp. Very soon the lines of corpse carriers were unending. For an extra cup of kasha for each body, some of the prisoners carried or dragged the bodies outside the camp and threw them on a pile that was then splashed with petroleum and lit. Our nostrils were constantly filled with the smell of burning flesh. Inside the camp the Russians made their daily rounds, kicking any who were lying on the ground in order to discover the dead and have them carried away.

During one of those endless nights, as I was making my way in the dark to the area that served as latrine, three men jumped me. One held my mouth closed and pressed something sharp against my neck, while the others pulled off my pants and jacket. At dawn I stopped by the kitchen and begged for an old sack to cover my nakedness. Then I volunteered to carry a corpse. Before we threw him on the pile, I stripped off his clothing in order to have it for myself.